John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

#20 —Clara del Valle Trueba, paranormal matriarch of a prosperous South American family.

JOHN: Yes, paranormal. But please, take your expectations about Meryl Streep as psychic (and Glenn Close as her scorned, sexually repressed sister-in-law) that may be levitating midair and place them firmly on the ground. Actually, go ahead and place them below the Earth’s surface, and then you might be ready to endure one of the absolute worst films Streep has ever been caught in. The House of the Spirits, an adaptation of Isabel Allende’s titular novel, chronicles the tumultuous history of the Trueba family, a prosperous South American dynasty headed by Esteban Trueba (Jeremy Irons), a peasant turned plantation owner turned conservative senator, who marries Clara del Valle (Streep), the youngest daughter of a wealthy, liberal family, and did I mention that she can move things with her mind and predict the future?

While the exact South American country is never explicitly mentioned in either the novel nor film, Allende is herself Chilean and the political upheavals she recounts closely parallel those of Chile. Egregious casting of British and North American actors is almost the least of this film’s problems as The House of the Spirits quickly becomes a step-by-step guide to horribly adapting a treasured novel, dulling and deflating all traces of Allende’s elegance, insight, or political import. By the time Clara dies, I spent the last half hour daydreaming about all the novels I could (and should) have used that time to read, Allende’s especially.

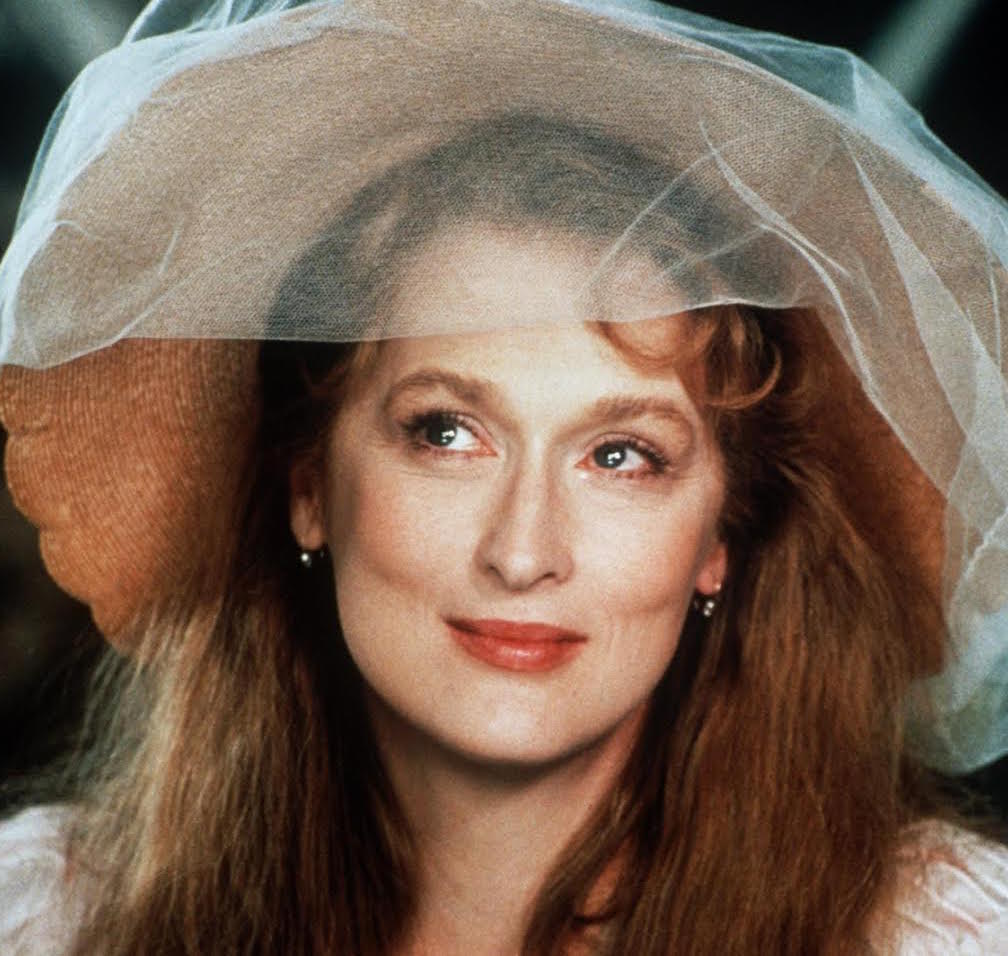

Streep, unfortunately, is Clara, a telekinetic clairvoyant with neither Carrie White’s range nor Raven-Symoné’s personality. After failing to stop the death of her sister as a young girl, Clara goes mute for years, a spell that finally ceases when she blurts out an ecstatic “Yes!” to Esteban’s marriage proposal. (Girl, you can see the future, but can you see the oaf right in front of your eyes?) Clara is a character stuck in the symbolic, intended to represent otherworldly love and timeworn wisdom, but Streep never brings this woman to life, barely registering at all as a character with distinctive traits. The extent of Clara’s telekinetic abilities are contained in just a few laughable vignettes, like when, after her marriage to Esteban, she levitates a table in their honeymoon suite, and he barks at her to “Put that table down!” Her psychic powers are conveniently deployed when the plot’s engine needs some juicing and are almost forgotten thereafter. Elaborately clad in white, full of ponderous glances, silenced by Esteban and seemingly unacknowledged by the rest of her family, Clara is ultimately an elusive figure, unilluminated by Streep’s uncharacteristically dull and wooden performance. Is there really any other way to spin this bombastic film and lifeless performance? What on Earth could have drawn Streep to this utter wisp of a part?

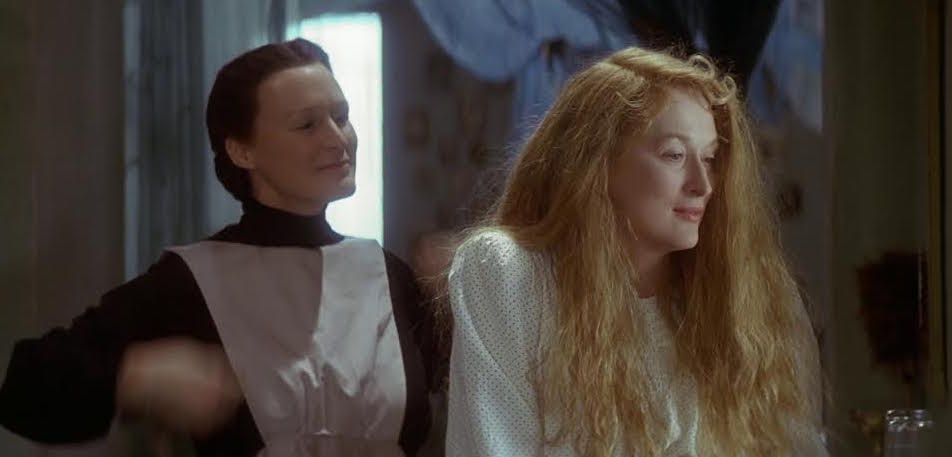

Reunited with her French Lieutenant's Woman co-star

Reunited with her French Lieutenant's Woman co-star

MATTHEW: The draw surely must have been director-adapter Bille August, whose Pelle the Conqueror won the foreign-language Oscar in 1987 and whose Bergman heritage picture The Best Intentions (scripted by Bergman himself) won Pernilla August an acting prize at Cannes the year before this project. But House of the Spirits is ultimately the kind of terrible, horrible, no good, very bad movie whose sheer awfulness sours the mood of anyone masochistic enough to endure this inexplicably whitewashed tale of Latin American empires. Where do I even begin? There’s the ensemble, each member about twenty years too old for his or her role in the film’s early stages and in turn aping at youth and vandalizing their carefully-crafted screen personas in the process. There’s the unspeakably and singularly atrocious lead performance by Irons, who is laughably aged-down (and rendered “Latino”) with a prosthetic nose and false teeth that are egregious offenses unto themselves. There’s Close, wearing colored contacts and doing a poor man’s Mrs. Danvers in a scenery-hungry turn that seems aimed at a Best Supporting Actress Oscar but deserves nothing more than a freshly-polished Razzie. There’s Winona Ryder playing the only progeny of Irons and Streep and providing the film with a stodgy, running narration that makes the actress sound like a bored AP English student reading aloud in class from a novel she only knows through Sparknotes.

August’s larger casting decision is a disgrace that would have probably buried his career had this film been made in the Twitter age. That being said, Streep’s casting makes some sense: Clara is, after all, a woman of amazing powers that are highly coveted but also unmistakably set her apart. The character has no profundity to speak of, but Streep doesn’t embarrass herself like Close or Irons because her playing, even in the piece’s most hideously melodramatic passages, retains a level of unshowy modesty, as if receding from the narrative might somehow simultaneously distance herself from this bastardized project altogether.

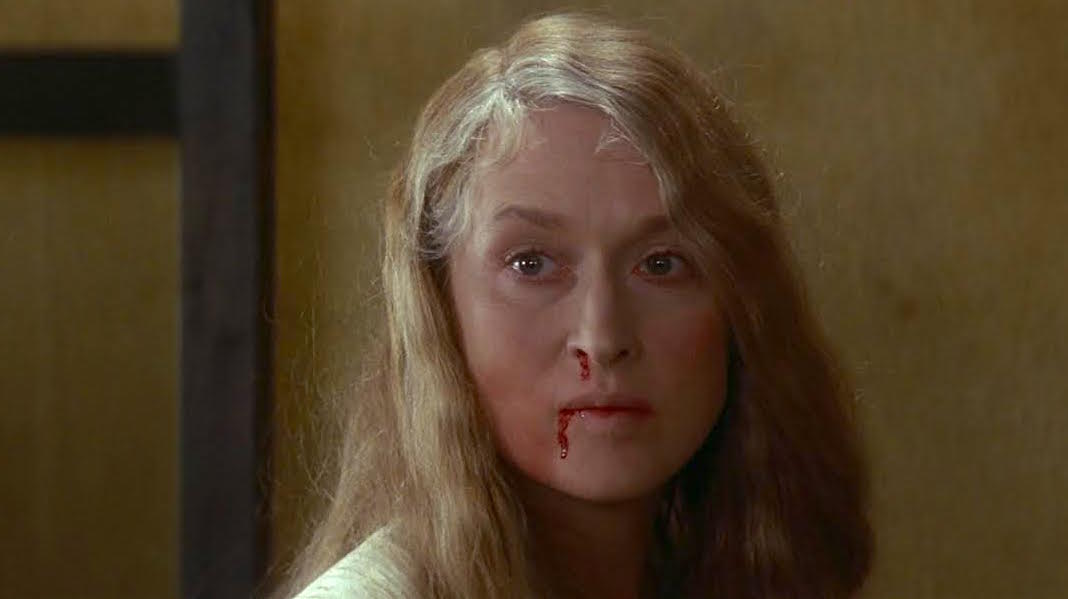

Streep’s knack for emotional transparency within particularized personas doesn’t necessarily fail her here because it’s not really solicited in the first place. August only needs Streep for her gauzy beauty in the early passages and then her somber, weeping nobility in the film’s halting latter half before finally calling upon her to embody a soothingly angelic apparition in her final scenes.

There’s nothing worth savoring much less saving in this performance, but the sincerity of Streep’s approach continually asks us to take these fragmented scenes seriously, but it’s a mostly futile request. If I’m being generous, there are a few instances in which Streep rises above the rubbish, if only for a nanosecond, like the moment in which August lingers on Streep’s transmogrifying face as Clara receives a message from The Beyond, a shot that holds our interest if only for its relative slowness, a rarity within this rushed and risible case study of how not to adapt a novel for the big screen. Streep also fares well in a reassuring mother-daughter bedroom conversation with Ryder, but everything the actress does here has already been achieved by her with more certainty and credibility on prior occasions. She distills the character into blanched displays of maternal concern and sage dotage, neither of which resonate in or after the moment. Streep can’t salvage anything in this ambitious but abominable production that simply doesn’t deserve Streep, whose unfailing conviction is so awkwardly applied in this wisp of a role. Why do you think Streep came onboard this sinking vessel? And do you find it symptomatic of what some might categorize as Streep’s arguably career-long problem of proper role-picking?

JOHN: I too must confess that I simply stopped caring about what was happening on screen after its mediocrity became so overwhelming, and perhaps Streep doesn’t deserve our utter indifference. When she appeared on screen, my ears at least perked up a bit, but there is nothing especially revelatory about Streep’s abilities in The House of the Spirits, nothing that she hasn’t done before and better. My “favorite” moment from her performance is undoubtedly her shutdown of Esteban at the dinner table, but even this feels more like a sporadic, wish-fulfilled outburst, an abrupt detour from Clara’s otherwise tranquil and unassuming demeanor. On paper, The House of the Spirits and Clara might seem like good ideas, but, in actuality, only result in a vague performance and an incompetent, bloated film.

JOHN: I too must confess that I simply stopped caring about what was happening on screen after its mediocrity became so overwhelming, and perhaps Streep doesn’t deserve our utter indifference. When she appeared on screen, my ears at least perked up a bit, but there is nothing especially revelatory about Streep’s abilities in The House of the Spirits, nothing that she hasn’t done before and better. My “favorite” moment from her performance is undoubtedly her shutdown of Esteban at the dinner table, but even this feels more like a sporadic, wish-fulfilled outburst, an abrupt detour from Clara’s otherwise tranquil and unassuming demeanor. On paper, The House of the Spirits and Clara might seem like good ideas, but, in actuality, only result in a vague performance and an incompetent, bloated film.

“Better on paper” is a rather apt descriptor of many a Streep project, as it describes both the sounds-promising-but-turns-out-bad quality of many of the actress’ films, their often literary origins, and the pedigree of either director or role that fails to kindle when the camera starts rolling. Many such failures point to the inherently difficult task of adapting novels into films; an act of translating literary grammar to rich visual and aural experiences, preserving the characterizations and points of view of great literature while also utilizing the possibilities of cinema. I ultimately wish Streep made better choices about which adaptations she pursued, perhaps privileging the artistic vision of the director and creative team instead of the relevance or importance of the source material itself.

How about you, reader? Have you seen The House of the Spirits?