John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

#43 —Margaret Thatcher, the polarizing British prime minister.

MATTHEW: After decades of heavy speculation about when, not if, Meryl Streep would finally win her third Academy Award, the most widely admired actress of all time picked up another trophy for a performance that may best be remembered as a textbook study in How to Win an Oscar. Despite stiff, down-to-the-wire competition from The Help’s eminently deserving Viola Davis, who transcended lackluster material in much the same way that Streep herself did in her most acclaimed tour de force, the actress sailed to victory after a season’s worth of ovations and exposure. The months preceding Streep’s first Oscar win in nearly 30 years found the acting legend accepting her eighth Golden Globe, her fourth New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress, her second BAFTA Film Award, her very first Vogue cover story, a Kennedy Center Honors lifetime achievement tribute, and endless publicity concerning one of the most challenging roles of her late career, that of Margaret Thatcher in what should rightfully be called Phyllida Lloyd’s The Iron Lady, but might just as suitably be described as Meryl Streep’s The Iron Lady. And when one truly considers the sheer size and notoriety of the role, who could have possibly topped Streep that year? Conversely, when truly considering the actual performance that returned Streep to Oscar glory, away from all the myth/history-making hubbub that surrounded it, one could be forgiven for wondering, Is that all there is?

The only thing more frustrating than this sympathetically humanizing portrait of a hateful conservative harridan is the participation of an extraordinary, broad-minded screen star like Streep in a project so ethically evasive and cinematically muddled. The Iron Lady is a sprawling and swollen piece of historical pageantry that neither outright heroizes nor criticizes its controversial subject, despite its painfully inept efforts at getting inside the mind of a late-in-life Thatcher as she struggles to remember her shameful political past through the fog of mental illness. (Such dubious political equivocacy reaches its absolute nadir in the film’s final moments, when screenwriter Abi Morgan summons up the empathy to applaud the forward-moving resilience of a repressive bigot.) Tasked with visualizing more staid material than Mamma Mia!, Lloyd’s filmmaking has been tamped down significantly from her incompetent musical travesty, retaining that movie’s crazed, rapid-fire editing while still failing to give us any reason why this director should have ever picked up a camera in the first place. Lloyd does Streep no favors nor challenges her beyond the superficial assignment of the role, which is to make us see the actress anew as she buries her own recognizable star persona beneath the even better-known facade of another star, albeit one of contemptible stature.

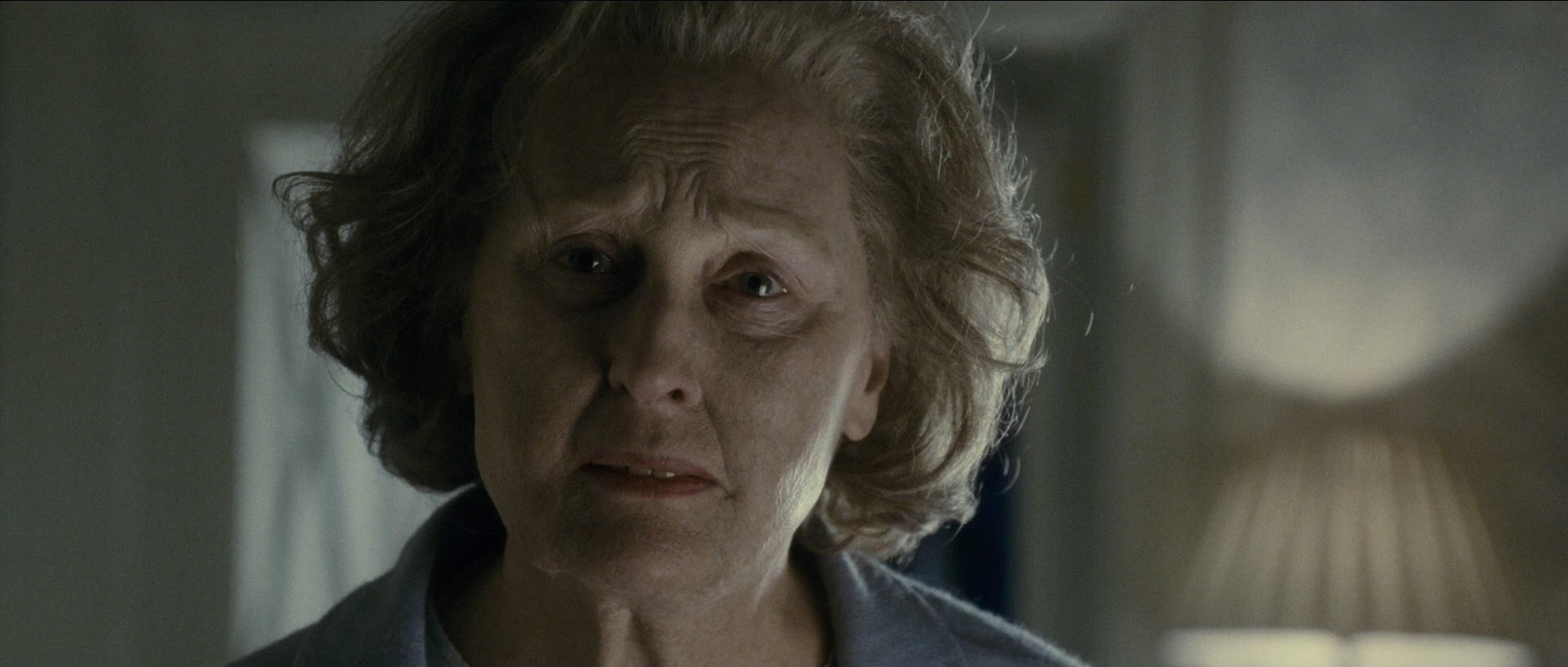

Lloyd and her cohorts betray an unseemly assumption that we can only be floored by the flashy flexing of Streep’s prized virtuosity, which is the film’s one and only raison d’être. This virtuosity is best showcased in the early, introductory old-age sequences, in which Streep, with the aid of the invaluable J. Roy Helland (rewarded by the Academy for his persuasive work here), mutes herself to the point of rendering her own identity as invisible as it possibly can be, leaving us with an elderly woman who is appropriately fuzzy and even startlingly characterless. In certain shots, Streep’s inscrutable, uncomprehending gaze expertly communicates the disappearance of a once-energetic mind that has left only a vast void in its place. For me, these are the lone peaks of a performance easier to praise for the fact of its existence than for any significant artistic merits.

Are you in agreement that The Iron Lady is nowhere near the most moving and multi-layered of Streep’s canonical turns, despite the Academy enshrining it among them?

JOHN: It was never about the performance. After years of Streep being the bridesmaid, it became impossible for voters to overlook this opportunity to give her an overdue third statue. Her Margaret Thatcher is exactly the type of strenuous, showy, and “important” role that garners an Oscar, even if the performance itself cannot hold a candle to Streep’s best work. Although Streep manages a precise feat of mimicry, her Thatcher is all surface technique and no soul beneath, a criticism that has trailed her throughout her career but has seldom been more earned. However, Streep is actually giving two performances in The Iron Lady: one charts the political rise and fall of Margaret Thatcher, and the other concerns an almost anonymous old woman suffering from dementia and reflecting upon her life; the nuance of the latter slightly redeems the bombast of the former. Hallucinating that her dead husband is still alive, fitfully recalling the specifics of her past, and prone to making unsupervised escapes to buy milk, the components of Streep’s old-age performance zero in on the sadness and vulnerability of this woman in her decaying mental state. In effect, this older incarnation is less overwrought and perhaps more sympathetic than Streep’s affected, younger Thatcher.

Sympathy for Margaret “I owe nothing to feminism” Thatcher? Let’s pause. What rankles me more than Streep’s lackluster performance and the inept filmmaking on display in The Iron Lady is the apolitical and feminist treatment lavished on an undeniably significant political career that was otherwise marked by failure and cruelty. It’s easy to sympathize with a historical figure if the specifics of said history are dulled beyond scrutiny; we learn little to nothing about Thatcher’s actual politics as Lloyd and Morgan peddle a feminist reading of her challenging rise to Prime Minister, highlighting the difficulties of being a woman in a field dominated exclusively by men.

Margaret Thatcher, the film claims, was an ambitious woman who struggled to be taken seriously, who, like many women, wanted a happy home and fulfilling career, even as her intelligence and appearance were undermined by scores of conventionally-minded men. It’s a fragmented Working Girl, but about the first female leader of the free world, whose political record of rampant unemployment, disastrous social policies, and taking milk away from school children, goes completely unexplored. We instead learn the bare fact that Margaret Thatcher was a woman, and whether we like her policies or not, she deserves some kind of awe-inspired respect for being the first woman Prime Minister.

In many ways, Thatcher remains the most challenging role of Streep’s career, not because of the heavy prosthetics or the difficult vocal patterns, but because she has rarely played a real-life character this monstrous. Streep remarked in her 2012 Vogue cover story:

With any character I play, where she is me is where I meet her. It’s very easy to set people at arm’s length and judge them. Yes, you can judge the policies and the actions and the shortcomings — but to live inside that body is another thing entirely. And it’s humbling on a certain level and infuriating, just like it is to live in your own body. Because you recognize your own failings, and I have no doubt that she recognized hers.”

Streep’s career has seen her humanize difficult women dissimilar from herself, but in films like A Cry in the Dark, The Manchurian Candidate, and The Devil Wears Prada, there is at least some exploration of her character’s mindset. Nothing about The Iron Lady suggests that Thatcher recognized her own failings, and little in Streep’s performance helped me to understand the interior life of this woman. Maybe this is a tall order to expect from the director of Mamma Mia!, but the more I think about The Iron Lady, the less there is to actually contemplate. Both empty and embarrassing, it’s a film I’m eager to forget, and a performance whose own legacy is best remembered as an Academy Award milestone.

Do you also think that Thatcher is an impossible character to portray either accurately or critically? Could you imagine this performance improved with a different director and writer?

MATTHEW: I agree that there are definitely few acting challenges with a greater degree of difficulty than inhabiting a not-so-distant historical figure of immediate physical and vocal recognizability, not to mention general ill-repute. The chances of disappointing an audience — or, more specifically, failing to convince them — remain imposingly high. But it’s not an altogether impossible task, and Streep at least proves up to the task and might have potentially excelled as Thatcher with smarter, tougher-minded collaborators than the hopeless Lloyd and Morgan. It’s not as if others haven’t dazzled with such a challenge.

In 2014, I saw the West End production of Moira Buffini’s Handbagged, a sharp and speculative political parody about “Mags” Thatcher’s meetings with Elizabeth II, in which the British actress Fenella Woolgar played the politician so skillfully and hilariously that she made one forget that there ever was a challenge to begin with. Woolgar, working with material both harder-hitting and tonally dissimilar than The Iron Lady, not only had a downright eerie knack for the physically uncanny — aided, like Streep, by hair and makeup wizards — but also managed, like Streep, to copy Thatcher’s voice to a T, nailing each and every word with the same fruity tone and feathery inflections for which Thatcher became known and ridiculed. Woolgar walked and held herself with the straight-backed and self-serious air of the actual Thatcher while tapping into a full-bodied form of satirization that didn’t rely upon any of the garish affectation of Streep’s much “straighter” take on the same woman. And although her hysterical performance was an unmistakable impersonation of the real figure, Woolgar was still able to reveal troublingly poignant facets of Thatcher through the humor of the piece. She brought the Iron Lady back down to human size in a way that Streep only manages to do when trapped beneath layers of octogenarian-aping prosthetics.

Elsewhere in the movie, Streep never suggests a warm-blooded human being beneath the false teeth, coats of foundation, and crinoline-stiff helmet of hair. When the actress strides through rooms with steely, probing shark eyes and raised chin, she cuts an indomitable figure, no question, but to what end? Instead of fleshing out a person with a pulse, Streep is just striking power poses, used as obvious counterpoints to all the tottering she will later do during the character’s dementia-stricken delusions. Even worse, Streep seems particularly unmindful of her co-stars, including a never more aggravating Jim Broadbent as husband Dennis, manifesting as something like a wrinkled, bothersome Jiminy Cricket, and Olivia Colman as perpetually disappointed daughter Carol. Such inattentiveness is perhaps fitting for a character made all the more unapproachable by her authority, but it’s nonetheless a rare and disappointing choice for an actress who frequently thrives off the energies and camaraderie of her fellow performers. Streep produces a formidable intensity in all of the expected scenes — an Oscar clip-ready tête-à-tête with the U.S. Secretary of State, a cabinet meeting in which an especially truculent Margaret belittles right-hand man Geoffrey Howe — and also in some of the everyday, at-home moments where Morgan’s rote words least deserve her exertion.

But this intensity never derives from within; like so much else in the performance, it’s a fitfully absorbing surface effect, nothing more. That Streep was rewarded for this emotionally obscure and unduly ostentatious characterization, linking her to Margaret Thatcher forevermore within the annals of Oscar history, can only be the result of a voting body that has placed an usual amount of distinction in the dubious act of imitation. By giving Streep her third Oscar for The Iron Lady, rather than, say, Silkwood or Ironweed or Postcards from the Edge or The Bridges of Madison County or Adaptation., the Academy again placed more value in conspicuous technical effort than the alchemical forces of an actor’s soul and imagination. These traits have defined the very best of Streep’s matchless achievements but are entirely undetectable beneath the unyielding armor of Margaret Thatcher.

Next Week: Hope Springs