by Glenn Dunks

Peak television! One could argue that unlike film, television only grows and grows in stature as the more resources and money are thrown its way. Whether you’re part of the small screen migration or still prefer things big and silver, it is hard to deny the impact that has occurred and the major cultural and structural shift that has forced its creators to tap into new and exciting takes on the form and storytelling more generally. I don't think anybody would find that a controversial stance at all.

Peak television! One could argue that unlike film, television only grows and grows in stature as the more resources and money are thrown its way. Whether you’re part of the small screen migration or still prefer things big and silver, it is hard to deny the impact that has occurred and the major cultural and structural shift that has forced its creators to tap into new and exciting takes on the form and storytelling more generally. I don't think anybody would find that a controversial stance at all.

However, is there a point where this newfound reservoir of creativity and both financial and technical supply is actively harming storytelling? On the fictional side of TV, for instance, I have argued that a series like Westworld is definitely harmed by being offered the benefits of contemporary television's bounty – being given a monumental budget – and the expectations that that breeds from a storytelling point of view to be instantly the biggest and most Capital I Important version of itself without the option of gradually enhancing its characters and narrative through world-building.

On the documentary side, however, the issue is somewhat murkier...

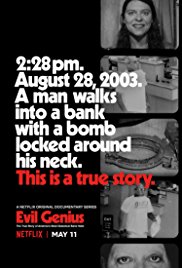

And it’s here that I come to two recent Netflix doc miniseries, Evil Genius: The True Story of America’s Most Diabolical Bank Heist and Wild Wild Country. The streaming giant has taken it upon themselves to become the home of long-form documentary storytelling that are pitched squarely at mainstream audiences in a way that few others can or would even attempt. Their stories of cults and bizarre true crime are the sorts that have had no issue attracting the sort of buzzy online attention that Netflix – or anybody, for that matter – craves, but is the immense creative freedom offered to their employs actually harming the stories these storytellers are telling?

At a total of 191 minutes, Evil Genius doesn’t have enough to sustain itself. Towards its conclusion, the show’s own producer starts appearing off and on screen more and more after having taken on the investigation seemingly for themselves, which only seeks to invoke the memory of The Thin Blue Line, which was able to compose real art out of the darkness of its central crime. Long passages play out over taped voice recordings and video interviews that offer little additional material to the audience’s – or even the participants’ – understanding of the case. Far too long is spent on if not exactly red herrings then at least on diversions that have little pay off while ignoring other elements that feel important.

And by focusing so heavily on Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong, director Barbara Schroeder essentially snookers Evil Genius into a corner. The series gets far too comfortable with itself and her presence despite no willingness to really open up. Far too enamoured by what is clearly perceived to be their ace in the hole or selling this story that didn’t need her (it’s about a seemingly innocent man who had a bomb strapped to him and forced to rob a bank for crying out loud!) Most significantly, and most problematic, is her history of mental health that is often referred to as a means of offering explanation for her actions, yet never fully discussed in any greater context.

Likewise in Wild Wild Country, the production’s remarkable access to Ma Anand Sheela and the figures involved in the cult is an intoxicating lure for directors Maclain Way and Chapman Way. So much so that they spend six episodes worth of drama that I can’t help but feel would have had greater impact in the form of something shorter. Rather than sitting on the edge of my seat, I became comfortable in its story beats and with its rhythmic editing. I found myself going days between episodes because my attention kept slipping.

It’s all well and good for these two miniseries to lay out everything they have over multi-episode arcs, but in doing so they risk inadvertently helping to shine a spotlight on what is left out. How, for instance, could Wild Wild Country go six episodes showing how terrified the townspeople of Antelope, Oregon, were and yet not once think to interrogate the very obvious fact that they were put out of place from the very first instance of the appearance of this woman of Indian heritage and, yes, her brown skin and accented voice. Long before there were guns, they were questioning Sheela’s very essence including the Indian names given to streets and businesses. The fear of the other is an essential part to this story extending to their roots in India and yet never is it brought up because instead we spend too long following otherwise mundane story threads. Oh sure, they all add up to an often fascinating portrait of strange and corrupt forces using the image of peace to hide evil, but what should have been bold, punchy, stunning, ultimate sort of drags to its ending. In its need to show us everything, Wild Wild Country loses its edge.

There is truly much to said for brevity. Consider Barak Goodman’s Oklahoma City or John Ridley’s Let It Fall: 1982-1992, both from 2017, which were able to tell full and compelling stories within relatively subdued runtimes. They were films, not miniseries, of course, but their stories felt no less vital or thorough because of it. They were thrilling for every minute rather than its fits and spurts.

Naturally, as I write this, I am excited for the three brand new instalments to Jean-Xavier de Lestrade’s The Staircase, the 2004 doc epic that feels in spirit like the grand daddy of contemporary true crime storytelling (including the likes of Serial on podcast). I look forward to seeing if the new episodes continue that series’ specialness, which felt unique and overwhelmingly good in the mid-2000s. The passage of time and exhausting attention to detail found in that one works in its episodic structure, much like it did O.J.: Made in America. Unfortunately for Evil Genius and Wild Wild Country, I feel their filmmakers got swept up in the drama and forgot that audiences don’t need everything laid out for us. They instead became almost too clinical in their approach and in spite of their incredible stories lose the wallop they ought to hit.

Release: Both are currently streaming on Netflix

Emmy chances: I suspect Wild Wild Country will be hard to pass up, but the less immediate response to Evil Genius suggests it will have a harder entrance into the documentary or non-fiction series category.