John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

#10 —Molly Gilmore, a married woman who, against her better judgment, falls in love with a married man.

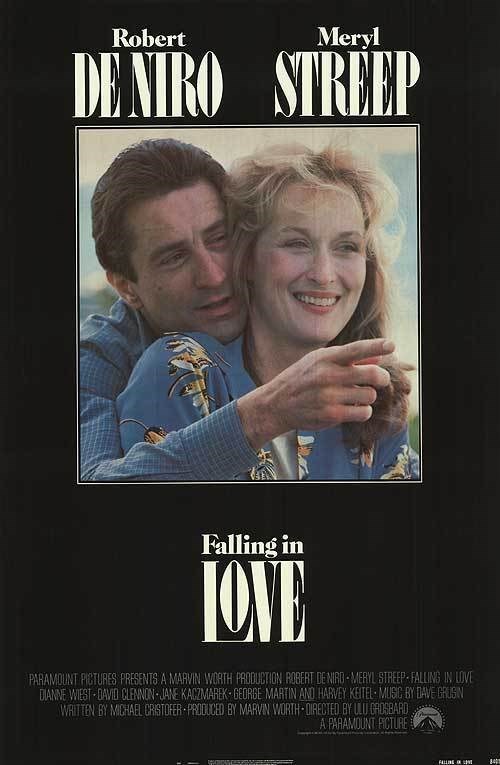

JOHN: Falling in Love is my favorite movie. Well, not exactly. I only just watched it for the first time, so I can’t exactly gauge the extent of my affection. But I’ll repeat: Falling in Love is my favorite movie. It’s hard not to fall in love (sorry) with a movie where Meryl Streep and Robert De Niro have an affair in 1983 New York City, aided by best pals Dianne Wiest and Harvey Keitel. After a chance encounter at the beautiful Manhattan bookstore Rizzoli on Christmas Eve, the two meet again months later, care of the blessed Metro North, and eventually have their desires and marriages tested. One could say it’s a Mazursky-inflected Deer Hunter reunion, minus the wit, or The Bridges of Dobbs Ferry, minus the tension. But Falling in Love is an almost lovingly clichéd brief encounter featuring two unexpectedly nuanced lead performances. It’s cinematic comfort food of the loveliest order.

Streep is Molly Gilmore, a graphic designer with a stiff doctor husband (David Clennon) and a dying father (George Martin), and nearly nothing else of a backstory to report. In our last entry I noted that Streep as Karen Silkwood is ostensibly the closest character to her own personality that she had yet played, but Falling in Love quickly bucks that distinction...

Character details of any sort are superfluous in describing Streep as Molly, as the film barely disguises the fact that both she and De Niro are playing themselves. This isn’t necessarily a demerit; they “play themselves” in the way that Kate and Spence did in their vehicles, and when you’re Meryl Streep and Robert De Niro, playing yourself can be just as appealing as other actors deeply camouflaging themselves into characters.

Streep is chic, present, constantly intrigued, deluged with emotions, full of non-sequiturs and facial tics, and effortlessly charismatic in a part as paper-thin as her character’s design portfolio. Rather than lament the imminent shortcomings of the role, I’d rather savor the time-capsule aspect of the project and all of the indelible Meryl Moments baked into it. There’s a standout scene very late into the film, in which Molly is actively betraying her marital vows and going through outfits to wear on her “date” with De Niro’s Frank Raftis. Streep looks at herself in the mirror and whispers, “What are you doing?” with an honesty as piercing as her Adaptation bathroom break.

Then there’s her initial, flustered response to De Niro’s early come-ons, where she responds to his “How are you?” with “I’m married, too.” and the delicious way she rationalizes their first official date with the spry line, “Well married people have to eat lunch, too.” What are some moments in which you fell in love with Meryl or the film? Did you fall in love? Or maybe you would care to answer the question De Niro poses to Keitel during a scene at the gym: “Do you think I’m good looking?”

MATTHEW: Oh Bobby, don’t know you’re perfect? I hold up Meryl and Robert as something like the familial heads of my film love, or at least my early fascination with film actors. What this really means is that I felt an overwhelming urge to scream “Mom and Dad!” like one of Sarah Paulson’s Twitter stans throughout the entirety of Falling in Love, a film experience that’s a bit like watching home video footage of your very famous parents getting together while pretending they aren’t legends. (Look closely at the film’s numerous street scenes and you can clearly see crowds of people gathered on corners and packed near buildings to watch the production, i.e. De Niro and Streep.)

Helmed by the wonderful screen and stage director Ulu Grosbard, who wouldn’t make another film until 1995’s phenomenal and masterfully-acted Georgia, Falling in Love often plays, quite charmingly but also quite unevenly, like a Nora Ephron-scripted remake of Brief Encounter. When held up against Streep’s projects thus far, it’s harder for me this time around to imagine what life might be like for Molly and Frank off-screen, away from each other. Their backstories, such as they are, feel like explanatory, writerly constructs. Both actors are roped into selling behavioral traits we just don’t believe, like Streep’s manic outfit-changes or De Niro’s verbal rehearsals of his conversational come-ons. And their spouses (including a good Jane Kackzmarek as De Niro’s quietly watchful and wounded wife) are far too sidelined for the stakes to ever feel equal. So yes, this is certainly a slimmer endeavor than these two performers usually embarked on at this untouchable stage in their careers. And yes, it is a bit jarring to see two acting heavyweights engaged in a light, middlebrow entertainment that often verges on romantic comedy, clumsy meet-cute and all. But neither Streep nor De Niro are coasting in roles that aren’t entirely as tailor-made for them as I had expected.

Dianne Wiest co-stars in only her fifth movie.

Dianne Wiest co-stars in only her fifth movie.

At the start, Molly seems to be playing one of those brainy, attentive, good-humored women who we might inevitably assume to be close to Streep’s actual personality. She glides through the streets and stores of Manhattan with a smooth yet determined grace that you just know is Meryl’s actual walking style. She introduces a giggling and immediately credible rapport with her serially self-deprecating best friend, who, once again, is played by DIANNE WIEST. And she peels an orange in a charmingly weird way that I won’t bother to describe, but suffice it to say that you wouldn’t believe any of this were it not Streep doing it with her signature, casual conviction.

But I don’t think Streep is actually playing herself, as you earlier suggested. Molly is ultimately a character who’s sadder and more transparently conflicted than the buoyantly resilient real-world persona that Streep exudes. That’s how the character is written but it’s also the persona that Streep creates, using details like her husband’s inattention, her father’s sickness, and the recent loss of a newborn to build up a reserve of aggression, anxiety, grief, and yearning. One of the most interesting moments in her performance also proves to be one of the most incidental in the script, a fleeting line of dialogue about how Molly’s mother never appreciated the flowers she brought her during her infirmity nor, it seems, Molly herself. This tough-loving mother is never mentioned in the script again, but Streep’s reading of the line really honors its implicit history. She doesn’t just toss it off or turn it into a passive-aggressive aside, but lingers on it, plumbing the depths of this bitterness and never allowing us to forget this sizable chip on Molly’s shoulder.

But let’s get back to the film’s central relationship. What do you make of Streep’s intrapersonal performance with De Niro, especially with the memory of “Oh, Michael!” still fresh and unfading in our heads?

JOHN: Maybe Streep’s not exactly playing herself (and how could we plebeians ever truly determine that?) but is instead asked more simply to be than to transform via an accent, wig, or self-immersion within a different time period. The dull husband, dying father, and miscarriage beats didn’t exactly color the character for me as they did for you, maybe because each problem feels patently scripted as obstacles ripped from a Screenwriting 101 book. Like you’ve said, all I could think about was Streep and De Niro reuniting in this atypical project for stars of their abilities and stature. I assume that the two both jumped at the opportunity to work together again, regardless of the material, and this enthusiasm steadies shakier moments and deepens banal exercises like their first train-ride chatter. Although I just watched Falling in Love, few moments actually stick in my mind, but the ones that do are not textual or narrative, but are instead the lovely interactions, glances, and moments of trepidations between Molly and Frank.

But some moments land all their own. As much I was thinking about The Deer Hunter, I was also reminded of The Bridges of Madison County. Towards the end of the film, when both De Niro and Streep’s spouses are aware of their infidelities, Frank calls Molly and asks to say a final goodbye before he boards a plane to start anew in Texas. Streep seizes this opportune moment to be characteristically flustered, flaunting that visceral blend of intrigue and caution. She rushes past her husband, barrels into her car, and drives through a thunderstorm (of course) to say one final goodbye, just missing a railroad collision in her frenzied trek to De Niro’s home before ultimately turning back. Streep will later repeat this late-stage scenario of romantic decision-making in a vehicle during the rain, but this is a fine warm-up, offering her a rich opportunity to play the type of wordless negotiation and vacillation with which she excels in expressing. This tug between pragmatism and desire works as a summative statement for many a Streep performance, tempered here only by the vagueness of the character and the weightlessness of her conundrum.

Which other scenes left a mark on your memory? Or did it already evaporate?

MATTHEW: Arguably the film’s most heightened scene, is also the one that feels ripped from a completely different movie: Streep’s sobbing, knee-buckling breakdown at the cemetery following the death of her father, a moment that veers between being bizarrely overworked and genuinely heartbreaking as the actress performs at a strength perhaps more intense than the film can understandably handle.

That being said, I agree with you that the real achievements of Streep and De Niro’s performances here are those modest gesticulative touches that occur in between moments. With her vivid assortment of averted gazes, nervous pauses, and uncomfortable fidgets, Streep looks to be believably wading through inchoate feelings, clearly understanding the emotional vulnerability of a new and unplanned love that cannot be put into words just yet. For his part, De Niro movingly mirrors and smartly pushes back against Streep’s recessive tendencies, even as the latter remains the more glaringly shame-ridden of the two. It’s clear from the start that Molly is palpably attracted to Frank, but Streep never allows herself to look too comfortable or at home in De Niro’s company, reminding us of the inescapable difficulty of this inconvenient affair and making her sporadic flashes of contentment all the more meaningful. I never believed Molly as a fully-realized character but I believed the emotional journey that Streep had charted for her. More than anyone else involved in the production, she possesses a clear vision of what this distressed woman’s sensitivity might look like, how it might manifest itself not just internally but on her face and frame.

Falling in Love never threatens to break into the upper ranks of Streep’s filmography and the performance itself is easy to overlook amid a canon of ten performances already replete with some landmark characterizations. But as slight as the film may be, Streep is still able to impart a sense of individual experience, giving us a quietly potent impression of what it’s like to be alive right now as this particular woman. Sometimes that, combined with the ancillary pleasures of two peerless artists simply sharing the same screen, is enough.

Falling in Love never threatens to break into the upper ranks of Streep’s filmography and the performance itself is easy to overlook amid a canon of ten performances already replete with some landmark characterizations. But as slight as the film may be, Streep is still able to impart a sense of individual experience, giving us a quietly potent impression of what it’s like to be alive right now as this particular woman. Sometimes that, combined with the ancillary pleasures of two peerless artists simply sharing the same screen, is enough.