Please welcome new contributor Abe Fried-Tanzer

Two years ago, despite over a dozen submissions since 1978, Lebanon hadn’t had a film nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Now, the small Middle Eastern country is looking at a likely second consecutive nomination. The Insult was a powerful portrait of two adult men divided by hate and behaving like children. Capernaum, equally compelling, spotlights the opposite: a child acting like an adult, seemingly far more capable of understanding the world for what it is than the actual grown-ups in his life.

Two years ago, despite over a dozen submissions since 1978, Lebanon hadn’t had a film nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Now, the small Middle Eastern country is looking at a likely second consecutive nomination. The Insult was a powerful portrait of two adult men divided by hate and behaving like children. Capernaum, equally compelling, spotlights the opposite: a child acting like an adult, seemingly far more capable of understanding the world for what it is than the actual grown-ups in his life.

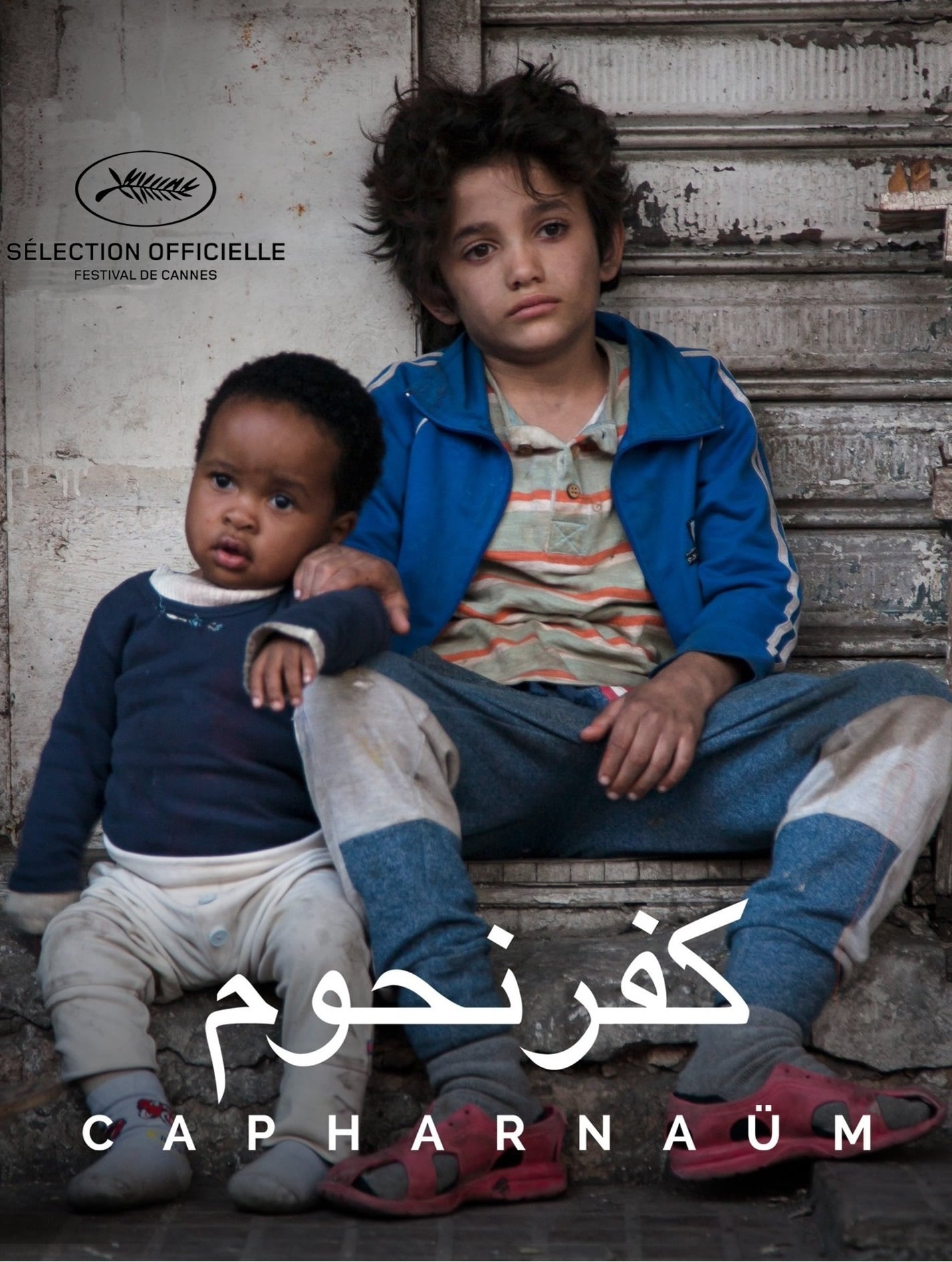

The sensational description of this film’s plot focuses on its approximately twelve-year-old protagonist Zain (Zain Al Rafeea) suing his parents for giving birth to him. That summary may conjure up courtroom drama, but that’s far from the truth of the film which takes place on merciless streets. Instead, Capernaum provides a layered look at what it means to be responsible for another person...

Zain grows up in an extremely crowded household where he spends his days working at a corner store. He sees the way that the store’s owner and his family’s landlord looks at his younger sister Sahar (Cedra Izam), and instinctively knows that it is wrong. His parents’ decision to sell Sahar to the older man to create what they believe will be some financial stability for her pushes Zain over the edge, prompting him to run away from home.

Once out on the streets, Zain comes across another questionable instance of parenting. Rahil (Yordanos Shiferaw) is an undocumented Ethiopian immigrant who brings her infant son Yonas (Boluwatife Treasure Bankole) to work and hides him in her belongings to assure that they won’t be separated. Zain soon becomes the child’s babysitter, allowing her to earn a living while her son remains safe at home, but like Zain’s own family living situation, this too is doomed to fail.

The Insult examined the politics of Palestinians living in Lebanon and being looked down on by native residents. This film tackles a more diverse population, with Syrian and Ethiopian refugees who have escaped their own countries but live in daily fear of being caught or having their families torn from them. This explicit portrayal of a fragmented society is all the more effective because it identifies its characters’ origins but never dwells, immediately moving to survival mode. How do Zain and Rahil exist on a daily basis? What can they do to get by in their new reality?

The greatest boon to this third feature film from acclaimed director Nadine Labaki is the naturalistic performances that give this film an authenticity and authority. Using non-professional actors is always a gamble, but Labaki expertly guides them, placing them in roles not all that different from their real lives and working the script around their organic responses to the situations presented. This film feels so real because the actors don’t ever seem to be acting, playing out scenes that might as well have happened to them. As Zain, Al Rafeea is particularly poignant, conveying an incredible maturity that is sometimes quickly replaced by childlike exhaustion that most might expect him to display permanently.

Nadine Labaki directing her leading man

Nadine Labaki directing her leading man

After a Grand Jury Prize at Cannes and a Golden Globe nomination, Capernaum made the nine-wide shortlist for the Oscar category, and will hopefully be included when nominations are announced in just a few weeks. It’s exactly the type of international cinema that should be honored, addressing its own cultural and societal issues in a universal and relatable way. B+