by Sean Donovan

by Sean Donovan

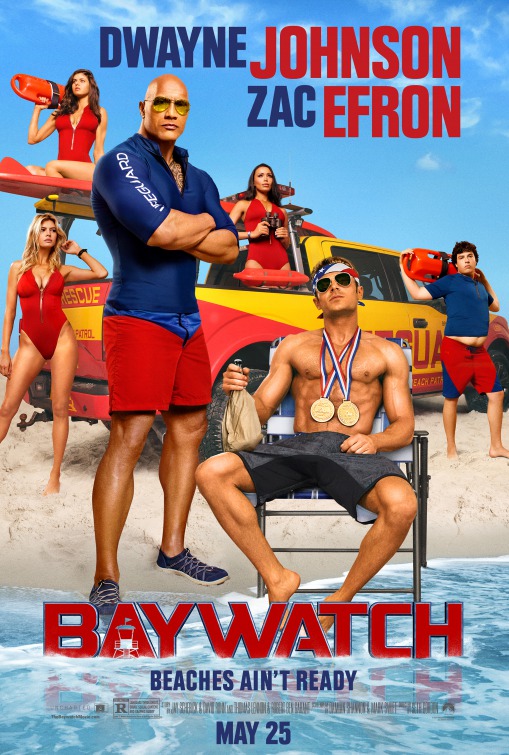

Of the men currently dominating American movie box offices, few are more men than Dwayne Johnson and Zac Efron. And by this I don’t mean to praise or value anything specific in their incarnations of masculinity, rather I mean that when one watches Dwayne Johnson or Zac Efron, it’s as if they are working at every fraction of a second to scream in reminder to you “I AM A MAN! I HAVE MUSCLES! I AM STRONG! I EAT MEAT! I PROVIDE FOR MY WIFE AND CHILDREN!” It’s a function of the danger men in real life often pose that masculinity isn’t something we can easily mock or laugh at.

Not so with Dwayne Johnson and Zac Efron (and to a lesser extent Chris Hemsworth). Masculinity is rarely sillier than in a Dwayne Johnson movie, the actor’s mind-boggling physique dominating every frame, each new performance somehow more muscled and over-the-top than before. Johnson’s instagram is a running tribute to the inflated absurdity of his sweat-drenched lifestyle. Efron, though not as fully the author of his own image as Dwayne Johnson, has found his greatest performances in Neighbors and its equally great sequel, where he plays up an arrogant frat-boy shtick, with peeks to the insecurities underneath, to absolute comic gold. Both allow us to look at hyper-masculinity as something laughable and campy, a cathartic moment we rarely get elsewhere.

For these reasons, putting these actors together looked to me like an automatic win. To sweeten the deal, it’s in a film based on Baywatch: if there’s anywhere Johnson and Efron would seem comfortable, it’s in a property entirely devoted to glistening beach bodies. How could Baywatch possibly lose?

I went to the theater confidently discarding the film’s low Rotten Tomatoes score- “it’s just that mainstream critics don’t understand camp,” I foolishly convinced myself. But within the first half hour it became abundantly clear this was not the Baywatch to which I felt entitled. The film’s title card is sublime, gargantuan letters emerging from the sea as Mitch Buchannon (Johnson) hulks towards the camera, dolphins leaping into the air. It is extreme and it is overflowing, exactly what the rest of the film should have been, had the filmmakers not made the surprising choice to scale down campy bombast wherever they could.

Baywatch is an action-comedy, and there is nothing inherently wrong with that. What is wrong is that it isn’t fun. There are many successful action-comedies, even some like 21 Jump Street that also root from cheesy nineties television, but that film’s police setting made action the obvious choice. Why did Baywatch have to be an action-comedy? Our co-lead, disgraced Olympian Matt Brody (Efron) several times begs the obvious question: why are lifeguards the proper line of defense against corrupt city officials and drug traffickers? His criticisms go unanswered, as our hero lifeguards rush off to the next major set piece. The writers slip these coy winks to the audience in through Efron’s character, as if to say “we know this is silly, but if we acknowledge it that means it’s funny, right?” Wrong.

Baywatch’s smug smirk of a reaction to its own sloppiness makes it even more infuriating. That’s all the comedy of Baywatch is: casual smirks clumsily taped on to an existing “stop the drug traffickers” plot. Priyanka Chopra, as the socialite by day, drug lord by night, escapes the wreckage mostly unscathed, due to her powerful diva attitude and an excellent wardrobe.

With the comedy nothing more than a gesture, Johnson and Efron are used here primarily as action movies leads. Their performances of ludicrous hyper-masculinity are not the comic focus of the film, but are rather supposed to be taken sincerely, as the men we would want protecting our beaches. This perfect opportunity to laugh with two of the best vessels for hyper-masculine camp is utterly deflated by the film staring at them uncritically, accepting their he-man grandeur as a simple fact of the universe. Dwayne Johnson, ever the professional and truly capable comic actor that he is, does his best to save what he can, but it’s a losing battle.

And Zac Efron, continuing the dispiriting trend set off by Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates, is called on to be the comedic foil to Johnson’s straight man, a task he is fundamentally incapable of doing. Watch in horror as Zac performs a bit about mimicking racial outrage as a white person (he reacts incredulously to a black police officer generalizing lifeguards by repeating his phrase accusingly “YOU PEOPLE???”), and then goes back to the same joke minutes later, because once was apparently not enough. This goes down while legitimately talented comedians like Hannibal Buress and Rob Huebel wander around the film in search of a joke. Mike and Dave… called on Zac Efron to do impressions, so it could be worse.

But despite the many ways Baywatch disappoints, no other element of the film further signified I was cheated of a fun time at the movies than the existence of a prominent supporting character, almost a third lead, the nerdy bumbling junior lifeguard Ronnie (Jon Bass). Ronnie permanently dashes any hope that this film was out to celebrate the absurdity of Johnson and Efron’s over-the-top personae, because he plays squarely to a prototypical white straight male viewer. Ronnie trips, Ronnie falls down, Ronnie falls behind the rest of the crew, Ronnie’s penis is discussed entirely too much. And Ronnie lusts after the girl, CJ, played by Kelly Rohrbach, the actress forced into one long teenage boy sex dream that is both obsessively leering and dully repetitive. One imagines a terrible room of Hollywood executives deciding that Baywatch needs an “everyman,” that Dwayne and Zac are too un-relatable to their base male consumer. And there comes Ronnie. The exact joy of Dwayne and Zac is in their non-everyman-ness, their excess of masculinity to its point of outright parody. Ronnie serves only to take us out of our camp fantasies, and remind us of the exact mediocre male consumer this film was made for.

Grade: D