Team Experience will be celebrating one of the world's most acclaimed auteurs for the next week for the 100th anniversary of Ingmar Bergman's birth. Here's Sean Donovan...

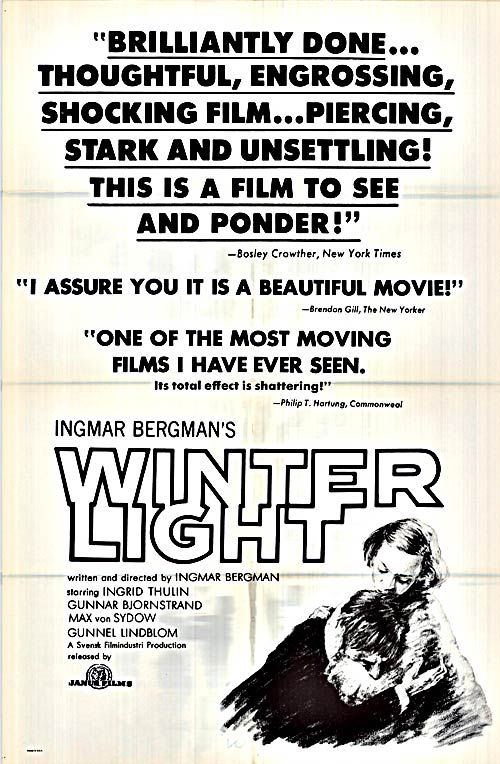

Perhaps none of Ingmar Bergman’s films do more to conjure clichés of what a ‘Bergman film’ is than 1963’s Winter Light. While Persona is undoubtedly the cinephile consensus choice for his best film, and The Seventh Seal or Wild Strawberries are his most widely-seen, frequently adorning college syllabi about the history of European cinema, the morose sadness for which his work became known feels most exemplarily expressed in Winter Light. The second part of a trilogy about “the silence of God” (starting out grim already), Winter Light’s infinite quiet, stark black-and-white cinematography, freezing cold exteriors, and tear-soaked monologues scream BERGMAN in capital letters. It’s strange viewing with which to start a hot summer weekday morning, but here we are. Though the severity of film that threatens to overwhelm you, it is my personal favorite of the Bergman canon, superbly acted and filmed with a brisk lightness that befits an auteur frequently in danger of getting weighed down in heavy-handedness. A freezing shot of aquavit on the rocks can knock you over and have you questioning the purpose of your life.

Winter Light may be reaching new audiences this year as it has received a renewed relevancy from Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, an unofficial remake blatantly taking the premise and applying it to the contemporary United States...

Winter Light follows a nearly real-time dissection of the lives of Thomas Ericsson (Gunnar Björnstrand, brilliant), the pastor of a small rural Swedish church, and the atheist schoolteacher Märta Lundberg (Ingrid Thulin) who loves him. Recruited by a pregnant woman (Gunnel Lindblom) to counsel her anxious husband Jonas (Max von Sydow), Thomas can barely get out of his haze of depressed hopelessness to address Jonas’s fears of nuclear apocalypse. When Jonas is later found dead of suicide, Thomas begins to spiral, acting out aggressively at Märta who, in her own tragic arc, can’t stop re-calibrating her own hurt feelings into a twisted form of captive compassion. Though Thomas is the preacher and Märta the educated atheist, Märta’s own moral code makes her thoroughly the more ‘devout’ of the two.

Winter Light follows a nearly real-time dissection of the lives of Thomas Ericsson (Gunnar Björnstrand, brilliant), the pastor of a small rural Swedish church, and the atheist schoolteacher Märta Lundberg (Ingrid Thulin) who loves him. Recruited by a pregnant woman (Gunnel Lindblom) to counsel her anxious husband Jonas (Max von Sydow), Thomas can barely get out of his haze of depressed hopelessness to address Jonas’s fears of nuclear apocalypse. When Jonas is later found dead of suicide, Thomas begins to spiral, acting out aggressively at Märta who, in her own tragic arc, can’t stop re-calibrating her own hurt feelings into a twisted form of captive compassion. Though Thomas is the preacher and Märta the educated atheist, Märta’s own moral code makes her thoroughly the more ‘devout’ of the two.

An incredibly economical film at 81 minutes, Bergman’s master status feels earned by the sheer purposefulness of each and every scene, making a film where not a lot “happens” in the Hollywood sense of the term feel compact and pressurized. Like the ethereal English title Winter Light, there is a sad ambiance to the film that filters elegantly through each and every scene, carrying a significant emotional wallop. The ‘light’ itself is superbly captured by Bergman’s legendary cinematography Sven Nykvist, with the marvelous ability to capture minuscule changes of light shifting through church windows.

In 2018, Paul Schrader felt the need to up the ante; the conclusion of First Reformed is far more, shall we say, explosive than anything that happens in Winter Light.

Winter Light (1963)

Winter Light (1963) First Reformed (2018)

First Reformed (2018)

First Reformed is, in a way, a far more cynical film. Schrader sneers at the church’s touristy gift shop as some corporate bastardization of faith when such economic considerations feel far removed from the intimate desolation of Bergman’s film. Schrader's film also makes the curious choice of swapping the size of the female roles. Lindblom’s pregnant Karin barely registers in Winter Light, whereas her contemporary American alter ego, Amanda Seyfried’s Mary, almost steals First Reformed as a complex woman with her own relationship to her Christian faith.

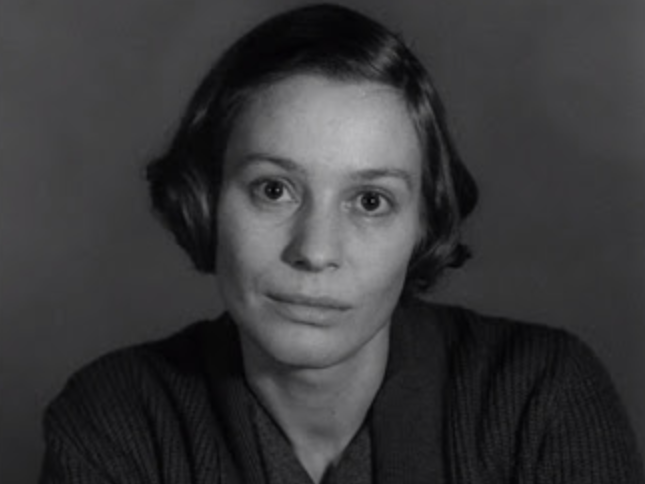

Even with this particular upgrade, the reduction of Märta’s role had me feeling betrayed by First Reformed. One of the most pulverizing sequences of Winter Light is a nine-minute shot of Märta as she recites a letter written to Thomas about her resilient love for him, a captivating monologue that never indulges in melodrama but holds the viewer sutured to quiet changes in facial expression by the masterful Ingrid Thulin. Never receiving the international celebrity of Liv Ullmann, Ingrid Thulin’s fame stayed within Europe perhaps due to her role as a chameleon for Bergman, with roles as diverse as the ‘good wife’ with Grace Kelly-esque fashion polish in Wild Strawberries, a femme fatale in Hour of the Wolf, and a frenzied grand guignol diva in Cries and Whispers. The dowdy, sad, quietly ardent Märta lacks the grand-standing of those other characters but is Thulin’s masterwork, bringing a melancholy self-awareness to a character rooted in self-destruction.

Ingrid Thulin as "Marta"

Ingrid Thulin as "Marta"

In First Reformed, Märta is reduced to a secondary character, Victoria Hill’s choir director Esther, sporting a tight ponytail that makes a compelling visual analog for Thulin’s knit cap. Through no failure of her own, for Hill works with what she can, the film’s concerns always feel elsewhere in her few scenes. The reduction of this role has a monumental effect on the underlying premise. Winter Light forces the viewer to sit with the verbal cruelty Thomas inflicts upon Märta, because Märta is a co-lead, and her processing of a sharp exchange between the two lingers over the remainder of the film. When the same basic conversation appears re-contextualized in First Reformed, Ethan Hawke’s Rev. Toller breathing fire about how Esther repulses him, it is a quick passing scene that refuses to linger on Esther’s response. This different weighting of female characters in the new film ends up privileging male existential ennui over female rejection and pain. Winter Light’s insistence on showing the selfish, cruel side of its depressed priest is perhaps evidence of a braver film, more willing to set up barriers to viewers’s neat and easy identification with a character.

In the final moments of Winter Light, Märta sitting alone in the last pew of the church lets out a quiet, desperate prayer: “If only we could feel safe and dare show each other tenderness.” The sad, and almost humble sincerity of the prayer is emblematic of Winter Light as a whole, an elegant song of sorrow, with the slightest hope for something better peeking out from under the snow.