For the Centennial of one of Oscar's largely forgotten superstars, we asked Team Experience to pick one of her films to watch.

by Paolo Kagaoan

by Paolo Kagaoan

We’ve done centennials here before but this one comes with some degrees of difficulty. It doesn’t help that someone changed her name from Phylis Lee Isley into the whitest name in the world, and that the person who gets more Google results for that name is a curler. As a Canadian I can’t say anything bad about curling, but shouldn't a Best Actress Academy Award winner be on at least equal standing to a Gold medallist? Look up all the women who have had five Oscar nominations and a win (Bancroft, Sarandon, Hepburn, Maclaine, etc...) and imagine the world forgetting them. Explaining Jones to friends is equally difficult, even to people in the film industry who know her second husband's name, David O. Selznick.

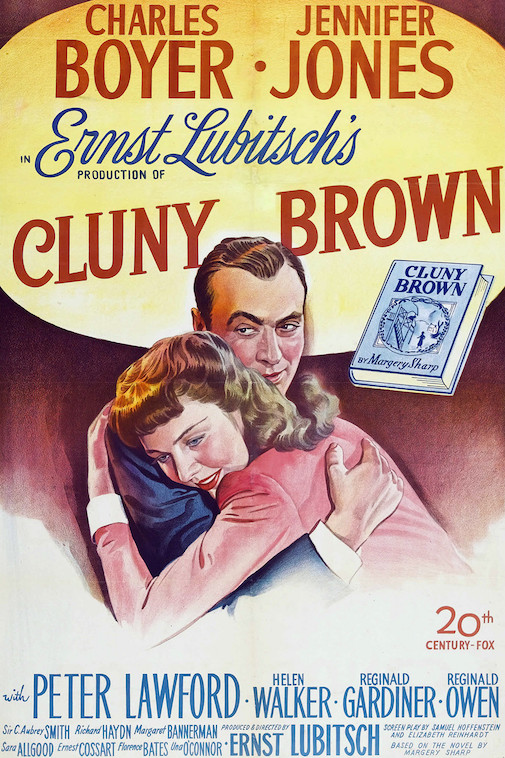

I’d only previously seen Jones in Beat the Devil, a terrible dengue fever dream of a film. And it’s on TV all time instead of films with better reputations like Portrait of Jennie, which is her highest rated film on both iMDb and Rotten Tomatoes. Or Cluny Brown, her film with the highest rating on Letterboxd, and one that also came out the same year as Duel in the Sun (the film that brough her her 4th conseuctive Best Actress nomination) so that's what I picked to watch...

Cluny Brown is the last film that Ernst Lubitsch completed. Convincing audiences that apple pie American actors had European sensibilities is still a subgenre today, but it’s one that Lubitsch perfected. Watching this alone feels like a cheat. It was a moderate box office success, making me wonder how it plays to audiences then and now. Its comedic rhythm and tone, which Jones helps bring to life, are so bizarrely different that I wonder if I’m going to be in a room full of people who get it. Or worse, if I’m going to be the only person laughing in the room and will stop because I’m the only person laughing. And that sense of feeling alone plays into the film’s content, which I’ll explain later.

Instead, I’ll explain the other really strange thing about this film: both of its leads are cast against type. Specifically, I'm talking Charles Boyer, the OG gas lighter, who is probably playing the happiest refugee in film history. He’s no Victor Laszlo. Also starring Peter Lawford, this is also a movie that shows Boyer as a fantasy for women. Sure he’s a bit older and is not Cluny’s type at all, but he’s a guy who understands the world for what it really is without being smug about it. And he’s a white foreigner – women are into that, right? I can be into that.

Charles Boyer in "Cluny Brown"

Charles Boyer in "Cluny Brown"

Casting against type also applies to Jones, who plays the titular role. In Beat the Devil, she’s the smartest person in every scene. Here, playing a female plumber turned maid, she successfully sells the trope of a woman who is smart but doesn't know it. The idea of someone who is oblivious to Britain’s class system is, again, bizarre. It’s also something that the working class characters around her care more about than the aristocracy. I’m not British, thankfully, but I perhaps wrongfully assumed that that country ingrains the idea of ‘knowing your place,’ which is something that some characters tell Cluny.

Cluny Brown, like many comedies, is a film about a society trying to destroy a woman’s soul. Like many class-conscious comedies, mistaken identity comes into play. Jones and Lubitsch expand on the idea to show that social mobility is an idea entrenching itself into Europe. Cluny can walk into a hotel or a manor and have tea and crumpets with the upper crust, savouring those moments before someone of her class points her out and drags her back down.

Again, as unbelievable as it is that a British woman doesn’t ‘know her place,’ we kind of don’t want her to. As an audience and as human, we don’t want to see the destruction of innocence, and neither do we want more people to learn that the world is a terrible place.

Cynics can nitpick her performance, starting from that accent. But the scene when Cluny finally ‘knows her place’ is Jones’ best, showing us a woman’s first heartbreak, reminding us of our own. And watching her here makes us root for her, to get out of that assigned place. May she end up with people who understand her and want her to be the better version of herself.