by Eric Blume

It’s difficult to believe that it’s fifty years this month that Arthur Penn’s 1967 classic Bonnie & Clyde debuted in theaters. On one hand, it’s been part of the American film imagination for so long, that it’s been colossally influential on many other movies. Yet every time you watch it, it feels as fresh, vital, and new as if it were just shot.

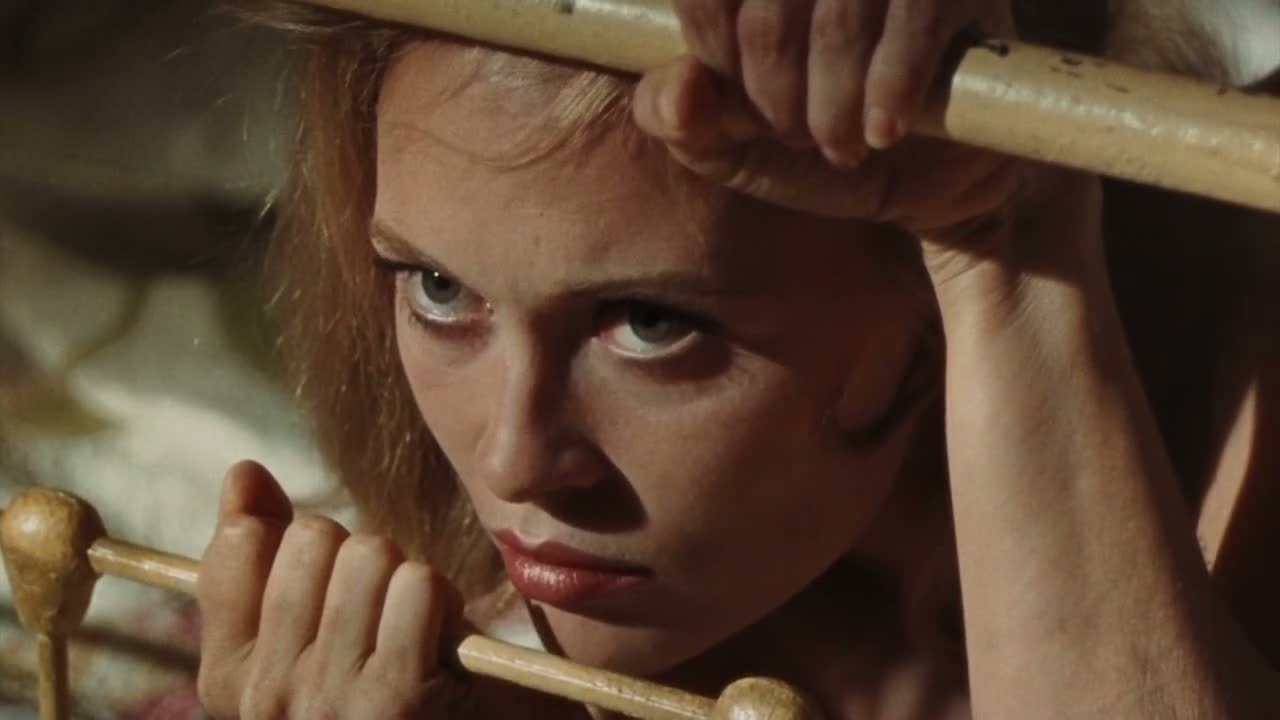

Surprisingly, the movie starts with Faye Dunaway’s Bonnie behind bars… holding onto the bars of the headboard of her bed...

She peers through them longingly: she starts the film as a prisoner, so her meeting with Warren Beatty’s Clyde, though it leads to her grisly end, sets her free.

Her furtive call out to him: “Boy! Boy!” and the scene that entails sets the tone for this blissful classic: it exists on both a practical and mythical level.

While Bonnie & Clyde is ostensibly about the story of two famous bank robbers in the 1930s, what Bonnie & Clyde really is about is the mythology of movies. Much has been written about how the film tapped into the 1960s counterculture, and how it had the audacity to turn its titular couple into rebels and heroes. This approach is indeed one of the most powerful and interesting elements of the film, especially since the filmmakers had the intelligence (and morality) to own the loss of life at each turn; the characters of Bonnie and Clyde may be glamorized, but their violence isn’t. The film borrows not only from Hollywood gangster movies, but also in tone from French New Wave, particularly Godard’s jump-cut impulses. Editor Dede Allen doesn’t execute jump cuts in the traditional sense (they don’t compress time, necessarily), but they have a hot-wire disconnect that isn’t traditional Hollywood editing. The film floats midway between something American and something European, while telling a purely American tale.

There’s a scene when the “Barrow Gang” first comes fully together, and you can barely wrap your mind around the five actors in the same frame. In addition to Beatty and Dunaway, who are doing movie-star acting of the highest caliber, you’ve got early Gene Hackman, providing the film’s most naturalistic performance; Michael J. Pollard, whose feral creepiness lends the movie a true sense of disquiet; and Oscar winner Estelle Parsons, whose acting is just so far out there. Director Arthur Penn somehow not only melds their varying styles into one coherent whole, he uses those styles to keep the movie on edge, and unpredictable.

Faye and Warren at the premiere in Paris

Faye and Warren at the premiere in Paris

And Penn fully knows what he had with Beatty and Dunaway. In a movie that’s largely about celebrity, these are two monumental movie star faces, at the height of their beauty. Penn composes them tightly, knowing they can hold the frame with power and authority. Beatty’s boyish charm and steely intelligence give the film its center. And while Dunaway lacks the technique of a great actress, she has moments of astonishing power. In the incredible, dreamlike scene where she sees her mother, Dunaway harnesses the pain and impact of the loss of any normal life for Bonnie. And of course the chemistry between these two stars is the stuff of movie heaven.

As the law slowly closes in on the Barrow gang, the film takes on a cumulative power that borders on overwhelming. The gruesome chain of violence rears back at the gang, and their respective ends come swiftly and forcefully. The film’s justifiably famous final sequence, as the birds fly away moments before the ballet of bullets riddle our “heroes”, remains one of the cinema’s great endings. These characters, who spend the film simultaneously fleeing from and clinging to normalcy, share one final look at each other where they unite in the fulfillment of their own inevitability.