"The Furniture" is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

The films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, though they are many and varied, almost always have striking production design. The obvious examples include the ‘70s scifi chic of World on a Wire and the opulent apartment of Petra von Kant, but it's true of his whole catalogue. The design of Querelle is as bold as it is aroused. And as of this week it’s new to FilmStruck, a place where you can find tons of design classics (like La Ronde and Great Expectations, two of my favorites).

The films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, though they are many and varied, almost always have striking production design. The obvious examples include the ‘70s scifi chic of World on a Wire and the opulent apartment of Petra von Kant, but it's true of his whole catalogue. The design of Querelle is as bold as it is aroused. And as of this week it’s new to FilmStruck, a place where you can find tons of design classics (like La Ronde and Great Expectations, two of my favorites).

Querelle got terrible reviews when it opened in 1982. It’s often considered an oddity of excess at the end of a career built on precision, an oversexed and underwritten mess with little to say and too much to show.

That’s nonsense. Sure, it's a lot, including the work of production designer Rolf Zehetbauer and art director Walter Richarz. But what most of the reviews seem to have missed is that Querelle isn’t just about sex. It’s about power, and the way that sex between men can be as much an exchange of control as it is an exchange of fluids.

The first shot of Le Vengeur, the ship on which Querelle (Brad Davis) serves, makes its own hierarchy very clear. The men, many of them shirtless, work through the heat. Lieutenant Sablon (Franco Nero), their captain, watches through an open door from the privacy of his office.

He leers at Querelle, utterly enrapt by his beauty. The power in their relationship is as yet unresolved, and will remain so for quite a while. But every other relationship is bluntly worked through, from the moment Querelle enters the Feria. It’s the most infamous (and apparently only) bar and brothel in this version of Brest. It’s a shriek of sexual energy and comically explicit architecture.

But no one laughs. They jockey for position, quite literally, with the utmost concern. Querelle’s initial submission to Nono (Günther Kaufmann) is as intense as it is transactional. The same goes for his encounter with Mario (Burckhard Driest), a cop. His most complicated relationship is with Gil (Hanno Pöschl), a construction worker driven to murder. Now hiding quite literally beneath the action, Gil is ripe for Querelle to save him and love him.

Pöschl also plays Robert, Querelle’s brother, the only man in the film interested in upholding the illusions of heterosexual machismo. Any contact between Querelle and Gil, therefore, has this added layer. But every sexual encounter in the film is layered, in which arousal is only the surface. When Querelle first goes off with Mario, a guillotine even lurks in the background.

Querelle is a natural at this game of sweaty social politics. So when Vic (Dieter Schidor) refuses to participate, he takes it as a personal affront and kills him. There are no witnesses, despite the very un-erotically cruel light of day.

The spot is also not really secluded. The entire port seems to occupy a tiny area. The view from the police station, for example, includes both the murder location on the left and the ship on the right.

Yet despite the total unity of location, the characters often move quite independently. Sablon is often able to maneuver the town without being noticed, even participating in an utterly unexplained religious procession.

It feels equally impossible that in such a small place, Gil and his young companion Roger (Laurent Matet) are able to hide out in complete privacy.

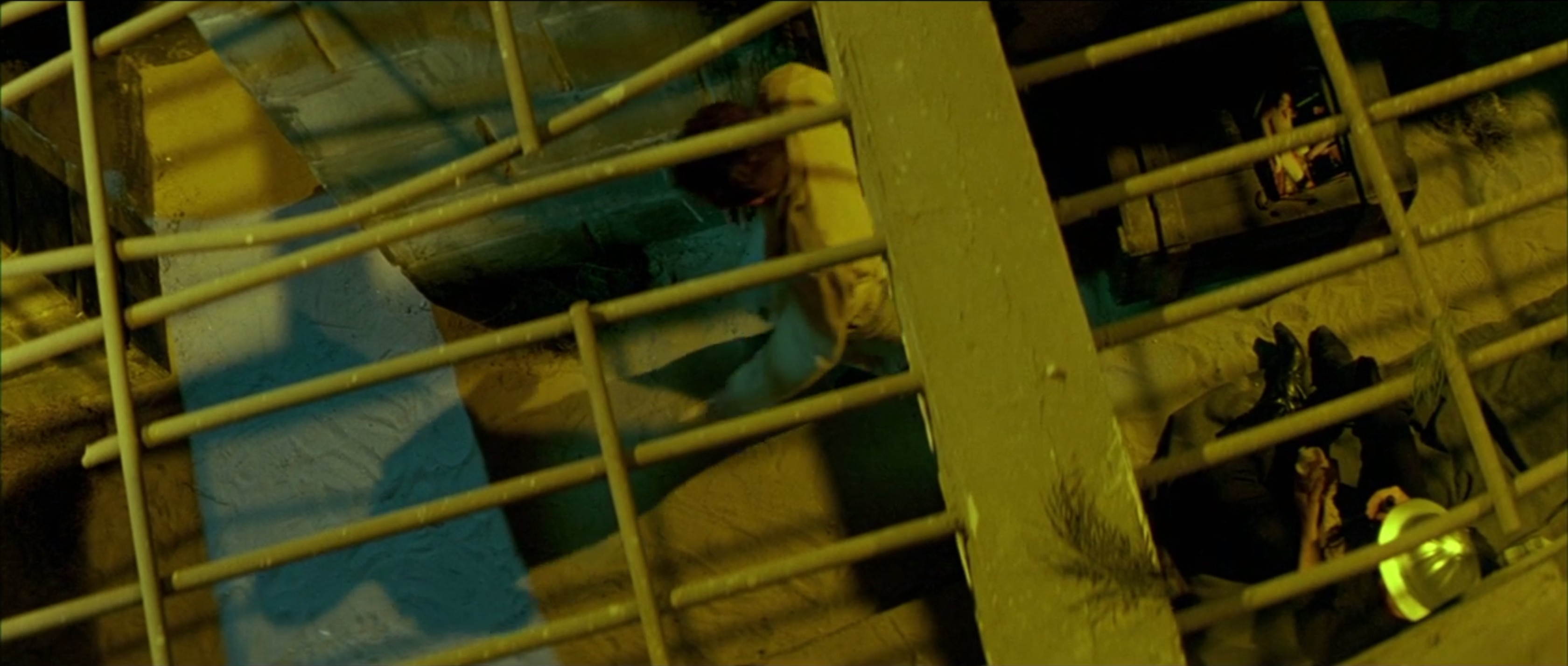

The scale and the complex narrative web combine to make every location seem like a cruising spot. Cinematographers Xaver Schwarzenberger and Josef Vavra participate as well, frequently relying on voyeuristic angles.

Sablon, the ultimate voyeur, is seen around corners and through cracks in the wall.

Yet in spite of this endless, community-wide sexual competition, harsh perspective lurks down by the sea wall. It’s warped, to be sure, framed by a burning sun of transparent artificiality. But it’s all the daylight that will ever be shined on these men, and its glare is inescapable.

This world exists in a perpetual twilight. There is neither the peace of night nor the clarity of day, fictional honesties that would serve no purpose in this world of frequent verbal mendacity and incessant erotic truth. And it is in this sweaty, briny atmosphere that Fassbinder gives the audience the strangest revolution. Even here, on the spiritually isolated island of Jean Genet, Billy Budd and the seafaring homosexual, a happy ending is possible.