We're looking back at the 1972 film year before the Smackdown.

by Anna

Peter H Hunt's 1776, based on the stage musical of the same name, chronicles the many woes that went into the Declaration of Independence’s creation. At the forefront of its writing are the “obnoxious and disliked” John Adams (William Daniels), the dry-witted Benjamin Franklin (Howard Da Silva), and the homesick Thomas Jefferson (Ken Howard). Amid the clash of words and egos of the other delegates of Congress, will they succeed?

Recruiting many of the names involved with the original Broadway production (Producer Jack L. Warner’s attempt to atone for casting Audrey Hepburn over Julie Andrews for My Fair Lady), 1776 had the misfortune of being released the same year as another period piece musical.

Would 1776 have won more acclaim had it been released a different year?

Since the stage musical won three Tony Awards (including Best Musical) and the only two awards the film was nominated for – Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy at the Golden Globes and Best Cinematography at the Academy Awards – both went to Bob Fosse’s Cabaret, it’s more than likely.

The musical was also released during a time of high political tension within the United States. One song in particular didn’t sit well with then-President Richard Nixon. He saw it as a barbed attack on his conservative viewpoints and asked Warner, a friend and supporter, to cut “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” from the film. Nixon had previously (and unsuccessfully) tried to stop the Broadway cast from performing it at the White House. Hunt was willing to cut out other jabs at right-wing politics because their absence wouldn’t affect the story but removing “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” would. In the end, the song was cut from the final theatrical product. The footage wasn’t destroyed as Nixon requested because Warner wasn’t in the power to do so; Co-editor Florence Williamson had stowed away the intact footage which was later restored for DVD. According to Hunt, Warner would regret his decision. On his deathbed, Warner reportedly told a friend: “I should have never listened to that idiot Dick Nixon!”

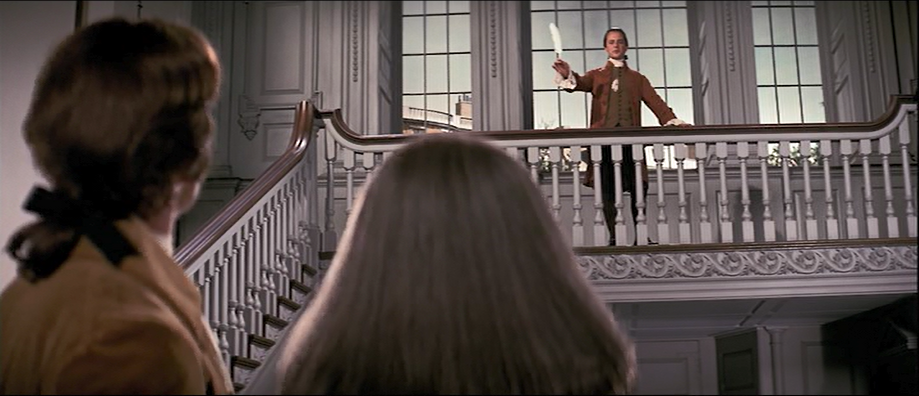

William Daniels as John Adams and Blythe Danner (in just her second film) as Martha Jefferson in "1776"

William Daniels as John Adams and Blythe Danner (in just her second film) as Martha Jefferson in "1776"

If you've never seen 1776, don't think that just because it’s set in the 18th century, it will be prim and proper. The musical is way bawdier than one would initially expect, though it’s probably inevitable when the cast is predominately male. (“I’ll stop at Stratford just long enough to refresh the missus, and then straight to the matter!”) It’s particularly prevalent with Adams and Jefferson, both of whom long for their wives; Jefferson suffers from writer’s block until his wife Martha (Blythe Danner) shows up in Philadelphia (that didn’t happen in real life) while Adams’ cross demeanor is implied to be the result of being away from his wife Abigail (Virginia Vestoff) for too long (that was lifted from an early letter Adams wrote to Abigail). And let’s not get into the New Brunswick dispatch…

Some anachronisms and artistic liberties aside, 1776 is actually very thorough in its depictions. It certainly didn’t hurt that Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards were the son of a former history teacher and a history teacher, respectively, before they wrote the original stage musical. Much of the dialogue (such as the “unalienable” vs. “inalienable” squabble between Adams and Jefferson) and some of the song lyrics were lifted verbatim from the writings of the various members of the Second Continental Congress. Adams’ duets and discussions with Abigail were derived from their personal letters. Granted, there were some elements Stone and Edwards purposefully kept out of the final product.

To quote the footnotes in the Penguin Plays edition:

“…by far the most frustrating reason for deleting a historical fact was that the audiences would never have believed it. The best example of this is John Adams’ reply (it was actually Cousin Sam who said it) to Franklin’s willingness to drop the anti-slavery clause from the Declaration. “Mark me, Franklin,” he now says in Scene 7, “if we give in on this issue, posterity will never forgive us.” But the complete line, spoken in July 1776, was “If we give in on this issue, there will be trouble a hundred years hence; posterity will never forgive us.” And audiences would never forgive us. For who could blame them for believing that the phrase was the author’s invention, stemming from the eternal wisdom of hindsight? After all, the astonishing prediction missed by only a few years.”

Mind you, in stark contrast to its run on Broadway, the film wasn’t as well-received as it is now. Roger Ebert deemed it “an insult to the real men that were Adams, Jefferson, Franklin and the rest”. (Vincent Canby in turn called it “the first film in my memory that comes close to treating seriously a magnificent chapter in the American history.”) And why would anyone pay to see a movie about the Founding Fathers, let alone a musical on them? Nowadays in this post-Hamilton world that we live in, we can appreciate what Stone, Edwards and Hunt have given us. And with the 50th anniversary of the play’s Broadway debut last month (and Edwards’ centennial earlier this month), that give you more of a just reason to seek this out before the Fourth of July.

Oh, and word of caution: one of the songs will invariably get stuck in your head.