"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Colossal is a movie built upon one very, very big metaphor. Gloria (Anne Hathaway) and Oscar (Jason Sudeikis) are highly destructive people, each at a different stage of addiction and personal crisis. They also have kaiju-sized avatars that tromp across Seoul every time they drunkenly stumble through a playground at 8:05am, the result of a bizarre electro-magical accident. It’s quite the premise.

Colossal is a movie built upon one very, very big metaphor. Gloria (Anne Hathaway) and Oscar (Jason Sudeikis) are highly destructive people, each at a different stage of addiction and personal crisis. They also have kaiju-sized avatars that tromp across Seoul every time they drunkenly stumble through a playground at 8:05am, the result of a bizarre electro-magical accident. It’s quite the premise.

But it works because director Nacho Vigalondo doesn’t rely exclusively on CGI monsters to get his point across. After all, they are only exaggerated versions of Gloria and Oscar, stomping through their lives. It matters not whether their feet land on a playground or through the first floor of an office building.

Or, as the case may be, their homes...

The most effective illustration of Gloria’s situation is the work of production designer Sue Chan, art director Roger Fires and set decorator Josh Plaw. Though this phase of her life is never quite aligned with a single location, each set is a new reflection of the emptiness beneath the mess.

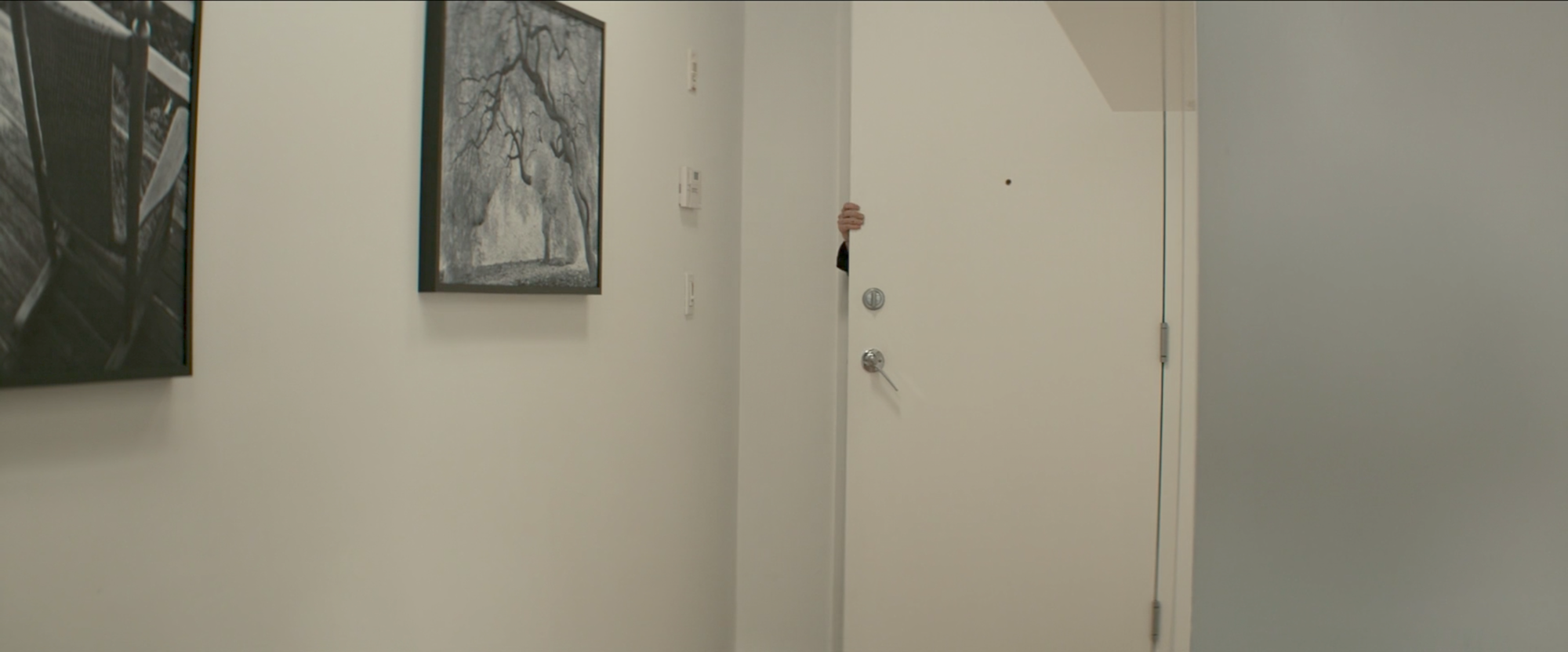

The film begins in New York City, where Gloria lives with Tim (Dan Stevens), her irritable and pompous boyfriend. Their apartment isn’t much of a home. The art on the walls has the generic, unobtrusive quality of a self-consciously hip hotel.

Their bed, meanwhile, is flanked by the blandly modern nighttables and lamps of an overpriced Hilton. Being kicked out of her apartment is obviously a blow, but one hardly gets the sense that Gloria was ever really settled in with Tim.

This characterization of Tim’s taste comes back to haunt Gloria later on, upon his misguided attempt to bully her into coming back. Sure enough, his room at the Holiday Inn Express is like a slightly cheaper version of his apartment.

After leaving Tim, Gloria moves into an old house, owned by her family but empty for some time. The only signs of human occupation are the occasional discrepancies in the wallpaper, shadows of forgotten furniture and artwork.

She doesn’t rush to furnish it either, content to crash on an air mattress. Gloria’s life is as washed out and empty as the building around her. It sleeps as she sleeps, affectless and with no compelling reason to wake up.

Her reconnection with Oscar is, therefore, a welcome sign of life. He offers her a job at his bar, and with it a small community of local drinkers. She’s especially energized by the discovery of some Old West decor, hidden away by Oscar. He thinks it’s embarrassing, but she loves it.

But Oscar quickly turns out to be much, much more destructive than Gloria. This eventually manifests in his choice to light a giant firework in the middle of the bar, a gesture of insane posturing intended to intimidate Tim and keep Gloria from leaving his spiral of misery.

It works, sort of. Most of his gestures have the same tenuous success, a temporary victory gained through shock. In a moment of vindictive charity, he decides to furnish Gloria’s house, unannounced. The van that shows up at her porch is overstuffed with a bizarre array of objects, from rugs to a globe.

Once it’s been unpacked, it becomes clear that Oscar’s sense of furniture is just as confused as his sense of self. There are plush red chairs and baskets of flowers, a tea set and ornate lamps. It looks like a misplaced period sitting room, utterly divorced from Gloria’s reality.

The explanation for this strange furniture becomes apparent when Gloria finally visits Oscar at home. Years since the death of his parents, he now lives alone in a nightmarish landscape of boxes and beer. His hoarding includes decades of stickers and tupperware, and far too many plants (though they all seem to be alive, an odd choice).

In the end, Gloria finally removes herself from Oscar, Tim and the kaiju. Every space in the film is an unhealthy one, and so she must leave them all. The ambiguous final shot offers no new direction. We are left with a ruined playground, a landscape purged of its decorated disease but without a catalog from which to build something better.