"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Only 8 days until Oscar nominations! To mark the occasion, or perhaps to fill the time with something other than anticipation, let’s look back at the 8th Academy Awards. The year was 1935. Bette Davis won a consolation prize, Best Actress for Dangerous after the failure of a write-in campaign for 1934’s Of Human Bondage. John Ford won his first Oscar for The Informer, which beat Mutiny on the Bounty in nearly every category except Best Picture. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the film debut of Olivia de Havilland, won a write-in victory in Best Cinematography.

Only 8 days until Oscar nominations! To mark the occasion, or perhaps to fill the time with something other than anticipation, let’s look back at the 8th Academy Awards. The year was 1935. Bette Davis won a consolation prize, Best Actress for Dangerous after the failure of a write-in campaign for 1934’s Of Human Bondage. John Ford won his first Oscar for The Informer, which beat Mutiny on the Bounty in nearly every category except Best Picture. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the film debut of Olivia de Havilland, won a write-in victory in Best Cinematography.

This was the last year with only three nominees for Best Art Direction. The victory went to The Dark Angel, a drama of romance and World War One. Its biggest competition may have been The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, an imperial adventure set in the British Raj. It apparently promoted European superiority so effectively that Adolf Hitler saw it three times. It received seven nominations, winning for Best Assistant Director.

If this all seems dour, don’t worry...

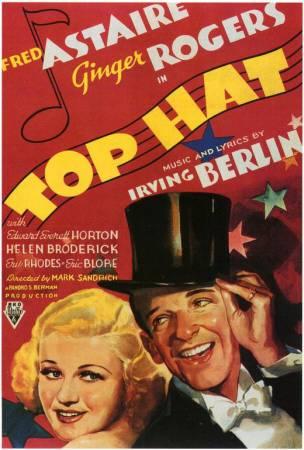

We’re going to look at the third nominee instead, one of the handful of 1935’s Oscar nominees to stand the test of time. Top Hat holds the distinction of being Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’s biggest box office hit. “Cheek to Cheek,” though it lost the Oscar to “Lullaby of Broadway,” might remain the pair’s most famous number. And the sets, portraying the interiors of two fancy hotels and a bewildering distillation of the Venetian Lido, are sleek and breathtaking.

This is the essential combination, of course, impressive sets that are neither so detailed nor so imposing that they distract from the dancing. Fred and Ginger glide across a little bridge to get from the main dance floor to their own private stage during “Cheek to Cheek,” passing a number of tastefully imagined architectural features.

The final ensemble number exhibits the same balance, though on a larger scale. As the chorus begins to pair off, the scope of the set is finally revealed. There’s a giant performance space amidst the opulence of the hotel and canal. One can glimpse a facsimile of the Basilica of San Marco in the background, the entire city reduced to a sort of dreamed nightclub.

All of that said, what makes Top Hat special are the sets that fill the time between these big musical numbers. The plot of the movie isn’t especially complicated. It’s a single case of mistaken identity that lasts nearly the whole film. What keeps it buoyant is the marvelous interior design, two fancy hotels that could very easily be a single building (or at least owned by the same chain).

There are graceful inflections everywhere, curved lines that suggest movement and charming illustrations on walls and doors. This Venetian bathroom, for example, sports an elegant crane. It has one leg raised, following a line from the neck to the shading of the wall.

The bedroom features depictions of musical instruments, adorned with white ribbons that complement the pillows, the sheets and the soft rugs on the floor.

They also suggest classical allusion, another visual theme that carries through the film. There’s an emphasis on simple beauty in form and design, every fixture a prelude to the dance.

My favorite detail is an actual dancer, a joyful Venetian in Carnival dress. Painted on the back of the door of the bridal suite, the body of his guitar echoes the curves of the decor. He, like everything else in the film, is a constant suggestion of movement, a reminder that in a Fred and Ginger picture the dancing never really stops.