TIFF kicks off today!! In addition to our regular coverage, Chris Feil will be covering a sampling of the festival's LGBTQ global cinema...

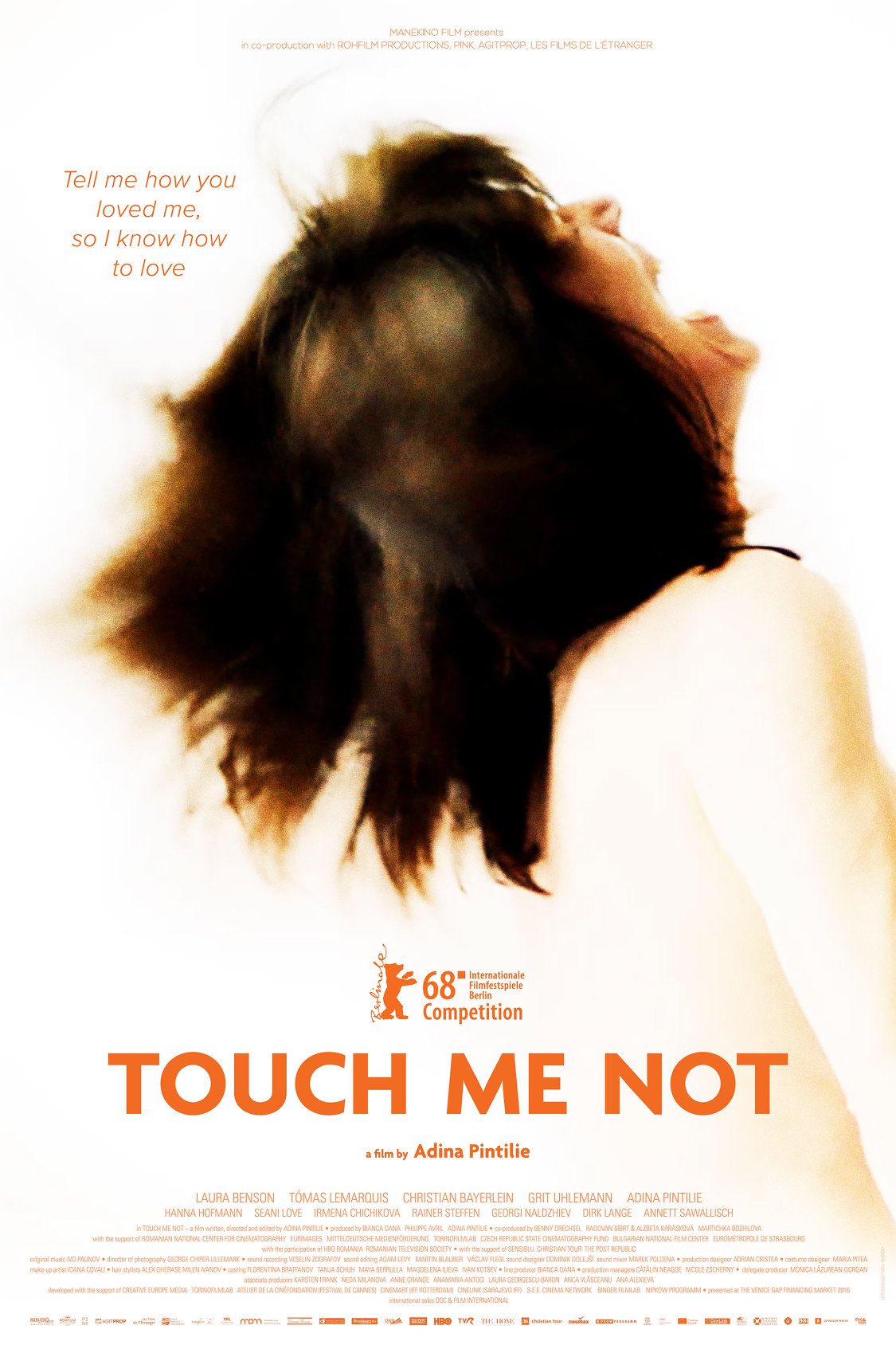

Adina Pintilie’s Golden Bear-winning piece of experimentation and sexual reflection Touch Me Not opens on a landscape of the naked male body, anonymous and alien, shot with a deliberate distance that doesn’t deceive the film’s tension between curiosity, impulse, and terror. While this quickly establishes the psyche of Pintilie’s piece, it is about to become far more personal, with its players all playing themselves or versions thereof. Its fourth wall is never broken because it was never built in the first place.

Adina Pintilie’s Golden Bear-winning piece of experimentation and sexual reflection Touch Me Not opens on a landscape of the naked male body, anonymous and alien, shot with a deliberate distance that doesn’t deceive the film’s tension between curiosity, impulse, and terror. While this quickly establishes the psyche of Pintilie’s piece, it is about to become far more personal, with its players all playing themselves or versions thereof. Its fourth wall is never broken because it was never built in the first place.

The film centers largely on two emotionally stunted characters (or “characters”), struggling to experience both physical and emotional connection...

Laura is outright revulsed, comfortable with bodies only at a distance as an internal fury overtakes her. Tómas participates in a new age-ian group therapy session with disabled persons at a hospital, his frozen silence in direct contrast to his group partner Christian. Between Laura’s lurkings over Tómas in the hospital, the film becomes a series of vignettes of the two breaking down their traumatic barriers.

Pintilie molds Touch Me Not with a painful intimacy that dares you to look away from its frankness, and somewhat embraces the potential limitations just as it embraces the psychic abyss. The film is primarily defined by its conviction, the certainty that its methods of meandering soul-bearing will find the source of suffering even if it means the occasional pitfall. When the film nails it, like Laura’s sequences with a holistic BDSM sex worker/therapist, it’s gasp-inducingly alive. When it doesn’t, Touch Me Not simply sloshes about, like in a third act sex club set piece that brings together most of its secondary characters with inexact purpose.

And it shouldn’t be confused as sex-negative, for it is quite affirming of the sexual variety of its supporting players. While the film dabbles in unspoken homoeroticism between Tómas and Christian, Laura approaches queerness more openly when she seeks out the assistance Hanna, a trans sex worker. Hanna is the most fully formed character of Touch Me Not’s quasi-therapists to Laura, confident and open about her desires, her life, and her identity. Everything that Laura and Tómas are not.

Though we become Laura as the film adopts her voyeurism as it lurks through the hospital and provides not-so-casual visions of fetishism, Pintilie’s delivers a perspective that is neither judgmental nor passive. The director hovers over the film in Orwellian fashion until she swaps positions with Laura for a spell, allowing its metafiction to recontextualize and perhaps diffuse any notions the audience might have that she’s been exploitive. By revealing her our physicalized anxiety, Pintilie cements the film as a curious one in the dire sense. All this soul-baring isn’t as exploitive as we fear (particularly when presenting disabled bodies), it’s meant to empower and verbalize the repressed or inexpressible. But it never soothes either. The nerve it tries to alleviate is simply too raw for such pretense.

Laura (and the director as well, as intimated through confessional) is terrified of her rage. But the film handles the tempest inside with a affectionately unflinching grasp, resulting in bracing moments where we forget its artifice and the degree to which some of what we are seeing might be put on. It’s a surprising film in that it’s examining internalized anger while not itself being necessarily angry. Or maybe it doesn’t want to be pinned down so easily, or its tangle of moods to be reduced to overly simple descriptors. Touch Me Not’s attempt to be all things at once doesn’t work nearly all of the time, but when it does, it blindsides.

The film’s meditativeness is sometimes a mask it can hide behind, particularly when its fiction becomes far more labored than its reality. Tómas and Christian’s relationship feels the most shepherded, as if it was meant to provide a backbone of a plot that the film forgets it doesn’t quite need. Tómas also has a former love he hounds, a detail that confuses and never incorporates organically. The film’s flaws are easily spotted, but also beside the point.

In discussion with Laura, Pintilie (or perhaps a version of her, considering the lines between fiction and reality are meant to be indistinguishable here) describes the film as coming from something “not in the words area.” “Before words,” Laura responds. Touch Me Not is reaching for that kind of primacy, one it doesn’t always need to define with clarity.

Grade: B-