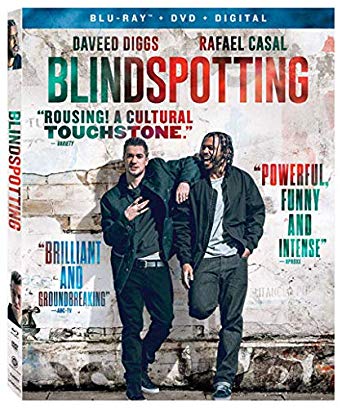

Lynn Lee on Blindspotting, new on Blu-Ray and DVD today

It must be something in the air. Or water. Or just our general 21st century American zeitgeist as we come to grips with how far we are from anything close to a “post-racial” dialogue. Whatever it is, 2018 is turning out to be the year for movies about racial code switching. It’s the common thread that links projects as disparate as the gonzo anti-capitalist satire of Sorry to Bother You, the stranger-than-fiction part-comedy, part-true crime thriller BlacKkKlansman, and the Black Lives Matter-inflected YA drama The Hate U Give. At the heart of each film is a black protagonist who, having mastered the art of speaking “white,” ultimately discovers its limits as a means of challenging society’s white-dominated power structure.

It must be something in the air. Or water. Or just our general 21st century American zeitgeist as we come to grips with how far we are from anything close to a “post-racial” dialogue. Whatever it is, 2018 is turning out to be the year for movies about racial code switching. It’s the common thread that links projects as disparate as the gonzo anti-capitalist satire of Sorry to Bother You, the stranger-than-fiction part-comedy, part-true crime thriller BlacKkKlansman, and the Black Lives Matter-inflected YA drama The Hate U Give. At the heart of each film is a black protagonist who, having mastered the art of speaking “white,” ultimately discovers its limits as a means of challenging society’s white-dominated power structure.

Then there’s Blindspotting, which puts its own unique spin on these themes and turns the concept of code switching on its head. The film presents a white guy, Miles (Rafael Casal), born and bred in Oakland, who raps, talks, and acts like a walking stereotype of the ’hood even as his best friend, Collin (Tony winner and now Spirit Award nominee Daveed Diggs), has to live with the real implications of being an actual black man with a criminal record. Despite these tensions, the bond between Collin and Miles feels genuine, reflecting the real-life friendship between Diggs and Casal...

As it happens, both men (who co-wrote the screenplay) are gifted rappers and spoken word poets, a talent they draw on throughout the movie as their characters’ way of connecting with each other and entertaining others. But the shadow looming over even their most affectionate and lighthearted exchanges is the fact that only Miles can have it both ways – be an honorary brotha without ever losing the protections or privileges of being white.

That’s not how Miles sees it, of course. Fixated on the gentrification of their town by white hipsters – which he perceives as a threat to his own street cred – he has to be practically dragged kicking and screaming to the recognition that the experience of being black doesn’t belong to him. The major turning point is an explosive argument between the two friends after hotheaded Miles almost lands Collin back in jail. Collin lays into Miles and lays out exactly how toxic he’s being in playing at being black, and how willfully blind he is to both the damage he’s already done and the danger he still poses to his friend. It’s a powerful scene, one of several in which Diggs effectively evokes the omnipresent fear and frustration of walking through life with a de facto target on one’s back. And in its wake, we see tentative signs that a chastened Miles may finally be starting to get it.

[MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD]

Spirit Award Best Actor nominee Daveed Diggs in "Blindspotting"

Spirit Award Best Actor nominee Daveed Diggs in "Blindspotting"

But it’s the movie's climactic final scene – just when we think we can breathe more easily – that hammers the message home. In a twist of fate, Collin and Miles, who work for a moving company, are dispatched to the house of a white cop (Ethan Embry) who Collin saw shoot and kill an unarmed black man one night. Collin, who’s been struggling with guilt over not coming forward and reporting what he saw, confronts the officer in his basement and holds him at gunpoint as he raps out the full measure of pain and anger of being a black man in a world where violence perpetually threatens to claim him and where a white cop’s life and word will inevitably be given greater weight than his own. Having said his piece, he drops the mic – or in this case, the gun – and leaves the officer unscathed except by his words, with the final parting shot: you are the killer, not me. The cop’s face shows that that bullet has hit home.

The scene might not work for everyone: too stylized, too dependent on coincidence, too much of a credulity stretch to believe that things would play out that way. Yet symbolically and emotionally, it’s the perfect capper to the ongoing dialectic between Collin and Miles, who’s also a silent witness to the verbal beatdown of the cop. These words, the language of being black, may only have limited power, but they are Collin’s – not the white men’s – they are all he’s got, and in that moment, they are enough to assert his right to be heard and treated with dignity. They’re also a warning that if his words aren’t heard and heeded, their only alternative is more violence. In that respect, Blindspotting, perhaps more than any of the other recent films addressing the problem we all (still) live with, may be the best distillation of our current moment. If BlacKkKlansman showed us the heavy weight of the past that’s still with us, while Sorry to Bother You showed our potential dystopian future, Blindspotting speaks to where we are now—with humor and anger, yes, but also with a glimmer of hope.

If you saw Blindspotting what did you think of the ending?