John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

#26 — Kate Gulden, a suburban wife and mother dying of cancer.

JOHN: Here’s one true thing: Carl Franklin’s One True Thing is neither a Lifetime movie, an extended soap opera, nor a “chick-flick.” One True Thing is, in fact, a melodrama centered around a middle-aged woman dying of cancer, embellished with music and openly soliciting your tears. The maternal melodrama, a genre which Streep has revisited frequently, remains near the bottom of the genre totem pole, regularly maligned and dismissed by critics for all their attributes: it is proudly emotional, scored and scripted to produce waterworks, and an undisguised movie, unconcerned with presenting realism through its formal elements. One True Thing, like most contemporary maternal melodramas, is familiar and stylistically plain, and the film is admittedly hampered by a hackneyed framing device, but it also takes seriously issues central to women’s lives, exploring a mother-daughter relationship and issues of long-term marriage, especially the concessions made and female labor expended in keeping a household running smoothly. One True Thing deserves to be taken as seriously as Saving Private Ryan or any other masculine meditation on violence released in 1998. To immediately write off the film, and the genre to which it belongs, is to devalue and belittle the feminine concerns it explores...

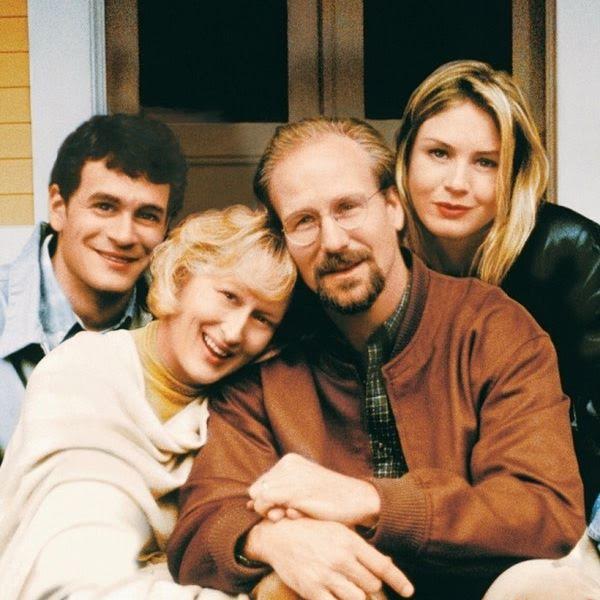

Streep is Kate Gulden, the peppy and slightly domineering mother to Renée Zellweger’s Ellen, a budding New York journalist who immediately discloses to some investigator that she was “never really close” with her mother. We first meet Kate in the present as she prepares for her husband George’s (William Hurt) surprise birthday-costume party, dressed in a blue-checkered dress and red ruby slippers as Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz.

In high spirits and in an even higher pitch, Streep greets her daughter (and her friend, played by Lauren Graham) only seconds before doling out some passive-aggressive remarks. We’re meant to perceive Kate as a frivolous foil to Hurt’s esteemed literary critic, and aside from exchanging some terse glances with Ellen, Streep cosigns this contrast as she hides, dances, and runs around sipping wine during the party, completely relaxed and upbeat. At the end of the night, Streep and Hurt slow dance to Bette Midler’s “Do You Want to Dance” in the living room, a tender romantic interlude, both actors sunny and unguarded, sharing something secretive between themselves in full view of their children. This scene is made more poignant by the fact that Kate is revealed to be battling cancer the very next morning. George asks Ellen to move back home to help take care of her mother, whose condition we are told is rapidly deteriorating. This is your first time viewing One True Thing, correct?

MATTHEW: It is indeed my first time viewing One True Thing, which surprised me, first and foremost, by the fact that it is hardly the Meryl vehicle that her standalone Best Actress nomination had implied. Instead, Zellweger is granted the spotlight and fills it quite capably, whereas Streep is comparably subdued, at least at the outset. Streep is actually first glimpsed, as a remembered projection within one of Ellen’s scattered childhood flashbacks. She’s a picture-perfect ‘60s housewife — coiffed, demure, and silently knitting while riding shotgun next to a pontificating Hurt. When her husband shoots down Ellen’s urgent request to use the bathroom, Kate slightly raises her brows with concern but ultimately says nothing, a gesture that quickly clues us in to the familiar June Cleaver-ish archetype that Streep’s character is meant to fulfill. But Meryl Streep has never been one to rest at playing a mere archetype.

The birthday bash that follows is used to expand upon our initial impression of Kate, lest anyone should think that Streep has gone full Stepford. Throughout the performance but especially in these early scenes, the actress embraces many an opportunity for sheer fun, never more so than when she’s prancing around the party while clad in that adorably ridiculous Dorothy get-up or, later, wailing along to Bette Midler’s “Friends” with an equally off-key gal pal, much to Ellen’s chagrin. But Streep is also masterful enough to balance this merriment with honesty and thus layers these moments with emotional insight, evidenced in the way she keeps eagerly clocking Hurt with quivering, wide-eyed expectation during his party, hoping to secure her husband’s approval of a gathering that is surely more up her own alley than his.

Kate may be an apologetic and largely outward-facing personality, one prone to masking even her deepest annoyances behind a perky, giggling facade, but she is neither a frivolous woman nor a force of nature. She’s far more in line with the decorous, unpretentious, and sometimes plain Everywoman persona that the ever-exceptionalized Streep has essayed infrequently over the course of her career in some of her most overlooked projects, like Falling in Love and Hope Springs.

Streep, accordingly, ingests her every shot in the beginning of One True Thing with the breath of ordinary life; when this breath is inevitably deprived, it rightfully feels like a tragedy. She doesn’t try to distinguish Kate beyond the confines of the character as-written, but embodies all that is true and habitual about her, so that a scene in which Kate expresses subtle disapproval towards Ellen while performing a domestic duty is as much about the chore being performed as it is about the frank opinion being subliminally shared. But Streep also doesn’t diminish Kate’s occasional tendency to suffocate, as in a later scene when she continually interrupts one of Ellen’s work calls to confirm if she’ll be accompanying her to a Halloween fair happening that same day. In exchanges like these, the character could have easily registered as another Meddling Mom caricature, but she doesn’t because Streep’s voice, so often kept in her lower register, and her demeanor are grounded in reality and the needs and feelings of a given moment.

Streep, accordingly, ingests her every shot in the beginning of One True Thing with the breath of ordinary life; when this breath is inevitably deprived, it rightfully feels like a tragedy. She doesn’t try to distinguish Kate beyond the confines of the character as-written, but embodies all that is true and habitual about her, so that a scene in which Kate expresses subtle disapproval towards Ellen while performing a domestic duty is as much about the chore being performed as it is about the frank opinion being subliminally shared. But Streep also doesn’t diminish Kate’s occasional tendency to suffocate, as in a later scene when she continually interrupts one of Ellen’s work calls to confirm if she’ll be accompanying her to a Halloween fair happening that same day. In exchanges like these, the character could have easily registered as another Meddling Mom caricature, but she doesn’t because Streep’s voice, so often kept in her lower register, and her demeanor are grounded in reality and the needs and feelings of a given moment.

My favorite line reading in the entire performance comes when Kate first realizes that Ellen intends to take a leave of absence from her high-pressure job at New York magazine and care for her mother full-time. Kate voices many objections to this decision, but the one that stings the hardest is the one Streep very nearly suppresses, whispering it beneath her breath: “Man, you’ll hate me.” These are the words of a mother who has long feared this exact possibility and is in no way blind to her daughter’s discomfort in the face of her own middle-class conventionality. Streep’s self-effacing sheepishness makes this worry painfully palpable, while also confirming that the actress will indeed be seizing each and every chance during this movie to utterly break our hearts. What else stands out for you about Streep’s second (and far superior) Kate of 1998?

JOHN: If One True Thing is ever discussed in the context of Streep’s career, aside from the fact that it allowed her to surpass Bette Davis’ 10-nomination record, it is probably to sing hosannas at Kate’s late-film confrontation. At this point, Ellen’s estimation of her father has plummeted. After piecing together dad’s infidelities, slight alcoholism, and feigned literary prowess while he neglects his wife during her dying days, Ellen receives a by-now-habitual “working late” call from him. Streep, sitting on her bedroom floor, rummaging through old photographs and letters, looks frail and glum as she prepares to say her goodbyes. She clocks the resentment in Ellen’s voice and, just as we’re expecting Kate to sheepishly, and perhaps naïvely, wither away as the unsuspecting fool, she instead challenges her daughter with a forceful self-awareness that complicates our understanding of this seemingly guileless housewife. “I want to talk to you. Sit there,” Streep demands. “Now you listen to me because I’m only going to say this once, and I probably shouldn't say it at all. There is nothing that you know about your father that I don’t know — nothing — and understand better.” She admits all of this, to our astonishment, with the assured, piercing sincerity that makes you sit up straight in your seat, jaw agape, eyes welling with tears.

Streep certainly plays the long game in exposing this emboldened facet of Kate’s personality, elucidating the allowances made throughout a marriage as thoughts that have long crossed her mind but have never before left her lips. “No, he’s not the person you thought he was,” she says, speaking not about Ellen, but herself. “But he’s your life. And the kids and the house and everything that you do is built around him. And that’s your life. That’s your history too.” Perhaps these sentiments are arguably out of step with the feminist creations that are arrayed throughout Streep’s filmography, but it’s exciting to watch Streep defend Kate’s selfless nature. “I want to talk before I die,” she says, rasping her voice, holding up a pale finger to Zellweger. Even more astonishing is Kate following up these truth-bombs by confessing that she hasn’t got much else to say, just after demanding that Ellen listen to her speak. “I’m... sad,” she confesses, darting her eyes, adjusting her back. “I’m sad that I won’t be able to plan your wedding,” she admits. Her sadness is walloping, the full effect of her disease made palpable by Streep’s nuanced realizations of her impending absence.

This is the moment that One True Thing has been leading up to, the emotional crescendo that matches Streep’s abilities and elevates the entire performance, as Kate finally urges her daughter to choose happiness: “It's so much easier to choose to love the things that you have, and you have so much, instead of always yearning for what you're missing, or what it is you're imagining you're missing. It's so much more peaceful.” Streep speaks these truths as if they had never been uttered by anyone else before, a twinkle of sadness in her eyes betraying the encouraging dialogue. It’s a devastating and poignant moment that deserves to speak on its own, so I’ll leave it as Kate does, by admitting that I’ve not much else to say. Have I liquefied you? Is there more that you’ll remember about One True Thing beside this one truly great scene?

This is the moment that One True Thing has been leading up to, the emotional crescendo that matches Streep’s abilities and elevates the entire performance, as Kate finally urges her daughter to choose happiness: “It's so much easier to choose to love the things that you have, and you have so much, instead of always yearning for what you're missing, or what it is you're imagining you're missing. It's so much more peaceful.” Streep speaks these truths as if they had never been uttered by anyone else before, a twinkle of sadness in her eyes betraying the encouraging dialogue. It’s a devastating and poignant moment that deserves to speak on its own, so I’ll leave it as Kate does, by admitting that I’ve not much else to say. Have I liquefied you? Is there more that you’ll remember about One True Thing beside this one truly great scene?

MATTHEW: I think Streep deserves added praise for never appearing to reclaim the movie away from Zellweger, who fuels the film with her righteous irritation over Hurt’s behavior and even manages to make the most of that awkward framing device, which keeps pushing these events into the form of a postmortem procedural. Streep, meanwhile, slyly bolsters her costar’s performance by giving her so many different and often unanticipated emotional cues to play off of, carefully choosing which interactions to press her daughter and which to retreat, which moments to let her guard down and which to simply let things be, in turn varying Zellweger’s work.

And if Kate Gulden appears at odds with some of the feminist characters that have predominated Streep’s career then that’s only because the moviemaking culture at-large prefers to champion feminist viewpoints when depicting the superheroic and the extraordinary, often at the critical expense of ordinary women, whose experiences deserve the same cinematic space and recognition. For me, Streep’s performance, first and foremost, defends the honor of a figure familiar to many an audience member, myself included, but who remains so frequently misunderstood in the movies: the maternal homemaker. Streep keeps delicately challenging our assumptions about the type of woman Kate is, without boiling her down into a thesis statement about the suburban wife-mother or heroizing the character’s traits into those of a domestic goddess. She opts for complexity and candor, never belaboring her character’s decline so that what emerges is a tough-minded portrait of both deathbed illness and female domesticity.

The scene you detailed above — in which Kate corrects her daughter, in no uncertain terms, that there is no one who knows her family better than her — is definitely the crown jewel of the performance; the directness of Streep’s playing in this insistently honest confessional startles like an icy gust of air to the face. But there are several scenes that compel almost nearly as much, from Kate’s penetrating kitchen explosion over being confined to a wheelchair to her refusal to engage or even look at her children at a tree-lighting ceremony as they each realize that this will likely be their last Christmas with mom.

As Kate’s illness progresses, Streep shows us Kate trying to retain her chipper aura, gradually uncovering the cracks in the character’s grinning mask so that a tired sigh or nervously-directed glance speaks volumes about the strain of keeping such a mask intact. The performance accrues in intensity and matter-of-factness during Kate’s later flashes of anger; these moments feel like a natural progression of character rather than a break in behavior, although Streep could have probably showed some earlier flashes of this sterner streak. Then again, just when it seems that Streep may be pushing too hard or even rushing too quickly to emotional conclusions, her approach ebbs and relaxes as the thought of death (and, with it, an end to suffering) actually seems to put Kate at ease. It is almost unspeakably devastating to watch such an engaged and electric performer devoid of her spirit, leaving us, in her final scenes, with only the shell of a woman. Streep’s work in One True Thing is seldom held up among her most outwardly virtuosic tours de force. But when taken on its own discreetly lived-in merits, her performance helps us understand that love and familial devotion, even at their most total and tender, never come without daily sacrifices. By illuminating this, Streep carries us to a realm of everyday experience, with all its heartbreaks and ambivalences, that few screen actors — and few screen narratives — ever really visit, much less explore.