by Tim Brayton

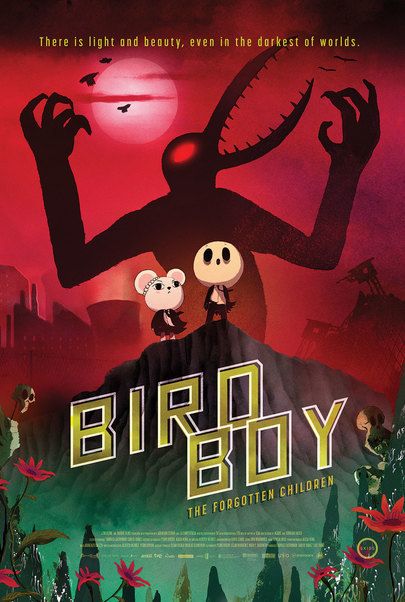

For the finale of our five-part tour of some of the more obscure films competing for the Best Animated Feature Oscar, we turn to a film that premiered over two years ago, but has only just opened in the U.S. this very weekend: the Spanish psychological horror cartoon Birdboy: The Forgotten Chidlren. The film is based on the comic Psiconautas by Alberto Vázquez, who co-writes and co-directs with Pedro Rivero; it's the duo's second film based on these characters, following the 2011 short Birdman, which serves as the new feature's backstory (the short is available online).

For the finale of our five-part tour of some of the more obscure films competing for the Best Animated Feature Oscar, we turn to a film that premiered over two years ago, but has only just opened in the U.S. this very weekend: the Spanish psychological horror cartoon Birdboy: The Forgotten Chidlren. The film is based on the comic Psiconautas by Alberto Vázquez, who co-writes and co-directs with Pedro Rivero; it's the duo's second film based on these characters, following the 2011 short Birdman, which serves as the new feature's backstory (the short is available online).

The basic hook here couldn't be any more direct or nasty-minded. This is a silly talking animal film warped into a portrait of the world as bleak, hopeless hell. "Psychological horror," I called it, because I'd be hard pressed to name any better category, but that's not really enough to communicate the sheer, visceral nastiness of this film. It's a mere 76 minutes long, and even that's almost too long to spend with the film's altogether putrescent depiction of a world that has died, with the survivors still tottering around in the corpse of that world, forced to confront some truly cruel moments. Also, they're fuzzy critters.

The jarring contrast, naturally enough, makes the depiction of cruelty and misery even sharper and more penetrating. You just haven't seen ironic counterpoint until you watch the silhouettes of cartoon animals stripped to the bone in a nuclear blast, something that has come and gone before the film's five-minute mark

There's little plot to speak of, but the primary one of the film's intersecting scenario follows a trio of adolescent animals, rendered in the pastel colors and round shapes of the most babyish cartoon. Dinki is a white mouse, chafing under the repressive religiosity of her stepfather and mother; Sanda is a blue rabbit experiencing violent auditory hallucinations, which manifest as little pitch black rabbits with piercing red eyes; Little Fox is a sensitive, fragile soul, who wanders through the movie with those two as his best friends, looking like everything he sees is going to make him burst into tears. They live on post-apocalyptic island that still appears to think that civilization is going on. Dinki was once in love with Birdboy, a hollow-eyed figure in a funereal suit, who nervously skitters around the woods, evading the cops, while he uses heroin to keep at bay his nightmare visions of crow-like demons ripping his organs out.

There's more to it than that, with several colorful grotesques populating a world that has apparently given itself over to suffering – even the talking alarm clocks in this universe have the capacity to feel terror and pain, as do other normally inanimate objects. But the bulk of it here: this is a film about the limitations of having a kind heart in a fundamentally rotten world, and the desperate need to maintain some vague semblance of hope at all costs in such a world. If that sounds just too damn dark for its own good, well, that's because it is. It is not, however, nihilism without any point: the filmmakers have a keen sense of sympathy for their unhappy heroes, and a firm grasp on the moral injustice of the world. There's more than a little allegory here, though it's not always entirely clear what that allegory is for. The basic human need for optimism in dark times, I suppose, and that's certainly not an unwelcome message here in 2017.

In what makes for a nearly faultless marriage of theme and style, Birdboy emerges as one of the year's more startling and striking pieces of animation (though maybe less so than the 2011 short; it's more polished, but less acutely stylized). A horror film it's to be, and the imagery is absolutely that: there are nightmare visions in this film that use the mutability of animated bodies and the inconsistency of animated space to depict some legitimately terrifying moments of unearthly violence. And yet, there are also those three kids, sketched in gently, welcoming shapes and colors, with big, iconic expressions on their simple line-drawing faces.

The tension the film drags out of this straightforward visual imbalance is hard to overstate. Birdboy is a deeply unsettling film, presenting a sick landscape in simple hues and sketchy lines, like a middle-school notebook filled with the ravings of a millenarian street preacher. It looks like a children's film, and it has the soul of a Scandinavian art film. There's real power here; I won't pretend that I always liked how the film made me feel, but the intensity of that feeling is remarkable, a firm rebuke to the idea that animated films should be comforting or domesticated in some way. Your mileage will undoubtedly vary as to whether this is to be sought out or not, but It hits hard and it doesn't let up, and its considerably empathetic depiction of pain makes for an unexpectedly humanist film, regardless if the humans are four-foot-tall talking mice.

Reviews of Eligible Animated Contenders:

In this Corner of the World (Japan) reviewed by Tim Brayton

The Big Bad Fox (France) reviewed by Tim Brayton

Coco (US) reviewed by Jorge Molina

The Girl Without Hands (France) reviewed by Tim Brayton

The Breadwinner (Ireland/Canada/Luxembourg) reviewed by Nathaniel

The Emoji Movie (US) reviewed by Sean Donovan

The Boss Baby (US) reviewed by Nathaniel R

Loving Vincent (UK/Poland) reviewed by Tim Brayton

Smurfs: The Lost Village (US) reviewed by Tim Brayton