by Eric Blume

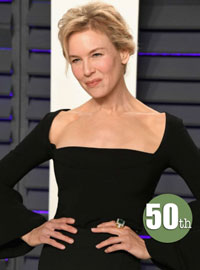

It seems crazy, but today marks the 50th birthday of Oscar-winning actress Renée Zellweger. Zellweger is a bit of a divisive actor (even within this site!), but I loved her the second I first saw her onscreen, loved her through her big decade of success, and will proudly love her forever.

It seems crazy, but today marks the 50th birthday of Oscar-winning actress Renée Zellweger. Zellweger is a bit of a divisive actor (even within this site!), but I loved her the second I first saw her onscreen, loved her through her big decade of success, and will proudly love her forever.

I fell for Zellweger for the first time the way most of America did: as assistant Dorothy Boyd opposite Tom Cruise in Jerry Maguire in 1996. Even though that film features Cruise’s best performance (he should have beat Geoffrey Rush for the Oscar), I walked away from Jerry Maguire thinking, who the hell is Renée Zellweger? It takes major presence and considerable skill to not be blown off the screen by a star like Cruise at his most commanding. Not only did Zellweger hold her own, she brought out new things in him: a comic warmth, a quality of genuineness, something softer and more open. He listened to her and didn’t anticipate everything, because she was off-center...

Zellweger took the role of “The Girl” and made her complete: she was a young mother who didn’t know what she was doing, someone desperately looking for inspiration who makes a gut, “foolish” decision because she was defining who she was. Zellweger wrung truth out of Cameron Crowe’s idealized girl and made her a living, breathing human, something complex and interesting in a very commercial movie not actually centered on her character.

Two years later, she went up against another heavy-hitter, Meryl Streep herself in Carl Franklin’s 1998 film One True Thing. This film is a seriously underrated gem, in which Zellweger once again more than holds her own against Streep and one of cinema’s other great actors, William Hurt. Meryl got the Oscar nomination, but Zellweger is in control and never lets the film stray from her character’s arc: the beauty in the film is in watching her character lose respect for her revered father while she gains respect for her marginalized mother, and the actress calibrates it very wisely. We watch her go through a series of realizations, then rationalizations, then crystallizations on her parents’ character. Then we watch her pull it all together through a change that feels honest and earned.

I maintain that Zellweger’s performance in 2001’s Bridget Jones’s Diary is sheer perfection. Zellweger finds comic bits within beats. She walks funny. She wears clothes funny. She burrows into Bridget’s messy, thoughtless, brazen heart and is so deep in character that we feel we’ve never seen her before. There isn’t an ounce of comedy in that script that Zellweger doesn’t find, and she doesn’t shy away from the uglier aspects of the character either. It’s because Zellweger makes Bridget so very, very specific that she turns out to be every single person who has ever put themselves out there to love another person.

I maintain that Zellweger’s performance in 2001’s Bridget Jones’s Diary is sheer perfection. Zellweger finds comic bits within beats. She walks funny. She wears clothes funny. She burrows into Bridget’s messy, thoughtless, brazen heart and is so deep in character that we feel we’ve never seen her before. There isn’t an ounce of comedy in that script that Zellweger doesn’t find, and she doesn’t shy away from the uglier aspects of the character either. It’s because Zellweger makes Bridget so very, very specific that she turns out to be every single person who has ever put themselves out there to love another person.

The next two years brought the one-two punch of Chicago and Cold Mountain, which finally won her the Oscar. In Chicago, Zellweger gives a humdinger of a performance for someone who cannot really sing or dance yet is starring in a musical. Zellweger tears into Roxie Hart the same way Roxie Hart tears into the world: by sheer ugly force. Her Roxie has a limited talent, and the strident singing and just-getting-by dancing serve the character well. It’s a nice contrast (and superior to, in my opinion) Catherine Zeta-Jones’ military-like showmanship as Velma, and Zellweger keys herself into a stylized musical theater notch from beginning to end that helps the movie stay comic and self-aware, two ingredients key to that particular musical’s success.

Boy am I going to hear about it in the comments section, but I even think she’s wonderful in Cold Mountain. Yeah yeah yeah, it’s cornpone. Sure, it’s shockingly unsubtle and crude. But I’d argue it’s exactly what Cold Mountain needs: force and energy. When Renée trudges into the movie about 45 minutes in, the entire picture lifts. It breaks out of its romantic spell and gets a new jolt of... something. That something is not something to many peoples’ liking, but the movie would have died without her, drowning in self-seriousness. I could feel Zellweger’s love for that character, and she made me laugh. As with so many performers, she didn’t win the Oscar for one of her best performances, but I’m glad she has one.

In addition to these big films, she’s also been dry and offbeat in Neil LaBute’s Nurse Betty; juicy as part of the dynamic blond troika of White Oleander; tender opposite Vincent D’Onofrio in The Whole Wide World; and sexy and stylish in Down with Love. This all adds up to a lot of great onscreen work.

And so we wait to see how her big “comeback” will be when she plays Judy Garland later this year. It’s a performance that could be remarkably inspired or go down as a colossal mistake. I'm guessing even if the movie doesn’t deliver, Zellweger will try something interesting.

Zellweger is one of those special movie creatures who have the intangible: magic. There are actors like Jodie Foster and Emma Stone and Zellweger who are so truly unique, so completely special, that they feel born for the camera. They don’t come from traditional acting backgrounds and arrive with little training, yet the camera takes to them, and them to it. There’s no explanation for it, and that’s the beauty of it.

Zellweger has genuine moxie, not a trait highly valued in our contemporary cinema, but one that is essential to it. I’m so grateful to her for her enormous talent, and all of us here at TFE wish her a very happy half-century.