"The Furniture" honors the Production Design of The Age of Innocence (1993) for its 25th anniversary year. The Martin Scorsese classic is newly available from the Criterion Collection. (Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.)

The final act of Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence leaps through time. The ever-roving camera comes to a temporary rest in the home of Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis), married to May (Winona Ryder) and entering the longue durée of family life. But this relative physical stasis comes with the sudden acceleration of time. Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker fast-forward through years of business, leisure and child-raising. After nearly two hours of social whirlpools and lingering formalities, suddenly it’s a new century.

But despite the speed of this sequence, it’s important to pay close attention. On the wall of Newland’s family home rests one very famous painting. Somehow, through the magic of cinema alone, our hero has ended up with JMW Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire.

It’s an icon for his last days, a masterpiece of a bygone era being towed away...

(You'll find the same metaphor in Skyfall, where there's no chance of missing it.)

The real Temeraire was never privately owned. It passed from Turner’s own home directly to the public museums of the United Kingdom. But in adaptation, neither faithfulness nor accuracy is a cardinal virtue.

And this classic of maritime art is but the flagship in a great armada of paintings used by the Oscar-nominated design team of The Age of Innocence, led by production designer Dante Ferretti, art director Speed Hopkins and set decorators Robert Franco and Amy Marshall. These artworks aren’t simply period decor, but active participants in an ever-engaged aesthetic conversation.

Often they echo their society. James Tissot’s Too Early hangs in the Beaufort mansion, an adornment and endorsement of the scene that takes place in front of it every year, on the night of the opera ball.

Mrs. Mingott (Miriam Margolyes), notorious for her independence and single-mindedness, has covered her walls with even more dogs than she can keep on her lap.

Some of the families weaponize their private collections, using portraits as unsubtle reminders of their heritage and station. I am pretty sure that the gigantic one in the middle was created especially for the film, but the smaller images around it are taken from real portraits of 18th century Dutch New York society matrons. The woman on the bottom-left is Catherine Van Rensselaer Schuyler, mother of Angelica, Eliza and Peggy.

These mansions sport the sigils New York’s historical mythology. The Hudson River School and its landscapes of Manifest Destiny are well-represented. An earlier piece of American Revolutionary propaganda, The Death of Jane McCrea, gets its own close-up.

But not everyone’s taste is quite so blunt. The Countess Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer) supports the avant-garde. In her home, tensions play out under the bizarre and watchful eyes of Caresses, a striking painting by Belgian symbolist Fernand Khnopff. Earlier on, Newland is fascinated by a faceless woman of Giovanni Fattori, one of Italy’s proto-Impressionist Macchiaioli.

Yet despite her more adventurous taste, the Countess is still very much part of this world. She cannot escape from its overstuffed decor and its endless visual pageantry. She, like everyone else, lives in a museum. The Archer mansion even includes a painting of more paintings, Samuel Morse’s The Gallery of the Louvre.

Everything about their lives is composed and arranged like a gallery of fine art. Mrs. Mingott chooses spoons from a collection catalog, as she might choose sculptures for a new wing.

Every plate of food is carefully arranged to highlight color and form. Meals are like a visit to the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia or the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, the tastes of the rich meticulously arranged by their eccentric sense of order.

After all, this is a generation whose most glamorous houses have now become actual museums. The ornate summer showcases of the Gilded Age still line the Hudson River and the cliffs of Newport, Rhode Island. Open to tourists, many are even publicly owned. Only the grand houses of Midtown Manhattan are actually gone, the mansions of 5th Avenue as forgotten as the old Metropolitan Opera on 39th St.

In their stead, we have this film. It is a living museum, though one which focuses on emotional and thematic accuracy over perfect visual faithfulness and period precision. It depicts a society that was a living museum in its own time, forever asking its patrons to take a step back from the velvet rope, to please not sit in that chair.

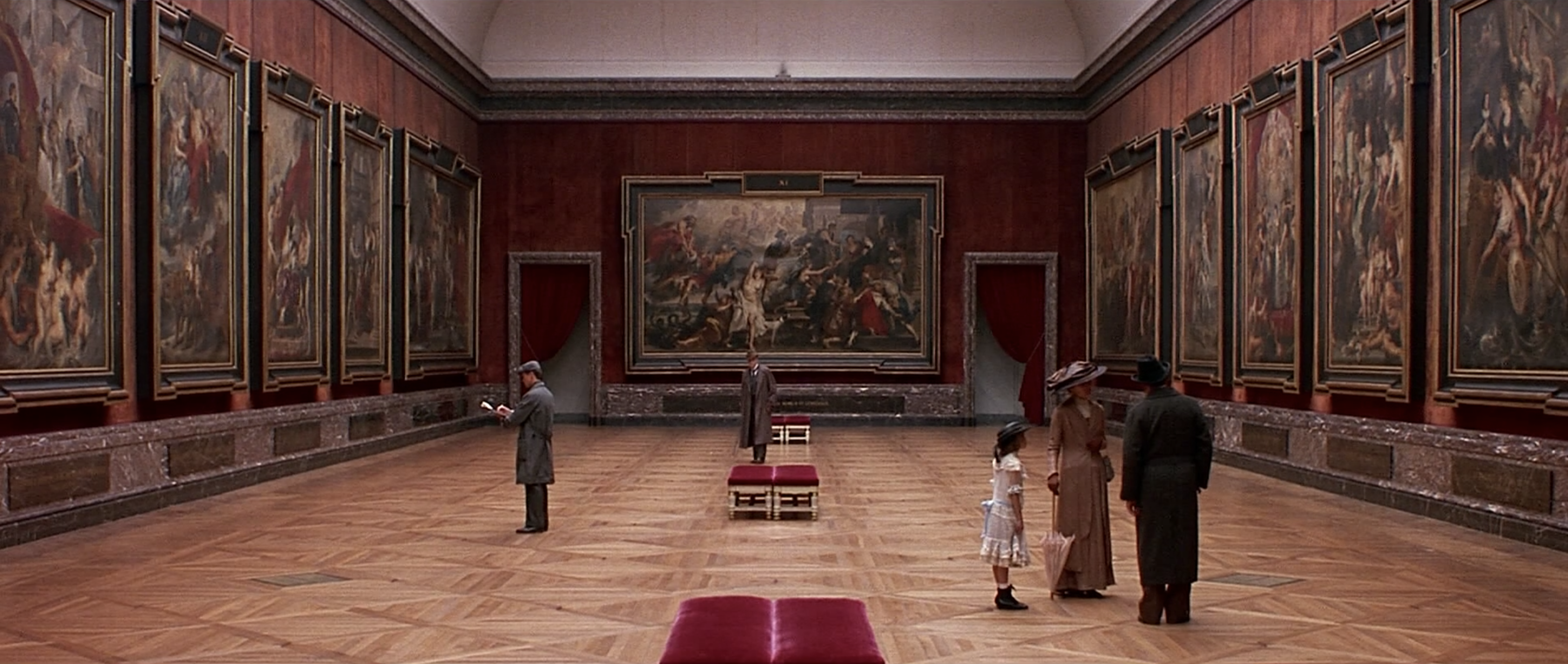

But eventually time marches forward, slowly pressing into the 20th century. At the twilight of the age, Scorsese follows Newland into his own exile, fleeing a new New York for the refuge of the Old World and its grandest museums. Once the Louvre was a painted curio in his own home. Now, at the end of a days, he becomes a curio in the Louvre.