By Glenn Dunks

As a medium, film is a record forever. An actor can give a stunning performance on a stage, but without a camera to capture it, it remains somewhat in the ether – a happening, an instance, a moment in time that can only truly live on in the mind of those who witnessed it. Of course, that doesn’t make it any less valid or worthy, but it’s something worth considering as we watch movies that they, even fictional ones, are ultimately a document of the emotions and the energy and the craft that was put into it, captured forever for anybody to experience.

As a medium, film is a record forever. An actor can give a stunning performance on a stage, but without a camera to capture it, it remains somewhat in the ether – a happening, an instance, a moment in time that can only truly live on in the mind of those who witnessed it. Of course, that doesn’t make it any less valid or worthy, but it’s something worth considering as we watch movies that they, even fictional ones, are ultimately a document of the emotions and the energy and the craft that was put into it, captured forever for anybody to experience.

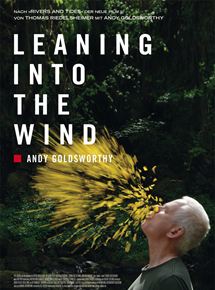

I thought of this as I watched Thomas Riedelsheimer’s Leaning into the Wind: Andy Goldsworthy because it is a film that will live on as the only document of some of Goldsworthy’s work. The artist is known predominantly for his works that incorporate nature and are often finite in their existence. Impermanent works of art such a strip of autumnal yellow leaves plastered onto a riverside boulder like papier-mäché only to blow away with a gust of wind through the valley; a silhouette of his own body on the pavement in the rainstorm that disappears, filled in my further falling rain, once he stands and walks away. Riedelsheimer’s film is then in some ways an essential work of film – although the very ephemeral nature of the artist’s work (there's not all that much to really say about some of them, you know?) when coupled with the very laid-back tone of the director (who’s also the cinematographer and editor) will make it harder for audiences to latch on to that a more traditional documentary.

Riedelsheimer’s camera follows Goldsworthy fifteen years after his earlier film, Rivers and Tides: Andy Goldsworthy Working with Time. I have not seen that film, but its legacy has persisted, perhaps most notably because of Roger Ebert’s four-star review in 2003 after becoming a word-of-mouth success some nine months earlier (it ranks as one of the 100 highest-grossing documentaries of all time despite playing no wider than 15 theatres over 81 weeks of release). A rare instance of a documentary sequel, it offers us an artist now in his 60s working alongside his adult daughter and if the non-fiction landscape has changed dramatically then I may hazard to guess from what I have seen that the man himself has not.

Goldsworthy’s work is at times both elaborate and simple. A gathering of sticks or a pile of rocks, the sort of things that likely hold great internalized meaning to the man who built them, but if happened upon by bushwalkers or tourists would no doubt be of little worth. Large boulders carved out to form a sort of coffin that he proceeds to lay in before walking away at which point they will become part of the landscape and be filled with rain and plantlife. We see glimpses of larger projects including one where rocks are split in half and placed a small distance apart like a tunnel, as if something struck the earth and split the land and everything in its path in two. A large tree branch is chainsawed with a sort of criss-cross pineapple pattern and then covered in clay before being moved into place from the rafters of what appears to be a disused church.

Fred Frith provides a hoppy jazz soundtrack that feels entire appropriate, never more so than when Goldsworthy climbs through a thicket of hedge plants. It’s something that for most would come off as a very special kind of pretentious, and yet here it strikes as something altogether philosophical. I’m not sure I believe all of the things that the man has to say, but where there is genuine purpose lies, I feel, genuine art. And that’s where a film such as Leaning Into the Wind plays such a vital role. Without the camera, these works – as frivolous as many of them may appear on initial glance – would vanish forever. Whether Goldsworthy cares or not, isn’t really the point, but I’d like to think that he does given he’s now allowed Riedelsheimer to do it twice.