Daniel Walber's series on Production Design. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

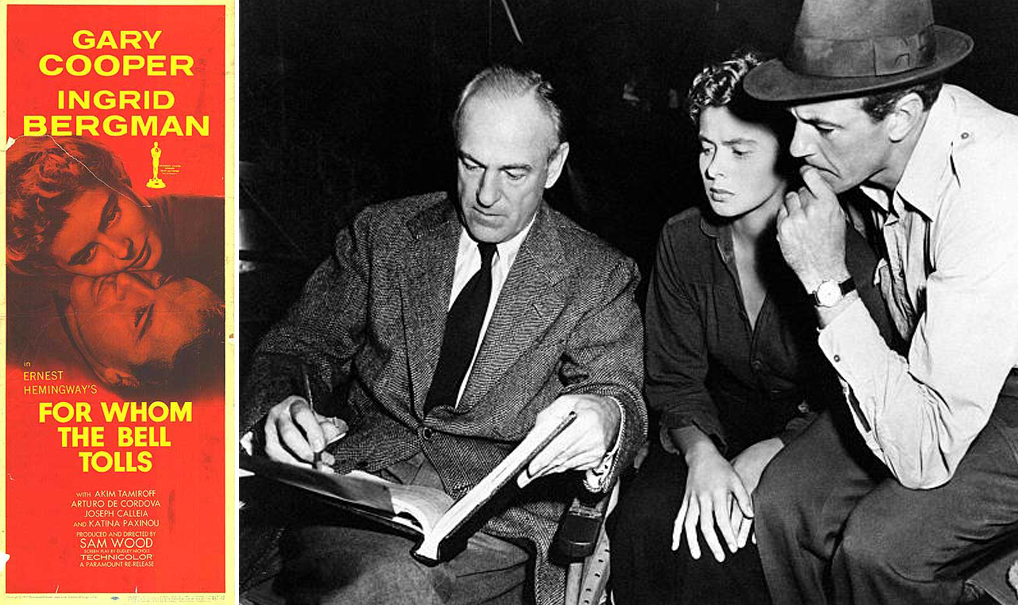

Sam Wood directing Ingrid Bergman and Gary Cooper in 1943's top picture

Sam Wood directing Ingrid Bergman and Gary Cooper in 1943's top picture

It can seem kind of crazy that For Whom the Bell Tolls was the top box office hit of 1943. The star power of Ingrid Bergman and Gary Cooper played into it, of course. So did the fact that it was an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s popular and recent novel. And there’s the obvious appeal of Cooper fighting a bunch of Fascists, a year and a half after America’s entry into World War Two.

The thing is, he doesn’t actually do all that much fighting. No one in the film does. It’s mostly a contemplative interlude on the fringes of the Spanish Civil War, a brutal vacation with a band of hardened guerrillas, a doomed love story built from trauma and consummated on the high rocks. It’s 165 minutes of memory, frustration and stasis.

It also wound up with nine Oscar nominations, including both cinematography and art direction. And the collaboration between cinematographer Ray Rennahan and the design team of Hans Dreier, Haldane Douglas and Bertram C. Granger is really the highlight of the film, even against the life-giving energy of Katina Paxinou’s Oscar-winning performance...

Daytime in this film is largely built upon the majesty of the Sierra Nevada mountains, specifically those of Stanislaus National Forest. But night is largely a studio affair, the thin mountain air pumped into a Los Angeles sound stage. The rocky sets are backed up by simple matte paintings that only sparingly gild the sky with stars and the tops of distant mountains. Here’s a typical example.

Here is a loneliness and isolation quite literally protected from the outside world by the flat, deep blue sky of these matte paintings. There is a real sense of physical limitation throughout, despite how much everyone talks about the surrounding movements of both Republican and Nationalist troops. Even the handful of Fascist soldiers who occasionally wander by seem more like ghosts than people.

This picturesque retreat is ideal for the kind of slow, psychological communion that is shared by Robert (Cooper) and Maria (Bergman), and to some extent Pilar (Paxinou). The two women narrate their traumas from the early days of the war as if describing recurring dreams. Pilar’s description of the early violence in her town is recreated by the film, a nightmare in a much lighter color palette.

Maria’s trauma, meanwhile, is deemed too terrible for reenactment. Instead, we see it in Bergman’s face. Her performance, characteristically passionate despite the weaknesses of her material, is quietly underlined by the shadows on the rocks and the deep blues of the matte sky. Here, far from everything, is a space for the slow reconstruction of one’s own self.

Eventually the outside world does make its presence known. Robert sends one of the guerrillas to warn the Republican front lines of the impending Nationalist advance. When the man arrives, however, we see no army. The Republican camp is made up of little more than light and shadow, a fence and the threat of dawn rising on a simple studio backdrop.

This doesn’t seem to be some tangential point about the size and strength of the Republican forces. Rather, it’s as if the film cannot allow space to a living, breathing army without breaking the calm, blue nocturne that has enveloped the characters up to this point. Instead, the Republican camp is presented like a shadow puppet theater, only a hint of the real world before the Nationalist tanks really do arrive.

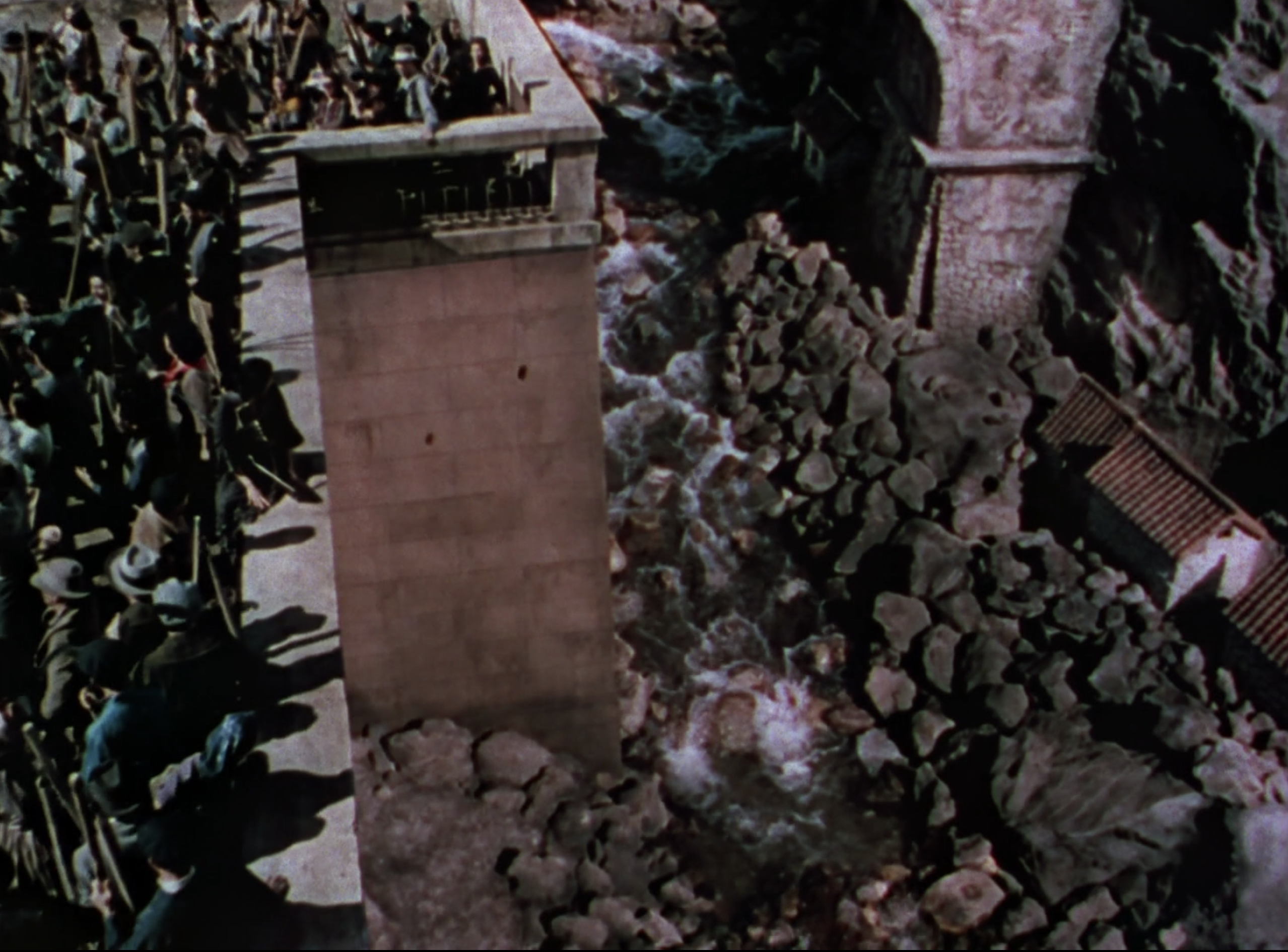

After all, this strange respite cannot last forever. The Nationalist tanks finally barrel in, the shining matte-moons come down and Robert is forced to complete his mission to demolish the all-too-tangible (if still not quite real) bridge. This bridge is the only hard fact of the film, in a sense, standing in for the equally blunt reality of death. Once it finally comes down, Donne’s titular bell will toll for Robert himself, and the contemplative isolation of the previous two hours will feel like an implausible island of dream.