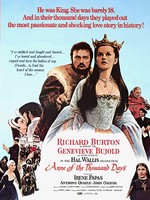

Anne of a Thousand Days (1969) was released 50 years ago today.

Anne of a Thousand Days (1969) was released 50 years ago today.

Even before her famous death, Anne Boleyn had become a legend. I don't say this to aggrandize the historical figure, but to explain that the second wife of Henry VIII had transformed into something not quite human. Legends aren't people so much as abstractions of them, told and retold, morphed by cultural shifts and the interest of those who tell them.

With the birth of cinema, Anne Boleyn would come to be one of the stalwarts of the historical drama on the big screen. Unfortunately, the cycles of empty mythologizing wouldn't end with the advent of new technology. As a character, Anne Boleyn is more often than not a symbol. She's a monstrous harpy or she's a martyred victim, she's a seductress who brought disgrace upon herself or she's an icon who died at the hands of a perfidious tyrant. Even on the rare instance when she gets to be protagonist, rather than a supporting player in another's tale, she's not allowed to be a person with a full characterization. For what it's worth, 1969's Anne of the Thousand Days, at least, tries to do right by Anne Boleyn.

I'm unsure if this is the filmmaker's doing or the singular feat of Geneviève Bujold...

The Québecois actress received her only Best Actress nomination for her performance as Anne Boleyn and it's easy to understand why. Even when her film insists on jettisoning itself into the pits of stuffy costume drama mediocrity, Bujold never lets herself be dragged down. Not by the overlit staginess of the directing and not by the portentous bluster of Richard Burton's Henry VIII. Both actors benefit from the other's presence, letting their different acting styles rub against each other with fiery friction. When Burton savors each line as if it was a juicy lamb chop, Bujold spits out her sharp witticisms like a cannonball. This Henry may enjoy the sound of his own voice but Anne wants to get to the point of the conversation quickly.

It's impossible to say if this interpretation of the historical figures is in any way verisimilar, but it feels real without sacrificing human complexity. In drama, that's sometimes more important than historical fidelity. The rest of the film's production certainly takes that attitude and runs with it. The costumes that won Margaret Furse an Oscar may be pretty and character appropriate, but their accuracy is, at best, debatable. However, it's difficult to begrudge the design of those unconvincing French Hoods when they frame Bujold's face so beautifully, creating a halo that calls attention to her piercing expression.

And oh, how those expressions add color and subtext to scenes. If Anne of the Thousand Days does one thing right is how it always presents its heroine as a self-possessed individual. When the dialogue doesn't show such reality, Bujold's eyes do, shining with intelligence. Anne is always deeply aware of how far she can go and what her prospects are at any given moment. When she's initially reluctant to the king's advances, they're brightened by fury. At the peak of the wooing, she's horny, not for the King but for power. As she falls in love with the man, there's a bigger ease of expression, an abandonment of youthful sprightliness for a more mature calm. Finally, when her fate is sealed, Bujold doesn't let the shadow of surprise mar her face.

This doomed queen is savvy enough to know how the pieces fall on the chessboard. Her theatrics during the trial may smell like the panic of a threatened animal but her tense countenance only shows the aura of carefully curated innocence. Still, it's her two final scenes that bring me to my knees in awed admiration. What she and a saturnine Burton do in their last duet is nothing short of a miracle, playing battling titans too tired to fight. They know what's going to happen and their pithy words are a mere attempt to gain the moral high ground or, more importantly, a sense of autonomy.

When she confirms the King's suspicions, the queen isn't having an episode of madness. She's reclaiming ownership of her fate. Let it not be the plans of others that kill her but the furious lies she spits at her proud husband. For a character whose legacy has been shaped by biased propaganda, this gesture feels so much bigger than the film suggests. At last, as the time of execution arrives, Anne of the Thousand Days gives the viewer one last respite from the usual hysterics associated with this couple. The twilight moments of the queen's life are peaceful if tainted by terror. In the face of death, Bujold maintains the lucidity of her character and her characterization.

It's astounding work and, had she been nominated another year, Geneviève Bujold might have been a worthy winner of the Oscar.