by Nathaniel R

by Nathaniel R

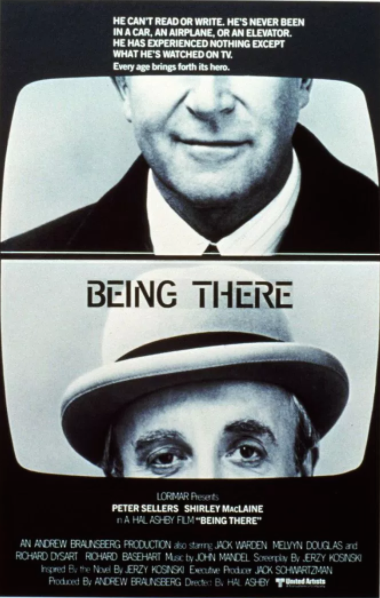

Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979) is a fortune teller. And the future it foretells isn’t rosy. The classic film about a TV-loving cypher who Forrest Gumps his way into history is approaching its 40th anniversary, but its essential viewing for the right now. Don't wait until 2019 to see it.

Among the film’s many queasy previews of life in the early 21st century is the proliferation of screens. Here that takes the shape of television, with Ashby frequent crosscutting to whatever is on the TV in a given scene. Though the content we see is recognizably dated, its intrusion is evergreen.

Hidden within the prophecy of multiple screens replacing actual experience, is an even sharper notion of the screen as a mirror...

For the first reel of Being There we mostly watch the protagonist Chance (Peter Sellers) watching television. He often mimics the body language he sees there. When he’s forced out of his longterm home, a home he appears never to have existed outside of suggesting that he’s an allegorical inkblot rather than a character, he wanders the city streets of Washington DC. The film’s first definitive image is a shot of Chance noticing himself on a TV screen in a window. He is puzzled by his reflection (which is, in actuality, a store camera recording him) as if he’s never encountered a mirror.

When he gets the chance to be on TV again, his stone face betrays an otherwise rarely seen excitement. It’s no surprise when we later see him watching himself on TV, his image doubled yet again.

But the movie’s true genius in this regard is not an easy potshot at the narcissism so familiar to us in the age of selfies and YouTube. Rather it’s in the way it relocates that tendency, dropping it into a sociopolitcal context. In the 21st century politics are more partisan than ever; we regularly hear that we’re all living within bubbles and echo chambers, perpetually wanting our own opinions reflected back at us through others.

Chance’s poker face and his tendency to answer questions by essentially repeating them, allows him to becomes a mirror himself. Whoever speaks to him is free to project their own fantasies on to him or hear what they want to hear when he speaks. He gladly accommodates the impulse, an ever amiable blank slate.

Nowhere is this more true than in the house of Eve and Benjamin Rand (Shirley Maclaine and Melvyn Douglas) a wealthy couple with an outsized influence on the ruling class. Benjamin immediately transfers his political capital and, essentially, his wife to Chance. Eve throws herself at an unresponsive Chance. In the absence of an exchange of bodily fluids, she sloppily projects all over him instead.

In one of the film’s most overtly comic scenes, Eve misinterprets Chance’s “I like to watch” mantra, and masturbates to orgasm. The next morning, still blissful, she doesn’t even know how well she’s summarizing this idea of projection and self-regard.

You uncoil my wants; desire

flows within me, and when you

watch me my passion dissolves

it. You set me free. I

reveal myself to myself and I

am drenched and purged.

Being There doesn’t just evoke the narcissism and feedback loops of our current culture. Other prophesies include but are not limited to the demise of newspapers, the media’s coddling of ignorance as a virtue, the rise of totally unprepared political figures with no understanding of politics, and even a hilariously sharp take down of “white privilege” which was a concept that had been introduced before Being There but has only recently embedded itself in the mainstream vernacular. Being There began life as a satire in 1979 — in 2017 it’s a tragicomedy and, frankly, something of a horror film.