John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

#17 —Suzanne Vale, a recovering drug addict and B-list actress of royal Hollywood pedigree.

MATTHEW: It has always been impossible to escape the metatextual associations of Carrie Fisher’s Postcards from the Edge, which really means it has always been impossible to escape the shared history of two artists: Fisher and her famous mother, Debbie Reynolds, a relationship that is the very bedrock of Fisher’s 1987 novel and Mike Nichols’ subsequent screen adaptation. To watch the latter now, in a world without Fisher or Reynolds, is an experience of unavoidable and indescribable bittersweetness. It helps, however, that Fisher confronted even the most harrowing episodes of her lifelong addiction with a sly, battle-ready smirk and a tart tongue, which always ensured that she — and she alone — would get the last word. On the screen, Postcards from the Edge remains a salty, joyous, yet tough-minded immersion within the rocky recovery of its Fisher-like heroine, Suzanne Vale, and a prickly heartwarmer that continually confuses our inclinations towards laughter or tears.

This is largely because of Fisher, whose hysterical one-liners are an art form unto themselves. Consider, for a moment, that such gems as “Do you always talk in bumper stickers?” and “Instant gratification takes too long” and “What am I supposed to do, go to a halfway house for wayward SAG actors?” are all spoken within the first 20 minutes of the movie, and there are plenty more where those came from...

Meryl, Debbie, Shirley, and Carrie

Meryl, Debbie, Shirley, and Carrie

But there’s also Nichols, whose consummate, character-serving direction is a cozily ideal fit for Fisher’s condensed narrative, and the great Michael Ballhaus, who shot the film with sharp, sunshiny aplomb in the same year as Goodfellas. And then, of course, there’s the masterful Meryl Streep, who honorably served as Fisher’s on-screen avatar, shaking up her own tragedian persona in one of her all time most dexterous and rewarding comic outings.

In contrast to her marvelous performances in murky and tonally-dissimilar films like Ironweed or A Cry in the Dark or even her finest, pre-Postcards comedic turn in The Seduction of Joe Tynan, the genius of Streep’s work here isn’t hard to pin down in the slightest. Only Streep could take a screen figure as fraught with complications (and clichés) as the female addict and make her desires, motivations, and complexities as clear as a bell. In inhabiting Suzanne, Streep smartly subdues herself, hiding behind the sarcasm of Fisher’s redoubtable quips and eschewing the twitches, scratches, and other outsized theatrics that are the banner of addict performances. This isn’t to say that one approach is more valid than the other; there is as much difficult insight and honest-to-God emotion in Streep’s Suzanne Vale as there is in Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Sadie Flood or Anne Hathaway’s Kym. But down-to-earth understatement is so seldom applauded in these types of interpretations, which makes Streep’s subtlety not just a rarity but a key component in her completely plausible depiction of the artist/addict’s recuperation, in all its turmoil and tedium.

In contrast to her marvelous performances in murky and tonally-dissimilar films like Ironweed or A Cry in the Dark or even her finest, pre-Postcards comedic turn in The Seduction of Joe Tynan, the genius of Streep’s work here isn’t hard to pin down in the slightest. Only Streep could take a screen figure as fraught with complications (and clichés) as the female addict and make her desires, motivations, and complexities as clear as a bell. In inhabiting Suzanne, Streep smartly subdues herself, hiding behind the sarcasm of Fisher’s redoubtable quips and eschewing the twitches, scratches, and other outsized theatrics that are the banner of addict performances. This isn’t to say that one approach is more valid than the other; there is as much difficult insight and honest-to-God emotion in Streep’s Suzanne Vale as there is in Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Sadie Flood or Anne Hathaway’s Kym. But down-to-earth understatement is so seldom applauded in these types of interpretations, which makes Streep’s subtlety not just a rarity but a key component in her completely plausible depiction of the artist/addict’s recuperation, in all its turmoil and tedium.

Streep credibly adopts all the coping behaviors of the convalescing addict, from Suzanne’s marathon snacking and soda-guzzling (habits that Streep makes utterly mesmerizing, especially when skulking around the set of the cheapo-budgeted cop movie that Suzanne is working on) to the sheer physical restlessness that Streep doesn’t so much highlight as simply and unfussily embody. There is so much more to truly and repeatedly savor in this star turn, which is one of my all-time Streep favorites, but I’ll give you a chance to explain what it is that you relish about Streep’s Suzanne Vale.

JOHN: Have you ever seen this clip of Meryl praising Liza Minnelli? While recounting her experience of seeing Minnelli perform on Broadway in The Act in 1978, Streep remarks that after years of doing wild, outsized, and unrealistic theater at Yale, yearning for kitchen-sink-type roles, it was seeing Minnelli, a forthcoming, theatrical, and undoubtedly gutsy performer, that crystallized her goals as an actress. “That’s the kind of actress I want to be,” she says, “I want to have it rooted in reality, heart, soul, and true emotion, and I want it to be big." Minnelli’s outsized performativity actually finds a perfect avatar in Shirley MacLaine’s ecstatic and ebullient Doris Mann, and I’m hard-pressed to name a more honest and grounded Hollywood figure than Carrie Fisher. Together, these forces provide Streep with an ideal playground for the type of cherished and invigorating character-building she craves. Postcards, as ever, is a testament to her magnificent knack for going “big” while maintaining a startlingly authentic display of true heart and emotion, combined here with that utterly Streepian way in which she manages to come across as both relatable and preternatural.

My love for Postcards is so uncomplicated, so crystal clear. Suzanne Vale is one of those rare pristine performances in which everything just works; from her expert comedic timing to her barely-concealed sorrow to her vexed maternal relationship to those sublime musical numbers to her clever self-awareness that runs through this poignant and comic film, Streep’s performance is a marvel. I take your point about how this addict is atypically restrained, but notice how Streep’s oft-ridiculed penchant for small gestures (face touching, hair-playing, the way she ambles through some line-readings) gets reworked into Suzanne’s restless spirit, an ideal coalescence of actorly trademarks and character-specific details. As she awakens from her blackout and comes to find herself checked into rehab, Streep cycles through shock, confusion, dismay, and acceptance in an expressive but decidedly non-histrionic register, both amazed and slightly terrified to have landed at this stage of her addiction. Later on, while strapped to a cactus, hanging off the side of a building, receiving news that her business manager split town, Streep brilliantly underplays the drama both on set and off, but never at the expense of her whip-smart comic sensibility.

To appease her mother at the homecoming surprise party thrown in her honor, Suzanne sings a tune for their guests, a rendition of Ray Charles’ “You Don’t Know Me.” Turning slowly outward from the piano to face the crowd, Streep’s light and summery voice admits, “Anyone can tell, you think you know me well, but you don’t know me.” Doris urges Suzanne, adrift in her own head, to remove her jacket, a request she swiftly honors before hitting those strenuous high notes. Finally, she dials it down and almost looks straight into the camera’s eyes before softly, soberly declaring, “No, you don’t know me.” This is the moment where Meryl Streep — chameleon extraordinaire of her generation — closes some kind of curtain, all the while acknowledging the withdrawn or detached facets of her star persona. It’s hard not to also read certain criticisms of Suzanne as purposeful allusions to criticism of Streep herself. After only two minutes of screen time, producers berate Suzanne for not having enough fun, accusing her of holding something back. Suzanne overhears a seamstress complain about her shapeless breasts and sliding kneecaps, an unsubtle quip that parallels Streep’s own experiences with aging in Hollywood. (Streep hit 40 during production.) How do you read these allusions to Streep’s own career? What else should we take time to savor about Suzanne?

MATTHEW: We would be remiss not to lavish some more attention on the deliriously divine Shirley MacLaine, whose lack of a Best Supporting Actress nomination in 1990 is outrageous. MacLaine proves to be one of Streep’s most inspired scene partners, whether in everyday verbal exchanges that, from their mouths, become hilariously high-speed games of comic badinage or fight scenes in which every dredged-up detail of this mother-daughter duo’s contentious past is made equally acute and affecting by the pair’s itchy discomfort and palpable love. In terms of meta connections to Streep’s own career, I’m most struck by the showstopper that follows Streep’s ambivalent Ray Charles solo: MacLaine’s personalized rendition of Stephen Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here,” complete with reworked lyrics and piano-hopping choreography. The scene is a wonder because it works entirely against our initial expectations: Suzanne, who has before now treated her mother as little more than a necessary burden, radiates pure joy in watching Doris’ spotlight-stealing performance, while still utilizing one cannily-played close-up to show us Suzanne considering her mother’s hard-won survivalism, openly wondering why she lacks it and, perhaps, if it isn’t too late to acquire it and save herself. But you could also interpret this scene as Streep, who spent the near-entirety of the 1980s playing tormented, often solemn sufferers in projects devoid of joy, watching MacLaine, as colorful and consummate a crafter of larger-than-life characters as Minnelli or any actress, and once again recognizing the sort of kookily-inclined but endearingly big-hearted actress she might like to be and would arguably become in the years to follow.

However, this isn’t a one-sided acting partnership: Streep’s tactful reserve invisibly guides the occasionally overwhelming MacLaine towards some of the most introspective work of her career, including an early morning quarrel in which a sozzled Doris lays into Suzanne for worrying her by returning home late. Rather than dig through her treasure-chest of expressions and gesticulations, MacLaine barely moves a muscle, making her withering put-downs all the more devastating since they seem to manifest with relative ease. She meets Streep, who steadily expresses Suzanne’s growing offense and utter exhaustion during this exchange, on her own muted level, conveying a reciprocative relationship with her co-star that can be warmly felt even when their on-screen counterparts are at loggerheads. Similarly, Streep can evidently run circles around the tantalizing Dennis Quaid, playing a starlet-fucking himbo who seduces Suzanne against her better judgment, while still being an active and attuned presence in the scenes they share. Though her looks, talents, and sobriety are continually denigrated and underestimated by loved ones and ambiguous industry lightweights alike, Suzanne’s cleverness remains sharper than that of everyone who circles her, which is surely an accurate reflection of what it must have been like for Fisher to wander through Hollywood, wielding her cutting wit against those who sought to humiliate her with their knowledge of her own personal travails.

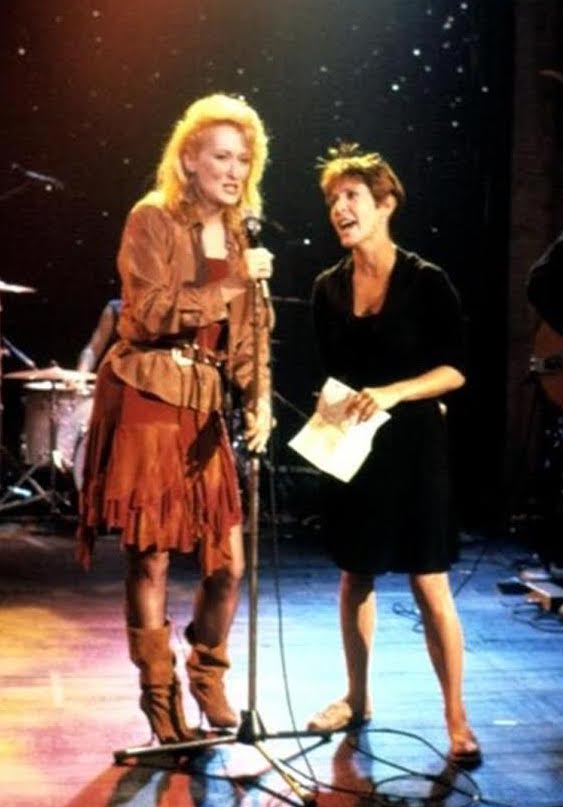

But Streep doesn’t lord this characteristic intelligence over her co-stars or the film; her Suzanne doesn’t come across as remotely primed for battle. Instead, Streep embraces Fisher’s gutsy, caustic spirit by physically making it her own, letting it seep into every fiber of her being, from her narrow-lidded, eagle-eyed stare to her swaggering, full-bodied strut. Contrary to her own suggestions, Suzanne does indeed possess many sides and Streep accordingly traces Fisher’s heroic character arc without foregrounding heroism or any one trait. There’s a casual pliability to Streep’s scaled-back method, an openness to different feelings and effects, that allows Fisher to place Suzanne in a variety of emotionally-disparate scenarios that come across less like writerly constructs than believable stops on the embattled journey of a weary woman. Streep connects the dots in Fisher’s narratively-lax script that a lesser actress might have left detached. Take for instance that beautiful looping scene in which Suzanne nails her flubbed line in just three takes. With her face bare and defenses down, Streep appears so humbled by the bitter but heartfelt wisdom of Gene Hackman (perfectly-cast as a tough-love director who emerges as the rare industry representative willing to discipline and aid Suzanne), as well as her own ability to still surprise herself and get the job done. This rare instance of professional gratification paves the way for the mother-daughter reconciliation that follows as Suzanne lifts Doris back on her feet after the latter gets into a drunken fender-bender. Sitting in a hospital room with her distraught mother, Suzanne sings a healing song from her childhood as she gently re-applies her mother’s eyelashes, a moment of ineffable tenderness that is also a gorgeous testament to the generosity of love, no matter its discontents. This generosity seeps through all of Postcards, from Suzanne basking in her mother’s musicality to that scene’s mirror image, in which Doris watches from on high as Suzanne finally seizes her own spotlight in the film’s country-western finale, at long last exhilarated by the unearthed talents of the survivor she brought into the world.

JOHN: Postcards from the Edge was the highest-grossing film on its opening weekend back in September 1990 and earned Streep her ninth Academy Award nomination, almost completely erasing She-Devil from memory as Streep proved her undeniable comedic chops in a bona-fide hit. Postcards also marks the beginning of Streep’s brief stint as a Los Angeles resident, which stretches from here to about 1994, after which she moved back east to Connecticut. Perhaps after actually getting through the Los Angeles Years we can properly survey this short and interesting period of Streep’s career. Instead, let’s luxuriate in this present and savor the reckless and shrewd, vulnerable and sturdy, exquisitely honest Suzanne Vale, still surviving and still here.

JOHN: Postcards from the Edge was the highest-grossing film on its opening weekend back in September 1990 and earned Streep her ninth Academy Award nomination, almost completely erasing She-Devil from memory as Streep proved her undeniable comedic chops in a bona-fide hit. Postcards also marks the beginning of Streep’s brief stint as a Los Angeles resident, which stretches from here to about 1994, after which she moved back east to Connecticut. Perhaps after actually getting through the Los Angeles Years we can properly survey this short and interesting period of Streep’s career. Instead, let’s luxuriate in this present and savor the reckless and shrewd, vulnerable and sturdy, exquisitely honest Suzanne Vale, still surviving and still here.