By Lynn Lee

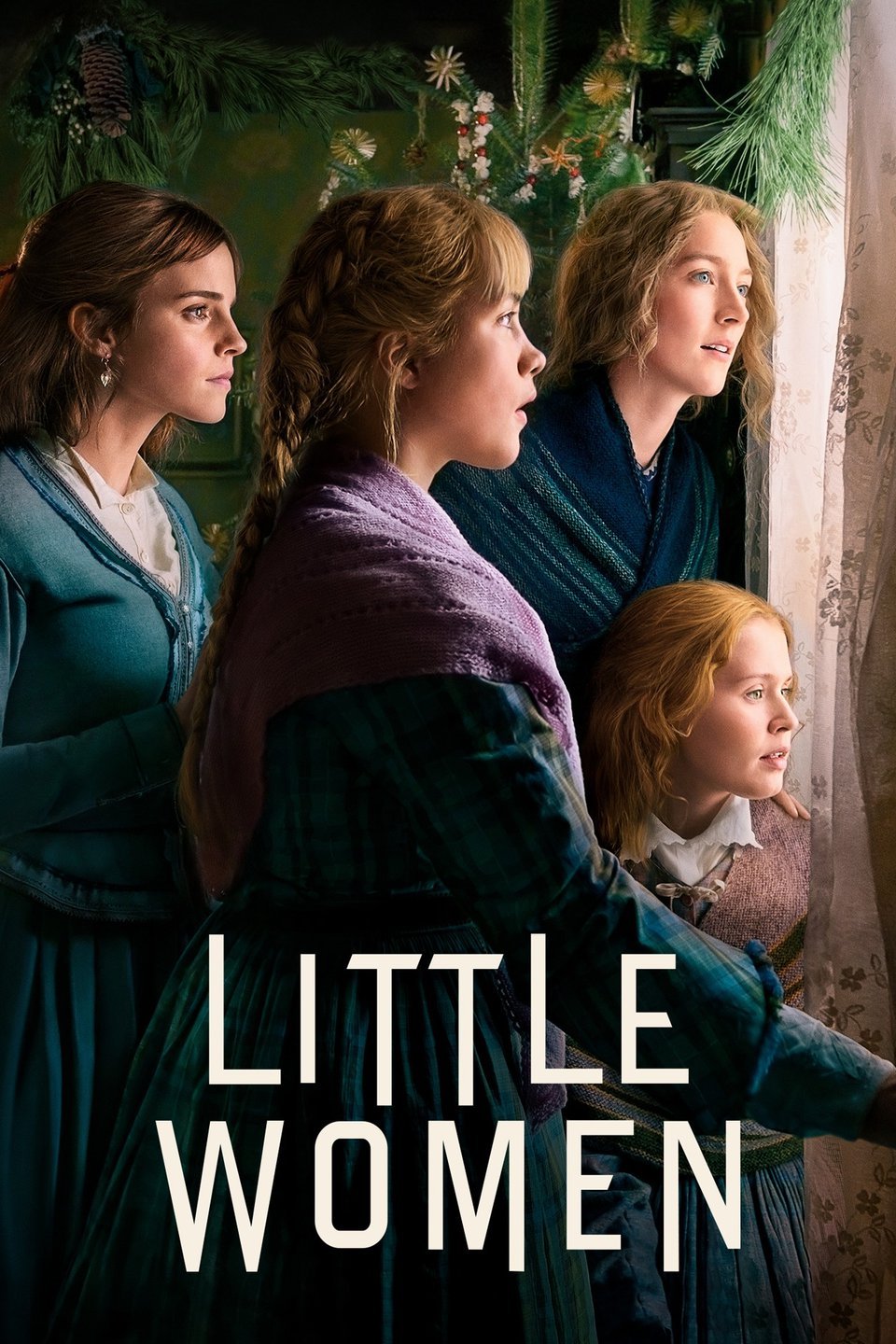

Did we need another one?

Did we need another one?

That question hangs over any movie based on a novel that’s already been adapted multiple times – even more so if there’s a previous adaptation that’s particularly beloved. It may not, however, be the right question. As potential movie material, perhaps great books should be treated more like great plays are for the stage, in the sense that if the work has enduring appeal, every new era deserves its own adaptation. So perhaps the better question is whether this adaptation speaks to us, the viewers of today?

As applied to Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, the answer is yes…with a few caveats. Full disclosure: I came to the movie as someone who read Louisa May Alcott’s coming-of-age classic so many times that my copy literally fell apart at the seams, and my devotion to Gillian Armstrong’s near-perfect 1994 adaptation starring Winona Ryder (which you should absolutely see if you haven’t) is a matter of TFE record .

While Armstrong’s version remains my favorite, I found a lot to like and admire about Gerwig’s...

Greta Gerwig directing Emma Watson

Greta Gerwig directing Emma Watson

It helps that the two films share not only literary but also Hollywood DNA: both are Sony/Columbia Pictures, and Gerwig’s was produced by Amy Pascal, Denise DiNovi, and Robin Swicord, who respectively developed, produced, and wrote the screenplay for the 1994 film. In overall look and feel, the new Little Women is a kindred spirit to its predecessor, even while offering a completely fresh take in both conception and execution.

Essentially, Gerwig takes the well-known story of the four March sisters and shakes it up - literally. She flips the book’s girlhood-to-adulthood chronology on its head and then splices it, reframing the narrative from the grown-up perspective of the second sister and Alcott stand-in, Jo (Saoirse Ronan, terrific), as an aspiring postbellum writer looking back at her and her sisters’ childhood in a series of flashbacks that eventually provide inspiration for her writing. It’s a bold approach that directly challenges LW fans’ tendency to focus on the cozy scenes of the first half at the expense of the sadder, more complicated second half. It also provides a great showcase for cinematographer Yorick Le Saux (the go-to DP for directors Luca Guadagnino and Olivier Assayas), as well as costume designer Jacqueline Durran, who do wonderful work here drawing almost painfully razor-sharp contrasts between the warm colors and lighting in the scenes from the past with the colder, grayer and bluer shades of the present.

That said, the constant shifts in time can be disorienting, especially with four sisters to track, and make the film feel a bit disjointed. They also tend to undercut the emotional impact of some of the more poignant character arcs. Without “spoiling” a 150-year-old book, I’m thinking in particular of the main storyline for Beth (Eliza Scanlen), the quietest of the sisters, and, separately, Jo’s relationship with male neighbor and bestie Laurie (Timothée Chalamet, appropriately dreamy if almost too pretty), the outcomes of which are telegraphed early and often. While the climax still packs a gut punch in both instances, the path feels choppy, its natural momentum interrupted by all the other storylines jostling next to it. This kaleidoscopic, snapshot style worked very well in Lady Bird; I’m not sure it always works for Little Women.

Ultimately, what emerges from Gerwig’s restructuring is an extremely meta narrative about writing and being a woman writer in particular, underscored by the movie’s opening and closing images of physical bookmaking and the narrative framing device of Jo’s negotiations with a skeptical publisher (Tracy Letts) who bluntly advises her that all female characters need to be either married or dead by the end of the story. How Gerwig addresses that prescription as to Jo results in a witty hat tip to Alcott, who herself never married and fumed over having to make Jo do so. It also feels a little too clever by half, like the movie’s trying to have its cake and eat it, too. And it shortchanges Professor Bhaer (Louis Garrel, much too young and attractive for the part) who, like him or not, is one of the few significant male characters besides Laurie in Little Women. He’s still here, but – by design, not accident – registers less as a character than as a cutout.

The professor is, fortunately, the exception to the rule. This Little Women invests loving care in all the other principal players, and the sisters’ roles are more equally weighted here than in other adaptations. The biggest beneficiary is Amy (Florence Pugh), who finally escapes the usual limitations of the spoiled youngest sister role to emerge as a genuinely interesting, even compelling, three-dimensional character. Pugh isn’t obvious casting for the part; I always envisioned Amy as elegant and ballerina-like, where Pugh is sturdy and compact. But she conveys with striking force and conviction Amy’s strength of will, realism, and knowledge of what she wants, which allow her to hold her own fully against Jo.

The professor is, fortunately, the exception to the rule. This Little Women invests loving care in all the other principal players, and the sisters’ roles are more equally weighted here than in other adaptations. The biggest beneficiary is Amy (Florence Pugh), who finally escapes the usual limitations of the spoiled youngest sister role to emerge as a genuinely interesting, even compelling, three-dimensional character. Pugh isn’t obvious casting for the part; I always envisioned Amy as elegant and ballerina-like, where Pugh is sturdy and compact. But she conveys with striking force and conviction Amy’s strength of will, realism, and knowledge of what she wants, which allow her to hold her own fully against Jo.

The cast is filled with acting heavyweights including no less than Meryl Streep hamming it up just enough to have fun as crotchety Aunt March, Laura Dern playing it completely straight as the girls’ kindly Marmee, and Chris Cooper doing a benevolent patriarch 180 from his toxic father in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood. There are also rising stars (Challamet, Scanlen) and Emma Watson as oldest and most conventional sister Meg. Despite the collective formidability, Pugh, next to Ronan, is the standout. Her voice provides an important counterpoint to Jo’s regarding the choices of ambitious women in a man’s world, a theme that still resonates today, and that clearly resonated with Gerwig. The more things change, the more they stay the same – and the more need there is to revisit classics like Little Women.