Chris Feil is looking back at the films of Tamara Jenkins...

Tamara Jenkins doesn’t get nearly the love she deserves as one of the most rich voices in contemporary American comedy. Though maybe we could blame that on her short filmography that nevertheless remains pristinely unimpeachable. Or maybe it’s because she leaves us wanting for painful lengths of time between films, and makes it worth the wait. Her newest, Private Life, arrives Friday on Netflix after more than a decade since she gave us The Savages. And before that there was another decade gap following her 1998 debut Slums of Beverly Hills.

Tamara Jenkins doesn’t get nearly the love she deserves as one of the most rich voices in contemporary American comedy. Though maybe we could blame that on her short filmography that nevertheless remains pristinely unimpeachable. Or maybe it’s because she leaves us wanting for painful lengths of time between films, and makes it worth the wait. Her newest, Private Life, arrives Friday on Netflix after more than a decade since she gave us The Savages. And before that there was another decade gap following her 1998 debut Slums of Beverly Hills.

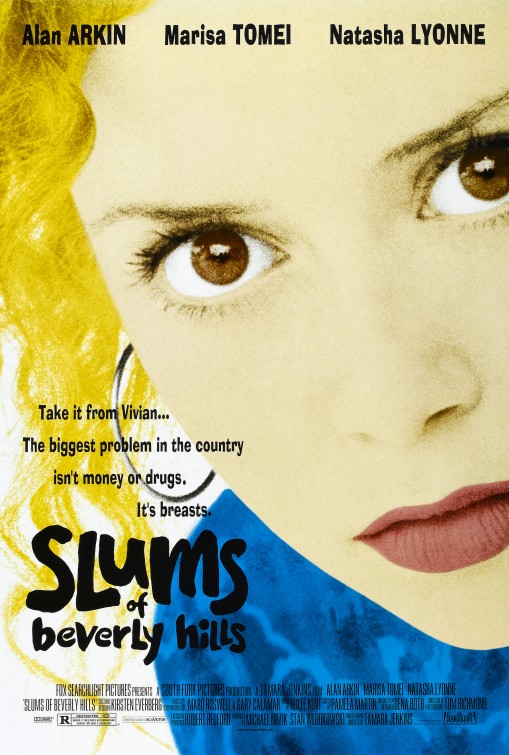

The film is most notorious for being the breakthrough role for Natasha Lyonne as the film’s hilarious teenage heroine Vivian. She belongs to another of Jenkins’ dysfunctional but affectionate family units, carted around 1970s California with her shifty father Murray and two dumbass brothers. Hers is a summer of firsts - her first bra, her first period, her first lay and first orgasm (separate, of course) - but Jenkins and Lyonne make it not-so-typical compared to less sharp coming-of-age tales. Opposite Alan Arkin as the father and Marisa Tomei as her fuckup aunt, Lyonne is a natural, exhaling comic brilliance by simply existing in Vivian’s restless malaise.

This first film is one entirely ripe for reassessment, sadly somewhat lost to time in the wake of lesser “quirky” comedies that have overshadowed it on the American independent landscape. Maybe it got lumped into the late-90s return of raunchy comedies, a subcategorization it both satisfies and subverts. There’s a delicacy to the sexual humor while it still remains a film that thinks bodies are hilarious and allows Lyonne and Tomei to dance goofily with a vibrator. Part of what allows it to cut through the bullshit of teen sex comedies is that it knows when and when not to be self-aware.

Twenty years on and the film feels more special than ever. Today we bemoan the lack of female expression or authorial voices in comedy, and the rarity of female sexual awakening to be seen outside of a male gaze onscreen. And then there is Slums, handling all of these points with casual ease and humanist warmth. Vivian deals with pressures both spoken and inferred, feels shame over her body while her brothers loaf around in their underwear. Part of Vivian’s coming of age is to discover her dad isn’t just a lovable louse, but also reconciling that he may be an unforgivable one as well. As tender as it is uproariously unflinching, Slums of Beverly Hills is just quietly waiting for us to notice that it’s something of a classic.

Slums is also packed with loads of underappreciated flashpoints in peak form: Tomei’s comedic chops, David Krumholtz’s putz-everyman charm, and the plushness of shag carpet (seriously, the film even has convincing love for 70s tackiness).

But Jenkins in particular is the voice that shines through brightest, an emergence that maybe we would be able to better appreciate now for the rarity of its feminine approach to youthful self-discovery. Also distinct is the writer/director’s ability to chart a character’s growth as their understanding of their particular family dynamic evolves amid slow-arriving crisis. Jenkins’ films have an uncommon balance of unassuming toughness and graciousness for her characters, and Slums is the one that pitches it more towards the outright laughs than the melancholy. But mostly, it’s one that deserves its due among the best of an era.