By Glenn Dunks

We’re playing a bit of catch up this week in the lead up to the hectic fall festival and award season. Nathaniel already looked at a bunch of recent indies and mainstream blockbusters. Now it’s my time to look at a trio of recent documentaries all about musicians: Whitney, The King, and Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda.

Why can’t we get a documentary about the one and only Whitney Houston that truly works? Kevin Macdonald’s Whitney follows on a year after Nick Broomfield and Rudi Dolezal’s Whitney: Can I Be Me, an appalling film that Whitney easily supplants if only by default. Macdonald, an Academy Award-winner for One Day in September (a personal favourite, but he is probably best known as the director of The Last King of Scotland) brings a glossy sheen to Whitney that was missing in that earlier title, but it still falls short of giving Houston the treatment she deserves.

The problem lies in these filmmakers choosing the focus on the tragedy of Houston’s downfall over the transcendence of her meteoric rise to fame and her exceptional, unparalleled talent. Her death is an important part of her narrative, of course, but it cannot be ignored that two white male directors – a Brit and a Scot at that – have chosen to mirror the success of Amy and focus on her devastating end to drugs and disease and make her music secondary. Little effort is made to examine her music and its impact beyond a stretch discussing her famous interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner”. Houston’s influence on other black musicians is ignored, as are large swathes of her career that figure heavily in her story. Not at all by accident surely because it disrupts the tragic narrative, but the fact that her final album was a huge success is glossed over, too.

Worst of all, Macdonald uses the revelation that Whitney was sexually abused by a relative as not just a sick third act twist, but also suggesting it was the reason for her homosexual relationships (particularly of that with Robyn Crawford who has been wisely absent from both films). Whitney can’t escape the shadow of the Houston family, and while I appreciate that their approval was essential to allow Macdonald access to Whitney’s catalogue as well as interview access to living members of her family, Macdonald seems helpless at stopping them from shaping the film to their whims. Bobby Brown is let off the hook with a simple shrug, while Whitney’s mother, Cissy Houston, withholds far more than she reveals. As it stands, Whitney is technically efficient – Sam Rice-Edwards’ editing and the film’s sound team earn MVP honours – but frustrating

If Macdonald focuses squarely on his titular subject, then The King director Eugene Jarecki takes Elvis Presley and uses him to explore America more broadly as an empire in declide. Revolving around a cross-country drive in Elvis’ 1963 Rolls Royce, Jarecki assembles a collection of musicians and famous faces (Alec Baldwin, Emmylou Harris and Ethan Hawke, also a consulting producer, among them) and uses Elvis as the backdrop for an entertaining if disheartening state of the union address of sorts.

If Macdonald focuses squarely on his titular subject, then The King director Eugene Jarecki takes Elvis Presley and uses him to explore America more broadly as an empire in declide. Revolving around a cross-country drive in Elvis’ 1963 Rolls Royce, Jarecki assembles a collection of musicians and famous faces (Alec Baldwin, Emmylou Harris and Ethan Hawke, also a consulting producer, among them) and uses Elvis as the backdrop for an entertaining if disheartening state of the union address of sorts.

Far more up my alley than a typical birth to death biography, I found The King wildly entertaining and a more interesting take on its subject than the standard documentary you’re likely to find on him. Unexpectedly for a film about such a revered figure as Elvis, Jarecki has included Presley critics like Van Jones and Chuck D of Public Enemy. Jarecki then attempts something ambitious and uses Elvis as the pivot point for America becoming the capitalist society that it is today with the film positing that the rabid obsession that he bred in fans lead to a society that craved unrealistic wealth – American was, after all, a country built to not be reigned by a king – with equally unrealistic ideas of what the “American dream” was and who could achieve it, further entrenching racial divides, and the worshipping of things not worthy of worship. As a narrative choice, it’s a remarkably brave one.

It’s that unpredictability that allows its rather scattered approach to not become a hindrance to The King’s storytelling. Using film clips and bolstered by a soundtrack of not just Elvis standards, but musical curve balls from Sigur Ros, Billie Holiday, Lana Del Rey and ABBA by way of rap outfit Immortal Technique, this is a surprisingly visual film, too. Cinematographers Tom Bergmann, Christopher Frierson and Étienne Sauret do more than one might expect with a documentary set predominantly within and around a single automobile and make great use of juxtaposing the harsh realities America’s so called heartland with the neon-lit cityscapes that better represent the modern America.

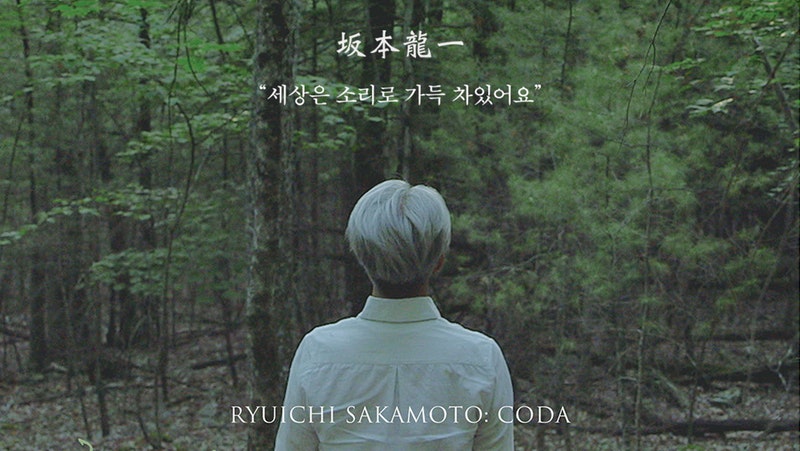

After those two, it’s all the better that Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda is a soothing tonic of a documentary. Tellingly, Stephen Nomura Schible’s film is the only film of the three with its subject still alive. Nonetheless, it has a melancholy quality to it that feels directly lifted from one of Sakamoto’s beautiful, haunting, intricate piano compositions that soundtrack this film. Far less interested in telling the life story of this Oscar-winning musician and more about attempting to replicate his essence in the form of a documentary, Coda begins with Sakamoto searching through radioactive tsunami-affected Fukushima to find a piano that got swept away and yet still plays music and evolves into Sakamoto reflecting on his own existence as he is treated for cancer and works on the score for The Revenant.

Coda is such a richly rewarding experience, and one that moves so gracefully to its own intimate rhythms like fluttering notes on a page, that I wish there wasn’t a stretch in the middle where it becomes a more traditional history lesson. Oh sure, it’s interesting to hear the man discuss The Last Emperor, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, The Sheltering Sky and more, but for a film that rarely comes across as conventional – even the subject himself is not somebody we expect to receive such a gorgeous documentary treatment – it was the only part that felt like it had to lead viewers as opposed to allowing them to let Sakamoto and the film wash over them. Otherwise it is a strong and charming glimpse into his life.

Oscar Chances: I suspect Coda has the strongest chance of the three, but after several years where music docs were very popular with voters, perhaps that phase is over. Still, Macdonald and Jarecki have pedigree and that cannot be discounted should the branch be in the mood.