In anticipation of the release of Murder on the Orient Express this weekend, Jorge Molina takes a look at a lesser known Agatha Christie adaptation to see how a mystery can introduce its suspects before it even begins.

There are few things that give me more comfort in life than murder mysteries. Clues woven cleverly through a narrative, the slow reveal of hidden motivations, the buildup to a clean and logical resolution. Watching one person inevitably emerge a criminal from a large group of eccentric and enigmatic characters.

There are few things that give me more comfort in life than murder mysteries. Clues woven cleverly through a narrative, the slow reveal of hidden motivations, the buildup to a clean and logical resolution. Watching one person inevitably emerge a criminal from a large group of eccentric and enigmatic characters.

Agatha Christie is still the undeniable queen of the genre. In her novels she perfected the character archetypes for these stories: the charismatic millionaire, the begrudging femme fatale, the quiet foreign girl, the ambitious older lad... to name but a few.

And when her work started to inevitably get cinematic adaptations, with them came a pool of dramatic flair for actors to dive into...

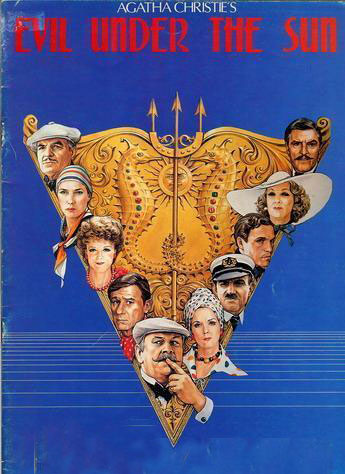

Like most Agatha Christie adaptations, 1982’s Evil Under the Sun has a large ensemble cast, where every character plays a major role in the case. For the audience, as for famed Detective Hercule Poirot (Peter Ustinov), everyone’s a suspect. And, in pure whodunit fashion, the script and the film both find a way to feed us biases against each of them before the first scene even starts.

Evil Under the Sun

Written by: Anthony Shaffer

Based on the novel of the same name by Agatha Christie

[You can read the full script here. I will be talking about these pages and this scene.]

Just like a climactic murder revelation, we need to understand the background of this: there are two important things to note about the way Christie introduces her characters and how the cinematic counterparts adapted that.

Christie was not only a novelist, but also a very successful playwright (her play The Mousetrap has been continuously running in London since 1952). In pure theater tradition, many editions of her novels include a character breakdown before the text, with a brief, sentence-long description.

In a very unusual move, the script for Evil Under the Sun does this as well. This may be a practice that just died with time, although it's unlikely. I’m more inclined to think it’s an homage to Christie’s theater background and book style. In any case, with the introduction of the characters before the movie starts, we at least have a phrase-long expectation of them. We’re starting to get to know them, just like a detective would.

The second element that’s characteristic not solely of Christie but that she certainly mastered, is the way that seemingly throwaway elements like small talk, everyday objects, or coincidental events suddenly become clues once the case has been revealed and one looks back at them. No one ties loose ends better.

And while the movie does plant every relevant clue throughout in an initially inconspicuous way, it also takes the same artifice as the script and places hints somewhere even less viewers are inclined to look. The art and graphics department took the basic idea of this “script prologue” and applied it to its cinematic counterpart in an opening credits sequence.

This opening montage is made up of watercolor drawings of locations inside the island. But once the cast starts to appear, the name of each actor is accompanied with an image that is also a visual clue for their characters: who they are, their intentions, the role they will play.

We don’t know it yet, but [SPOILER ALERT] being in a lounge chair will be the alibi for James Mason’s Odell Gardener, a tennis appointment with Denis Quilley’s Kenneth Marshall is vital to the timeline of the crime, and the big, bright, red hat of Diana Rigg’s Arlena Stuart becomes iconic. These apparently throwaway images, if we looked back at them again after it’s over, would become clues.

Before a character has even said a word in the script, and before we even fade into the first scene in the movie, we already come with small, unconscious preconceived notions and information about the characters we’re about to meet. Anthony Shaffer in the page (and the art department in the screen) managed to step outside the boundaries of the story to play with our expectations of the group of people we’ll be stuck in an island with for the next two hours.

Honestly, Agatha Christie would have probably loved that.