By Lynn Lee

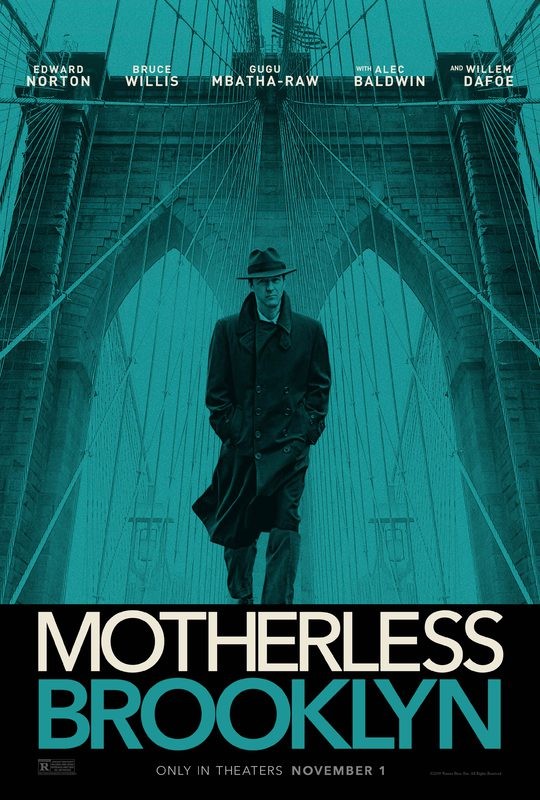

Is Motherless Brooklyn just another high-profile Oscar hopeful turned dud-on-arrival? The early signs for Ed Norton’s long-gestating passion project have not been encouraging, to put it mildly. Reviews on both the festival circuit and the film’s general release and here at TFE have been tepid, the box office even more so. Its awards prospects are pretty much nil. It’s also not the kind of movie that’s likely to find success through word of mouth or build a long-term cult following, and its chances of future critical reevaluation are uncertain at best.

Is Motherless Brooklyn just another high-profile Oscar hopeful turned dud-on-arrival? The early signs for Ed Norton’s long-gestating passion project have not been encouraging, to put it mildly. Reviews on both the festival circuit and the film’s general release and here at TFE have been tepid, the box office even more so. Its awards prospects are pretty much nil. It’s also not the kind of movie that’s likely to find success through word of mouth or build a long-term cult following, and its chances of future critical reevaluation are uncertain at best.

All of which makes me a little sad, because I quite enjoyed the film, and think Norton deserves more credit than he’s getting for what he’s accomplished...

Motherless Brooklyn is a throwback in the best way, a thoughtful, unabashedly square and earnest (but not preachy) social conscience movie masquerading as a twisty noir mystery – or maybe it’s the other way around. It’s beautiful to look at and listen to, capturing a retro, Edward Hopper-esque New York that probably never really existed yet succeeds as a melancholy-tinged love letter to the city, as well as a dreamy hat tip to Harlem jazz. It also features one of my favorite performances from Norton in years (more on that in a minute).

The movie’s been dinged for being too long, too slow, and too convoluted, but while it does run nearly two and a half hours, it's well paced and thoroughly engrossing -- I never once felt restless or distracted, even its quieter moments. At the same time, I didn’t have any trouble following the turns of the plot, which involves Norton’s sad-eyed Tourette’s-afflicted private eye, Lionel Essrog, attempting to solve his mentor’s murder and getting drawn into a Chinatown-esque puzzle of municipal corruption and carefully buried family skeletons.

In an unusual move, Norton transplants the Jonathan Lethem crime novel on which the film's based – which was written and set in the 1990s – to the 1950s and inserts a fictionalized version of New York City planner Robert Moses (played here by Alec Baldwin) as the chief villain. The script is effectively a mashup of Motherless Brooklyn (the novel) and The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s 1974 biography-as-evisceration of Moses. While I haven’t read either book, I was impressed by how smoothly Norton was able to meld the two.

Michael K Williams as "Trumpet Man"

Michael K Williams as "Trumpet Man"

Admittedly, he may have bitten off more than he could chew or do full justice to, even within the course of two and a half hours, and one could fairly argue the film doesn’t do more than skim the surface of its themes of gentrification, racism, and the corrupting effects of power except to the extent that they drive the whodunnit plot. Collaterally, even though there are several key black characters, they feel less like fully developed persons than chess pieces in the unfolding showdown between Lionel and Moses. That’s true of most of the many supporting characters, actually, black or white. A quality cast (that includes, in addition to Baldwin, Bruce Willis, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Michael K. Williams, Jr., Cherry Jones, Bobby Cannavale, and Willem Dafoe) still generally make the most out of their relatively limited material. Dafoe gets the most to work with but does almost too much, bordering on overacting, while Williams gets the most mileage out of the most underwritten role of all, an enigmatic jazz musician who’s literally titled only “Trumpet Man” but leaves a distinct impression.

That said, Motherless Brooklyn really works best as a study of the power struggle between Norton’s and Baldwin’s characters, the stark fundamental contrast between their personas, MOs, and values vividly drawn by two equally different actors. They only have two scenes together, but they both crackle. What struck me most about both performances was their surprising restraint. Although some have compared Baldwin’s Moses to that other politically powerful and unscrupulous bully he’s been playing a lot lately on TV, his Moses is a very different type of operator – more ruthless and more effective at extracting what he wants, with minimum words or fuss, and embodying a relentless, impassive quality Baldwin conveys convincingly in comparatively little screen time. He represents not so much a man as a force – the force of brutal, unchecked power – and a reminder of how easily and callously that kind of power can wreck the lives of those with less or none. That reminder is always timely, perhaps especially now.

As for Norton, a detective with Tourette’s may sound like shameless Oscar bait, and Norton has gotten some flak for his portrayal of the disorder. (My husband actually asked me if Norton had added the Tourette’s to increase his Oscar chances; he didn’t, it’s in the book.) Yet to my eye, he tackles it with grace and aplomb, tempering Lionel’s nervous tics and jagged outbursts with a rueful, humorous self-awareness, and a pervasive gentleness that responds to gentleness in others. There’s a touching moment when he explains to Mbatha-Raw’s character why he likes her and is trying to help her – quite simply, because she’s a nice person who wants to help others. It’s that simple humanity that lends what could have been a standard hard-boiled gumshoe narrative a softer sheen.

Motherless Brooklyn isn’t perfect. It’s at once old-fashioned and overambitious, and in an odd way it reminded me a little of another recent release, Ad Astra, in how openly indebted it is to classic films of its genre, risking being completely obscured by their shadow. By the same token, though, its weakness is also its strength. No, it’s not as good as Chinatown or L.A. Confidential. But it will remind you of them, and if you liked those movies, you should find a lot to like about this one. I know I did.