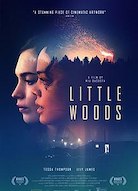

by Tony Ruggio

Little Woods, North Dakota: not far from our border to the north, and a poster child for the death of the American Dream. Tessa Thompson is Ollie, a woman hardened by a life selling oxy and a an allergy to hope. Her adopted mother has passed and she and her younger sister Debbie (Lily James) are left to pick up the pieces, namely a pittance of a house and what’s left of Ollie’s former life. She’s nearing the end of her probation and you know what that means. Life’s about to throw her a curveball, sending her back to the wheelin’ and dealin’ trenches, where seedy characters and searing guilt are part of the job. Debbie needs help and Ollie’s good at doing, so she’s back at it to pay the mortgage and get her sister the medical care she needs. It’s all very predictable, but it hardly matters...

Little Woods, North Dakota: not far from our border to the north, and a poster child for the death of the American Dream. Tessa Thompson is Ollie, a woman hardened by a life selling oxy and a an allergy to hope. Her adopted mother has passed and she and her younger sister Debbie (Lily James) are left to pick up the pieces, namely a pittance of a house and what’s left of Ollie’s former life. She’s nearing the end of her probation and you know what that means. Life’s about to throw her a curveball, sending her back to the wheelin’ and dealin’ trenches, where seedy characters and searing guilt are part of the job. Debbie needs help and Ollie’s good at doing, so she’s back at it to pay the mortgage and get her sister the medical care she needs. It’s all very predictable, but it hardly matters...

In their neck of the woods, hospitals run up seven-hour waits and week-long delays, so hardhats and truck drivers can’t get the care they need. When they’re not nursing their wounds at a local roadhouse they’re nursing them at home with pill mills and anything else. Nia DaCosta’s little film is a big deal, being the only film brave enough to fully address the opioid epidemic, only without going full Traffic. I had recollections of Winter’s Bone and Leave No Trace, part of a growing sub-genre of “women in the woods,” where young female protagonists offer a different take on man vs nature and on the young forced to grow up too fast in a slow world. Like those earlier films, Little Woods is steeped in sub-cultural detail and stark realism, even if it occasionally succumbs to misery porn.

Thompson is reliably stoic as a fierce survivor of these woods, but the surprise is Lily James who reveals a subtlety and depth of feeling heretofore undiscovered. Her Debbie is a young woman unable to get out of her own way, often relying on her big sister to bail her out of trouble or her surly, drunken babydaddy (James Badge Dale) to boost her confidence. She and her six year-old son live in a van in a supermarket parking lot, alongside others under threat of tow trucks. Like everyone else, she’s a victim of her surroundings. There ain’t no abortion clinic for hundreds of miles and jobs are in scarce supply. They’re all living in a town abandoned by modernity, progress, and the country at large, save internet access of course.

That’s where Canada comes in. Little Woods subverts the outdated notion of American exceptionalism by showing people struggling, smuggling their way across the northern border. For healthcare and other means, these people risk life and freedom to trek across thick brush and harsh terrain. Note the cloudy pall hanging over any scene in the States, the grey, black, and muted browns, and contrast it with Winnipeg, Canada, where the sun is shining and there’s real color for the first time. Our neighbor to the north is their city on a hill, their beacon to a better life, at least temporarily. DaCosta’s film is at its best when allowing Lily and Tessa to play off one another, weighing their actions and reactions to hard decision-making, the kind they’ve been making every day of their lives. More than abortion or oxy crises, Little Woods is about sisterhood in the face of adversity, and these two knock it out of the park. B

Little Woods is now playing in select theaters.