"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. Here's Daniel Walber...

The United States may have entered World War II late, but American studios didn’t wait nearly as long to start making propaganda. Hollywood produced a number of pro-Allied films before the American entry into the war, from A Yankee in the RAF to the comparatively subtle Sergeant York. Though this ruffled some feathers in Washington, the debate became moot in December of 1941.

The United States may have entered World War II late, but American studios didn’t wait nearly as long to start making propaganda. Hollywood produced a number of pro-Allied films before the American entry into the war, from A Yankee in the RAF to the comparatively subtle Sergeant York. Though this ruffled some feathers in Washington, the debate became moot in December of 1941.

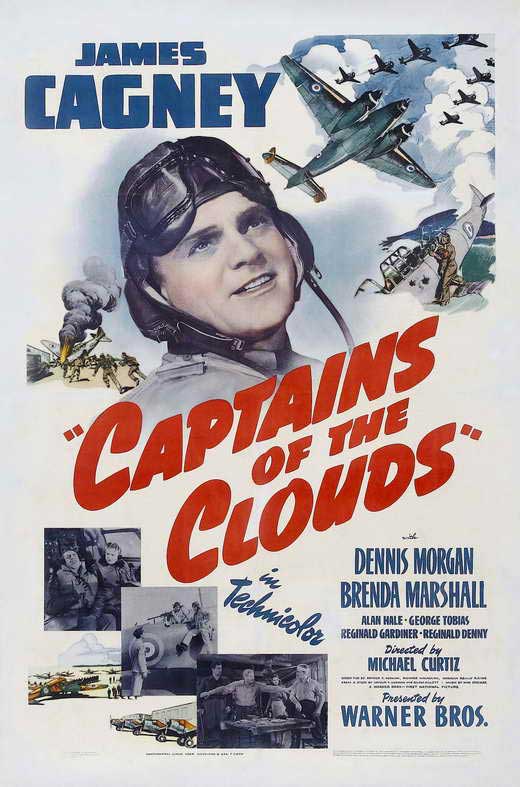

Captains of the Clouds falls right on the cusp, shot before Pearl Harbor but released in February of 1942. The film, directed by Michael Curtiz, was intended to drum up support for the Canadian war effort. The first major Hollywood production to be shot north of the border, it’s a technicolor extravaganza starring James Cagney and the Royal Canadian Air Force.

It also received two Oscar nominations. Sol Polito was recognized in the Best Cinematography category for the film’s breathtaking aerial sequences, a no-brainer.

The nominated work of art director Ted Smith and set decorator Casey Roberts, however, is less flashy...

The wilderness cabin interiors seem accurate, but not quite worthy of a full column. Instead, I’ll talk about the production’s much more obvious strength: the planes.

The film begins in rural Northern Ontario, where Brian MacLean (Cagney) and his friendly rivals transport people and cargo for cash. Their seaplanes are painted to stand out against the light blue sky and the forest green. MacLean flies a Noorduyn Norseman, the first ever made.

It crashed in 1952, but its remains are on view at the Canadian Bushplane Heritage Center in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. The rest of the bush planes used in the film are just as charismatically colored, including this Waco ZQC-6.

The plot turns when MacLean runs away with Emily (Brenda Marshall), the fiance of his friend Johnny (Dennis Morgan), to the apparently thrilling city of sin that was Ottawa in the early days of the Second World War. After a confrontation, Johnny is convinced to join the RCAF by a montage of enlistment posters.

MacLean and his buddies eventually enlist as well, moved by a weird version of Winston Churchill’s “We shall fight on the beaches” speech, re-recorded by an impersonator. Too old for combat, they are ordered to teach. MacLean, ever-insubordinate, is shuttled from base to base. Each successive location is introduced by a variation on the same sign.

From here on out the movie is all about the armada of colorful aircraft. There are countless yellow Harvard IIs, single-engine aircraft that were used by both the British and American air forces to train their pilots.

Bright and sleek, the little Harvard II is perfect. But this being a big Hollywood production, one model isn’t nearly enough. There are also Yales, Nomads, Finch IIs, Electra Juniors and more. That list may sound bewildering, but you don’t need to be a knowledgeable contributor to the IMPDB (Internet Movie Plane Database) to appreciate the design variety.

The thrill of the crash and the resulting angular horror are even more viscerally compelling.

The final stroke of genius comes when MacLean and his buddies are ordered to taxi some bombers over to England. In a sequence shot over the Atlantic Ocean near the RCAF base in Halifax, a lone Nazi fighter strikes the unarmed convoy. The role of the Luftwaffe Messerschmidt is played by a Hawker Hurricane, the plane responsible for 60% of the RAF’s air victories during the Battle of Britain. Painted a dark grey and anointed with German markings, it hovers above its prey.

The stunt pilot was Dal Russel, a veteran of the Battle of Britain. After filming, he took a short joy ride over the city of Halifax and scared the living daylights out of its citizens. Mercifully, local anti-aircraft gunners were warned about the shoot.

These days Captains of the Clouds is mostly remembered by aviation enthusiasts, which is understandable. The script has problems and some of the supporting performances collapse next to Cagney. But it has its virtues, enough to merit a 75th anniversary revisit. You don’t need to be able to tell the difference between a Northrup A-17A Nomad and a Lockheed L-12A Electra Junior to appreciate the spectacle. I certainly can’t.