It's a Pedro Party all week. Here's Lynn Lee on her introduction to Almodóvar...

To all actresses who have played actresses. To all women who act. To men who act and become women. To all the people who want to be mothers. To my mother.”

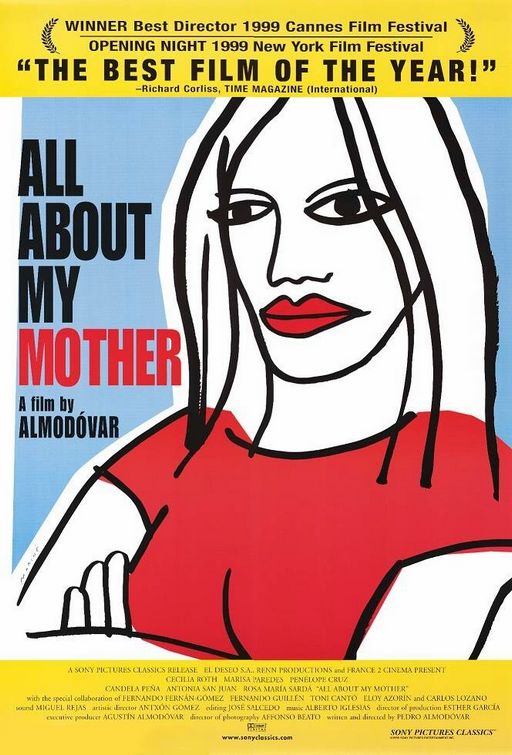

All About My Mother was the first Almodovar film I ever saw, and as it happens, I saw it with my own mother. I don’t remember why I picked it for us to see together. It certainly wasn’t because of the title or because I thought it would be something she’d particularly like. In fact, if I’d thought about it more, I might have been anxious that she would find it too outré. Or for that matter, that I would; as both a movie lover and a young adult, I was just beginning to learn what was out there and how far it stretched beyond my own personal experience.

To our credit, or rather to Almodovar’s, there was no reason for such trepidation...

My mother enjoyed the movie, and as for me, if not quite love at first sight, it was close. I’d never seen anything like it. Those vibrant colors – especially the reds! The unabashed theatricality! The hypercharged emotions! But at the same time, I was struck by the absolute realness underlying the soap-opera melodrama and the performative aspects of the characters – an authenticity all the more authentic for being constructed. Or, to quote that glorious scene-stealer, Agrado...

My mother enjoyed the movie, and as for me, if not quite love at first sight, it was close. I’d never seen anything like it. Those vibrant colors – especially the reds! The unabashed theatricality! The hypercharged emotions! But at the same time, I was struck by the absolute realness underlying the soap-opera melodrama and the performative aspects of the characters – an authenticity all the more authentic for being constructed. Or, to quote that glorious scene-stealer, Agrado...

You are more authentic the more you resemble what you’ve dreamed of being.”

It was also the first time I’d ever seen queer and transgender characters treated with such easy, matter-of-fact humanity on screen, and the first time I remember seeing a movie so completely dominated by women. Patriarchal society is defined primarily through its absence – Esteban’s long-lost father, Rosa’s stricken by Alzheimer’s – or through the filter of acting, most prominently in the form of A Streetcar Named Desire, a recurring reference point but one whose masculine tropes are constantly, slyly being undercut by the players. Meanwhile, the film’s three most important male figures, the three generations of Esteban – one of whom chooses femininity, one of whom dies near the beginning of the film, and one of whom is born near the end of it – hover at the margins of the narrative, influencing its direction but not its essential nature. Little wonder they barely register next to the far more memorable women: impish Agrado (Antonia San Juan), putting her own irreverent, transgendered spin on the hooker with a heart of gold; martyr-like Rosa (a startlingly young Penelope Cruz), imperious yet vulnerable Huma (Marisa Paredes), and, of course, the mother and nurturer to them all, Manuela (Cecilia Roth).

The latter, by the way, is particularly rewarding on rewatch. It’s not easy playing the straight (wo)man amid such a colorful cast of characters, and there’s a remarkable depth and poignancy to Manuela’s grief and the way she can’t help taking care of everyone even as she grieves. She’s the emotional linchpin of the film, the axis on which everything turns. If she’s perennially cast as a Stella surrounded by Blanches, she’s also the rare Stella who takes charge of the story; the Stella who seeks redemption and strives to be the sister and mother that Streetcar’s Stella ultimately fails to be. Manuela’s also something of an anti-Eve Harrington (All About Eve being the film’s other major touchstone/inspiration), the assistant who genuinely wants to support, not upstage or supersede, those she assists.

Nowhere are these qualities more apparent than in a quiet, lovely scene in which all four women meet for the first time at Manuela’s apartment. A bare, makeshift affair when she first returns to Barcelona, by this point the place is starting to come together and feel more like a home (tellingly, with more color, especially the signature Almodovarian red and reddish hues). Huma comes to smooth over a recent misunderstanding, while Manuela, who’s reluctantly taken in the ailing and pregnant Rosa, explains she can’t be Huma’s assistant anymore but suggests that Agrado take her place. This seems at first like a dubious proposition, even when Agrado herself sails in with her cava and ice cream and characteristic joie de vivre. Everything balances precariously on a dime as Agrado rattles on, until she cracks a joke about sucking cock and an amused Huma jokes back, and all of a sudden we know it’s going to work out. Awkwardness gives way to ease and that sense of female camaraderie that’s so quintessentially Almodovar yet never so warm and relaxed as it is here. The unifying presence of Manuela is felt without being forced, even if it lasts only a moment.

I have to think it was this organic propensity for drawing together disparate female personalities that my mom and I responded to so strongly all those years ago, and that still endures today. Almodovar would return to this theme even more powerfully in Volver, which is still my favorite of his films and which goes even farther in not just sidelining but (literally) slaying the straight-male patriarchy in favor of an all-embracing matriarchy. But he had its prototype in All About My Mother, a film that’s so gently subversive you almost don’t notice it’s subverting anything. If there were ever an Almodovar movie to introduce your mother to, this is the one. And not just because of the title.

Previously at our Pedro Party

- Dark Habits - Nathaniel R

- Alberto Iglesias's film scores - Chris Feil

- Women on the Verge... - Spencer Coile

- Male actors Pedro should work with - Nathaniel R

Pedro from the Archives

- Julieta - Manuel Betancourt

- Law of Desire's Shower Scene - Manuel Betancourt

- Chus Lampreave (RIP) - Nathaniel R

- The Skin I Live In - Michael Cusumano

- "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" Matador - Nathaniel R