John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

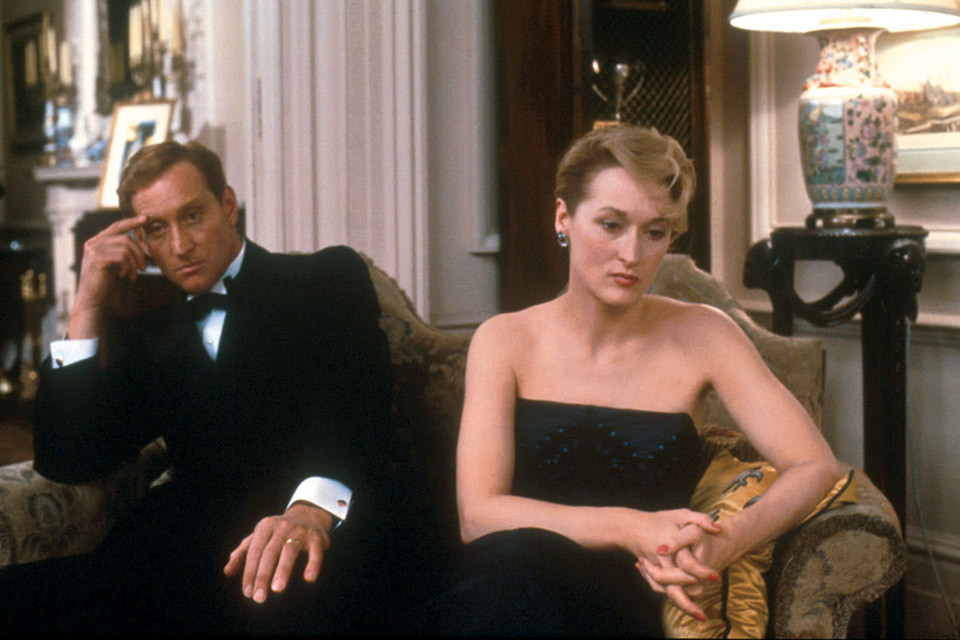

Charles Dance and Meryl Streep in "Plenty"

Charles Dance and Meryl Streep in "Plenty"

#11 — Susan Traherne, resistance fighter turned diplomat’s wife with a gnawing sense of unease about the life she must lead.

MATTHEW: “I just wish she were more ordinary,” a persnickety commercial director grumbles about an offscreen model hired to play the mother in a promo for dog food. “Will the audience identify?” he frets. We’re in England in the postwar 1940s and Susan Traherne, a former agent in the French resistance, is rolling her eyes through a mind-numbing advertising job that she will promptly vacate. The scene is quick but Susan walks out just in time for the director’s comments to resonate as a sly statement on the woman herself, the reliably erratic anti-heroine played by Meryl Streep in Fred Schepisi’s tepid cinematic adaptation of David Hare’s Plenty. Will an audience identify with a figure so brazenly, even coldly unconventional? And does such identification even really matter...?

Hare’s play first premiered in 1978 in the West End with the underrated Canadian actress Kate Nelligan in the lead as Susan, delivering a tour de force that later on Broadway inspired the New York Times’ Frank Rich to advise, “Only a fool would hold his breath waiting to see a better performance this season.” Plenty eventually made it to the screen in September of 1985 with Streep in tow. The film sets out to tell a story that is more complexly ambitious than the majority of Streep’s cinematic undertakings thus far — but that doesn’t necessarily make it a good film.

Plenty is a scattered inquiry into a highly-specific case of difficult womanhood, but the film itself is often a defective experience. Schepisi and Hare, who adapted his own work, have all the necessary ingredients for a daring and dynamic piece of cinema, one intriguingly centered around a fundamentally prickly persona, given life by a incomparable master of many guises. But the whole never coheres and, sadly, neither does Streep’s performance, which is neither an out-and-out catastrophe of miscasting (as in Still of the Night) nor a half-shaded interpretation of an already vague character (as in The French Lieutenant’s Woman). As Susan continually dislodges herself from different emotional planes and states of mind, Streep’s perpendicular posture and plummy accent, defined by cadences that are crisply studious but also unusually strained in a style only befitting the stage, remain the same. Other actors, including Charles Dance (as the low-level diplomat Susan will eventually marry) and Tracey Ullman (as her forthright confidante), seem in awe of Streep and arouse a cool, scowling remove in her own performance that doesn’t always suit this badly-behaved skeptic.

Plenty is a scattered inquiry into a highly-specific case of difficult womanhood, but the film itself is often a defective experience. Schepisi and Hare, who adapted his own work, have all the necessary ingredients for a daring and dynamic piece of cinema, one intriguingly centered around a fundamentally prickly persona, given life by a incomparable master of many guises. But the whole never coheres and, sadly, neither does Streep’s performance, which is neither an out-and-out catastrophe of miscasting (as in Still of the Night) nor a half-shaded interpretation of an already vague character (as in The French Lieutenant’s Woman). As Susan continually dislodges herself from different emotional planes and states of mind, Streep’s perpendicular posture and plummy accent, defined by cadences that are crisply studious but also unusually strained in a style only befitting the stage, remain the same. Other actors, including Charles Dance (as the low-level diplomat Susan will eventually marry) and Tracey Ullman (as her forthright confidante), seem in awe of Streep and arouse a cool, scowling remove in her own performance that doesn’t always suit this badly-behaved skeptic.

Streep, who has never looked lovelier, certainly erects a confident, put-together facade, but she never comfortably settles into the character. The performance improves in ways I’ll detail later, but I never lost the impression that a role like Susan requires a far more mysterious actress whose performative choices and emotional vulnerability are a little less evident. What say you?

JOHN: Color me surprised that when Meryl Streep-as-Susan Traherne utters, “I have a weakness — I like to lose control,” I sit hopelessly unconvinced. Because this late-film statement rings false to any viewer mindful of the glaring disconnect between the role’s requirements and the performance itself, Plenty stands as the ultimate failed test in Streep’s early career and a clear indication of her limitations. Meryl Streep can do anything... except possibly lose control. I don’t mean to come down harshly on Streep; Susan Traherne must read like a compelling role, and it’s not that the actress has proved herself entirely unable to self-destruct or walk the plank of emotional abandon before. But she gets little help from the filmmaking itself with its staggered time jumps, stagey wide frames, and dull cinematography. She sticks out like a sore New Jerseyan among her British costars. Still, I expected a major unraveling.

I commend Streep's refusal to soften this abrasive character, whether she's firing random gunshots at Sting or peeling off wallpaper or practically burning down the house at her husband’s dinner party. In quieter moments, Streep does manage a portrait of a woman bogged down by unfulfilled hopes and the banal realities of working at jobs well below her capabilities. But in Plenty her knack for emotional transparency becomes an odd fit for a role that requires high-wire concealment of an unnerving and ultimately disruptive well of sadness, the type of characterizations that actresses like Jessica Lange or Judy Davis frequently mastered during this era. We’re meant to believe that Susan’s post-resistance life continually clashes with her headstrong and volatile persona, but this spark noticeably flames out for a majority of Streep’s performance.

“I’m grateful for anything that’s got a little life in it,” Susan tells bohemian pal Tracey Ullman, who is both livelier and more convincingly British than Susan. I kept waiting for Susan to drop more vivid hints that she’s much too spirited for the life she leads, but Streep is often just too placid, dialling down when she might have had more luck dialling up. A majority of her performance floats in and out of different British inflections, her accent work noticeably overcompensating for her being the only American in this tony English cast. Most distressingly for the pedigree of the role and project, Plenty is one of the first times I actually felt bored by a Meryl Streep performance.

Thankfully, it's not an entire wash. If you forget about things like consistency or coherence, certain moments do impress. When Streep watches Sam Neill ride off to another post, she looks forlornly at both her short-lived romance and all the excitement that goes along with it in a wordless close-up perfectly suited to the role and her strengths. Midway through the film, Susan now finds herself working for Queen Elizabeth’s coronation committee. She trims her hair short, dresses like a Hitchcock blonde, and seems to be thriving in a career and milieu more suited to her supposedly voracious personality. In perhaps her best scene, Streep consigns Sting to have her child, meeting up with this acquaintance after years apart, with only a tenuous prior connection between them. Although single, Susan wants to be a mother and raise the child with her friend. “I don't see why I should compromise,” she says, steely and without a shred of naïveté. Streep and Sting share palpable chemistry in this seduction scene, even though Susan registers as a completely different character. Hare’s time jumps constantly undercut Streep’s character development, offering spare episodes for her to try her hand at without providing any conjoining links with which the actress might deepen Susan’s emotional progression. I suppose one could make a case that the spike in Susan’s depression coincides with her rise up the social ladder, but this doesn’t seem deliberate, much less probed.

What do you see as Streep’s greatest setbacks or triumphs in the part?

MATTHEW: Lange and especially Davis are particularly inspired recasting possibilities on your part, not least because they famously tend to paint in bold strokes; this technique might not necessarily expose anything deeper about Susan but it would at least make a more striking impression. Although I’ve watched Plenty only once, it’s clear to me why a more understated actress like Streep or an altogether gauzier one like Rachel Weisz, whose interpretation of Susan in the Public Theater’s 2016 revival was largely met with pans, might have a tougher go of making sense of this proud but elusive neurotic. If you had trouble buying “I like to lose control,” an arch, late-stage admittance that indeed only rings half-true, then I was even more baffled at the question Dance’s diplomat poses to Susan early on in the film: “You don’t think you wear your suffering a little heavily?”

Streep’s Susan doesn’t wear any emotion too heavily, mostly because the film’s infuriating ellipses make such concentrated, inward explorations all but impossible. That being said, I don’t think the performance is anywhere near a total wash, especially since Susan’s descent into mental illness unearths a more thrillingly unpredictable spirit that Streep cannot help but occasionally spark to, prompting small but significant ruptures in the character’s generally stolid exterior. She aces the breezy lustiness of the character, whose multiple dalliances make for some of the movie’s more engaging passages, particularly her almost-romance with Sam Neill’s dashing fellow fighter that bookends the film. I also admired the eerily sedated quality Streep brings to her scenes in Jordan, in which Susan is temporarily coaxed into playing the dutiful diplomat’s wife. She’s also great in a long, two-handed exchange with Ian McKellen, playing her husband’s superior, in which Streep bristles with white-hot exasperation at the latter’s haughty tactics of evasion.

Best of all, however, is an earlier, centerpiece dinner party sequence that finds a newly-married Susan needling another of her husband’s superiors (played by that notoriously subtle scene-stealer John Gielgud) with poised peacock pride over his (alleged) involvement in the Suez Canal Crisis. This ultimately gives way to a self-righteous monologue, shot in extended close-up, that becomes a contained performance unto itself, one that Streep deftly negotiates, her cerebral instincts a perfect fit for this crucial dressing-down.

Otherwise, I find little else that’s truly stirring in Susan Traherne, who could have ideally manifested as a freedom-fighting Mabel Longhetti with surer artists both in front of and behind the camera. This barely-coping sometimes-madwoman would have definitely benefited from a nervier interpreter. This quote, provided by Streep to on-set reporters, may help us understand why she's unusually tentative here:

“Playing a character as I am, who is uncompromising in the demands she makes on herself and on other people, I really have to come up to that challenge and it tests my mettle. When the stakes are so high, when everything is a matter of life or death, and you don’t know if you’re going to see each other the next day or not, or if there’s going to be a next day, I think that life has richness and things matter.”

Tracey Ullman and Meryl on the set of "Plenty"

Tracey Ullman and Meryl on the set of "Plenty"

Plenty certainly tests Streep’s mettle, but it also exposes a humbling quality about the actress that is perhaps best summarized by a pithy but profound quote from Philip Seymour Hoffman, taken as part of a larger statement: “Actors are responsible to the people we play.” Even at this somewhat early juncture in her career, it’s clear that Streep keenly understands this responsibility and feels indebted to her characters with an overwhelming urgency that sets actors like Streep and Hoffman apart from the herd. Streep displays a palpable respect for so many of her characters, as well as a fundamental need to honor their circumstances as best she can.

Here’s another quote from Streep, regarding Susan:

“I loved her anger and the size of it and her fearlessness in expressing it. And I also was attracted by the dream inside of her, and the idealism. To me, she seemed like someone who all through her life up to middle age just doesn’t stop being as altruistic as only teenagers are, and obnoxious about the purity of the world. I think we’ve seen a lot of heroes in literature and in drama, men who ask a lot of their circumstances, and of society and the world, and who are demanding, aggressively so. I don’t think that’s unusual; what I think is unusual is that it’s a woman.”

It’s easy to understand and appreciate Streep’s interest in Susan, a character so radical in conception that she shares DNA with everyone from the aforementioned Mabel Longhetti to A Doll’s House’s Nora, who, like Susan, also ends her journey by defiantly walking away from her marriage. But do you think Streep revered Susan’s iconoclasm too strongly to actually breach the barrier between actress and character, and thus playing a heroine when she should have been investigating the rougher, less sympathetic components of the character? What exactly is it about Susan that prevents Streep from inhabiting her with the sustained and immersed conviction endowed to, say, Joanna Kramer or Karen Silkwood? Can this all just be chalked up to bad writing and direction?

JOHN: The short answer might be yes? I don't necessarily see Streep actively pushing back against exploring Susan’s less tolerable attributes. It instead seems as though Hare’s episodic screenplay and Schepisi’s muted direction just didn’t facilitate the immersed conviction and rougher edges that the role requires. In those quotes you've pulled, it's clear that Streep relished the opportunity to create a warts-and-all protagonist who is both heroic and flawed. Perhaps she scales back her performance in a tactical move, refusing to slip into fits of madness so as not to diminish the struggles of this conflicted woman. While I do agree that the dinner scene is a highlight of her performance, I wonder if we appreciate it solely as a respite from the overarching boredom of much else that surrounds it, excusing the sheer lunacy of Susan’s imperviousness, which Streep slips on like a mask, untethered though it may be from what we have come to expect from the character. The scene just reminds me of how great Streep can be when she’s on, but I’ve already largely forgotten the specifics of either Susan or the scene’s circumstances, a pattern that has become apparent in discussing Plenty. Nearly every highlight from this performance has the effect of caffeine waking one up from a dull snooze, offering fleeting jolts of verve as well as recollections of what Streep can do but, for the most part, fails to do here. Maybe allowing the viewer to experience the dashed hopes and disappointment that Susan feels is the film’s ultimate achievement.

JOHN: The short answer might be yes? I don't necessarily see Streep actively pushing back against exploring Susan’s less tolerable attributes. It instead seems as though Hare’s episodic screenplay and Schepisi’s muted direction just didn’t facilitate the immersed conviction and rougher edges that the role requires. In those quotes you've pulled, it's clear that Streep relished the opportunity to create a warts-and-all protagonist who is both heroic and flawed. Perhaps she scales back her performance in a tactical move, refusing to slip into fits of madness so as not to diminish the struggles of this conflicted woman. While I do agree that the dinner scene is a highlight of her performance, I wonder if we appreciate it solely as a respite from the overarching boredom of much else that surrounds it, excusing the sheer lunacy of Susan’s imperviousness, which Streep slips on like a mask, untethered though it may be from what we have come to expect from the character. The scene just reminds me of how great Streep can be when she’s on, but I’ve already largely forgotten the specifics of either Susan or the scene’s circumstances, a pattern that has become apparent in discussing Plenty. Nearly every highlight from this performance has the effect of caffeine waking one up from a dull snooze, offering fleeting jolts of verve as well as recollections of what Streep can do but, for the most part, fails to do here. Maybe allowing the viewer to experience the dashed hopes and disappointment that Susan feels is the film’s ultimate achievement.

By the end, Susan remains in the abstract. I experienced a majority of the performance as Streep playing an idea about a woman, an era, and a country rather than giving life to a flesh-and-blood woman like so many other characters she's etched into being. It’s much more interesting to discuss Plenty in the theoretical — as there are only so many beatings this dead horse can withstand — and how it fits into the emerging patterns of Streep’s career. Susan Traherne joins the scores of difficult women that form Streep’s filmography and reinforces the key feminist thread that runs throughout most of her films during this period. In her quest to find high-quality literary roles that challenge both audience expectations and her own capabilities as an actress, Streep sometimes gambles on the pedigree of the project alone and produces lukewarm, affected, yet always well-intentioned efforts. At the height of her career, it’s telling how Streep refuses to sell herself short in bombastic blockbusters or exploitative sex thrillers or other meaningless drivel, choosing instead esteemed plays and books and the stimulating characters within them. This is what I will remember about Plenty, even though, as Susan admits, “I want to change everything but I don’t know how.”