"The Furniture" a weekly series on Production Design by Daniel Walber

The 1951 box office was topped by Quo Vadis, a sword-and-sandal epic with thumping Christian overtones that cost well over $7 million. Crowds flocked to see Peter Ustinov’s Nero fiddle over the burning wreckage of Rome. And when the Academy Awards came around, the film picked up eight nominations.

Nevertheless, this is not column about Quo Vadis. If you scan a bit lower on the list of 1951’s biggest moneymakers, you’ll find David and Bathsheba. Next to Nero’s gold, it seems minor. It grossed less and scored fewer Oscar nominations. But it makes up for this deficit in sparkle with its unique character, intimate drama in a biblical package. The Oscar nominated production design, sprung from a much lower budget, illustrates that as much as anything else...

It opens on King David (Gregory Peck) in his later years, bored ruler of a kingdom at war. One night he looks out from his balcony and sees the beautiful Bathsheba (Susan Hayward) bathing. Before you know it he’s brainstorming ways to get rid of her bland husband Uriah, a crime of passion that shakes the moral bedrock of an entire nation.

Another film might opt for a shrieking condemnation of infidelity with fire, brimstone and tacky costumes. Not here. The sets feel almost modest. The Jerusalem conceived by art directors George Davis and Lyle Wheeler in the Arizona desert is no vibrant metropolis. The sets, decorated by Paul Fox and Thomas Little, couldn’t be further from the orgiastic vomitoriums of the Caesars.

David, after all, began as a shepherd. Many scenes feature open fields, emphasizing pastoralist foundation of Judaean ethics. The Ark of the Covenant is met, not by a triumphal arch of marble and gold, but by a colonnade of palm fronds.

The palace itself is not opulent, in spite of its size. The throne room appears both grand and cramped, dominated by rows of plain stone columns.

David’s private quarters have a fair bit more decor, but none of it is particularly glitzy. His table is low to the floor, accompanied by a few animal skin cushions. The walls are accented by graphic tapestries and metal grilles, canvasses for dramatic shadow.

Opulence is reserved only for religion, in this case the Ark of the Covenant. Built from wood and plated in gold (paint), this version has an especially voluptuous pair of angels. It would eventually come into the possession of Debbie Reynolds, who sold it at auction in 2011.

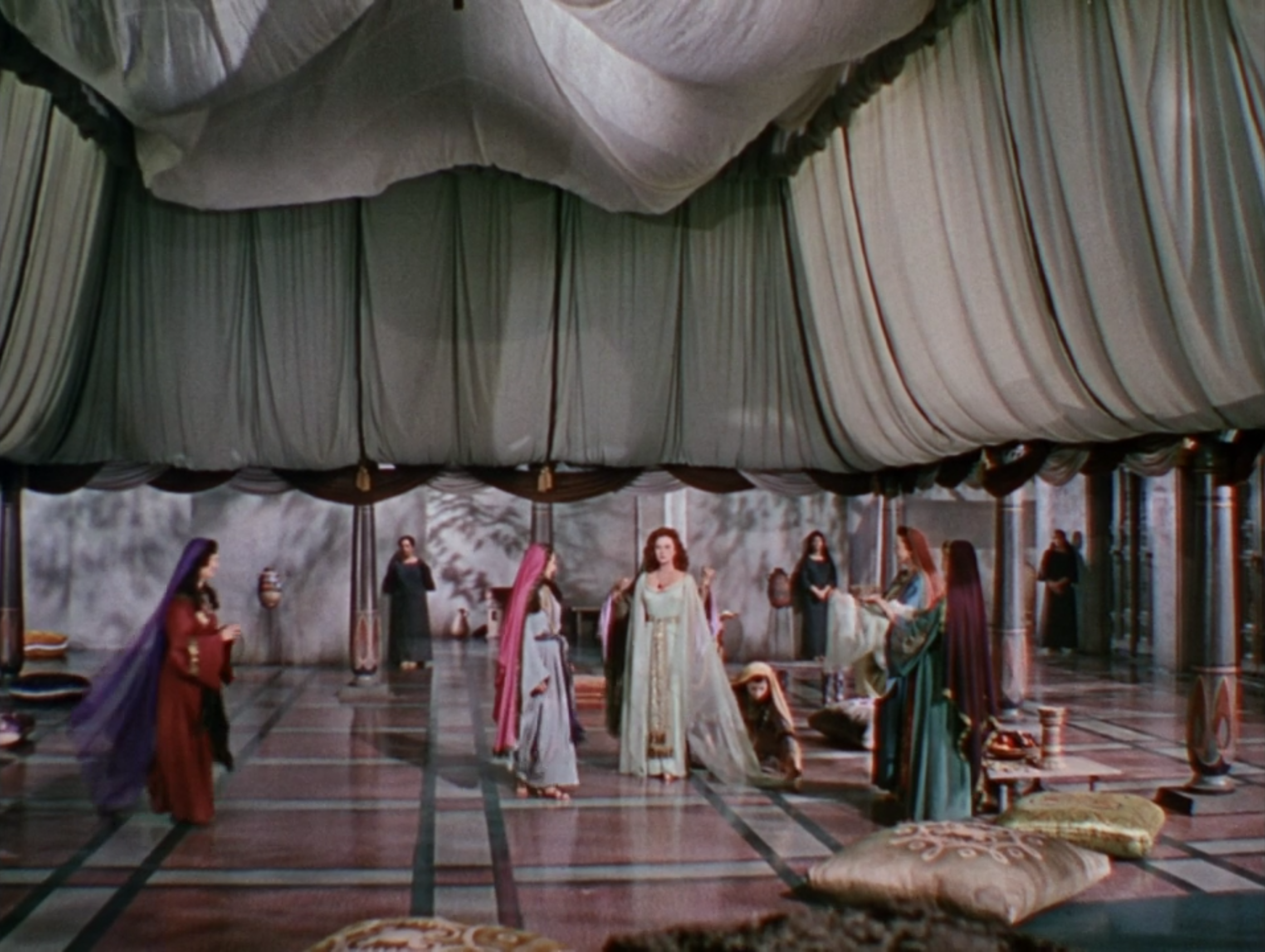

This is why a later scene of ceremony feels a bit sinful. After Uriah has been killed, the king marries Bathsheba. Her bridal chamber is crowned by a heavenly firmament of sheets, billowing above the mauve marble floor.

Accented by pillows and carved columns, this scene has a more varied color palette than any other in the film.

The marriage is condemned by God. The first child that Bathsheba conceived dies. And the countryside, the pastoral home of this newly-monarchical society, is ravaged by the winds.

But writer Philip Dunne and director Henry King resist the urge to rain down fire and brimstone. Bathsheba is presented more sympathetically than David’s first wife, Michal. Uriah, meanwhile, is portrayed as a neglectful husband whose true love is the battlefield. It is almost as if he wants to die.

The design supports this subtle moral landscape. The palace, rather than exaggerating the power and image of the king, dwarfs him. Cinematographer Leon Shamroy prefers to keep Peck in the lower third of the frame, underneath the powerful columns and high ceilings. Wherever he walks, his royal and personal burdens hover above.

In the end, his humility is what restores order to the palace and peace to the fields. Through the combined metaphorical power of the divine Ark and the modest shepherd’s lyre, he learns to repent.

Just glancing at the title and the budget, David and Bathsheba might be lumped in with other ‘50s religious epics. But it barely fits the mold. It’s a slow, contemplative drama of ethics and repentance, designed with an emphasis on psychology. It’s an unexpectedly sober work in a genre all its own.