Michael Cusumano here to christen my new series on future classics of the 21st Century with Tony Gilroy's 2007 legal thriller. In each episode we'll be discussing one great scene.

The Scene: Karen Crowder’s Downfall

How does the final scene of Tony Gilroy’s Michael Clayton work so well despite the wheezy cliché at its center? Secretly recording the villain’s confession is right up there with the Monologuing Killer on the list of tired plot devices. Yet when Clooney coerces Swinton into exposing her sins it doesn’t feel the least bit lazy. On the contrary: it’s electrifying...

Part of it is how elegantly Gilroy’s screenplay sets the stage for Karen’s ruin. Typically, when writers wheel out this trope, it’s a cheap escape hatch out of a screenplay’s third act. Not here, where we understand perfectly the dynamic at play. Karen is this closeto getting away with everything, the lawsuit over her client’s carcinogenic weed killer, the murders she ordered on Tom Wilkinson’s whistle-blowing attorney and George Clooney’s corporate fixer, all of it. She is probably beginning to let a little relief creep in when --BOOM-- Clayton shows up back from the dead with a fistful of damning evidence and a room full of stockholders twenty feet away. Even the steeliest criminal might falter under such circumstances and as we’ve seen, Karen is far from the corporate master of the universe she plays at being.

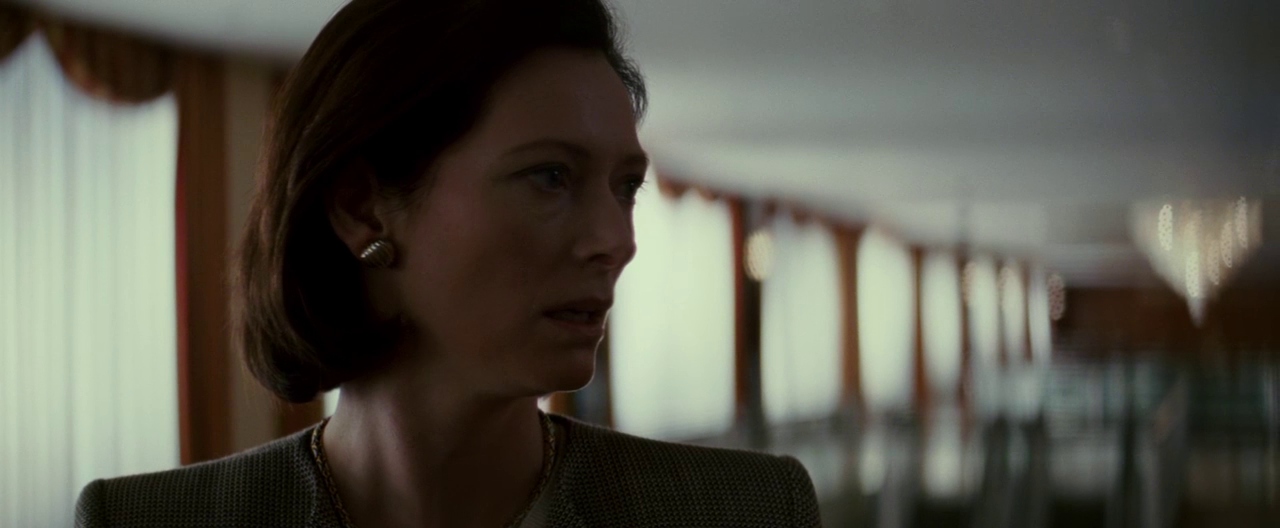

When an antagonist incriminates him or herself, arrogance is usually the fatal flaw. Think Colonel Jessup blurting out a confession in A Few Good Men or Gordon Gekko raging at Bud Fox in Wall Street. Not with Karen Crowder. For the whole film we’ve watched her barely hold it together, hiding in the ladies’ room, mopping up pit stains, desperately hoping she can sell off the last shreds of her soul before anyone spots the nervous wreck behind the frumpy gray business suit. She orders the hit on Tom Wilkinson with all the confidence of fourteen-year old buying beer with a fake ID. Having her flimsy façade crumble in a moment of stupid panic is the perfect comeuppance, like the final inevitable beats of a Greek tragedy.

In many ways Michael Clayton acts as Karen’s mirror image in this scene. Like her he spends most of the story excusing his compromises and rationalizations for the sake of expedience. Now haven finally rejected his own façade, the idea that he is anything but the “bagman” Arthur labeled him, he can wield that persona like a weapon. “I’m not the one you kill. I’m the one you buy,” he says reeling Karen back in when her instincts correctly tell her to flee. The film has earned the suspense that the story might go for the cynical ending, the one in which Michael sells out for the opportunity to escape because justice is not a possibility in such a corrupt world.

Off course, none of this would be half as effective without Swinton’s flat-out brilliant performance. This scene lasts just over four minutes and in that time we feel every excruciating step in Karen’s disintegration. There are so many devastating choices, like the way she tries and fails to cling to the appearance of confidence by laughing off Clayton’s ten-million-dollar demand, or her delivery of “You don’t want the money?”, a line that might have felt like too blunt a thesis statement were it not for the pathetic childlike confusion in her voice. Shaking in terror and collapsing are two things that almost always read as fake on screen but here Swinton makes you believe it. The way she allows the weight of her realization to sink in, followed by her legs buckling and an attempt to balance herself against the floor. It’s so much more effective than the standard melodramatic swoon.

Movies with corporate villains tend to portray them as omnipotent as Orwell’s Big Brother. In Michael Clayton, Gilroy associates them symbolically with weeds. Destructive not in their in their power but in their relentlessness, their ubiquity. It’s no coincidence that Arthur Edens, the film’s mad prophet, repeatedly translates the coldly corporate in terms of the organic, converting his billable hours into a percentage of his life, or imagining the law firm itself as a gigantic living organism. In this, Michael Clayton suggest that the real power is in seeing these monolith corporations as human and fallible. How fitting then that in the end, the entirety of U North’s years-long, billion-dollar defense goes under because Karen Crowder can’t spot an obvious ploy when it’s right in front of her face.