by guest contributor Alfred Soto

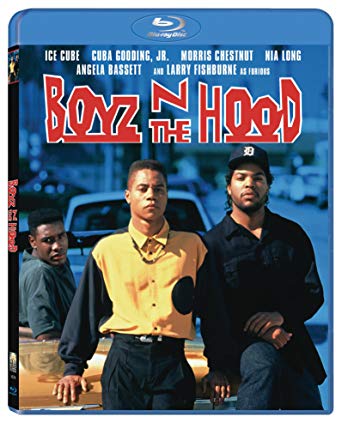

Few young filmmakers get their scripts approved and direct a film in which most things go right, and John Singleton did with Boyz n the Hood. The 1991 depiction of life in blighted South Central L.A. starring a mesmerizing Ice Cube became the kind of phenomenon that absorbs cultural currents and creates new ones; for a few years pop music and MTV took their cues from Boyz n the Hood. It made $60 million and, in one of the Motion Picture Academy’s occasional gob-smacking beau gestes, earned Singleton a Best Director nomination, the youngest in history and, more crucially, the first nomination for a black director.

Please consider the times...

George H.W. Bush was in the White House. He nominated (and the Senate confirmed) Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Weeks after the 64th Academy Awards, South Central went up in flames. To be Jackie Robinson and Sidney Poitier, and, for different reasons, Elton John in their times led to moments when reckoning with the intersections of audience prejudices and the same audience’s expectations must have felt soul-crushing. In the years after Boyz, Singleton aimed smaller, willing himself, it seems, to retreat from importance; he was besotted with a different kind of importance.

George H.W. Bush was in the White House. He nominated (and the Senate confirmed) Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Weeks after the 64th Academy Awards, South Central went up in flames. To be Jackie Robinson and Sidney Poitier, and, for different reasons, Elton John in their times led to moments when reckoning with the intersections of audience prejudices and the same audience’s expectations must have felt soul-crushing. In the years after Boyz, Singleton aimed smaller, willing himself, it seems, to retreat from importance; he was besotted with a different kind of importance.

Poetic Justice (1993), thanks to the casting of peak-career Janet Jackson and comer Tupac Shakur, makes fine use of beautiful black bodies and, rarer, showed these same characters loving words, savoring poetry. Although the picture had a remoteness and often stranded Jackson (Singleton had problems writing female characters), it was fresh in its appropriation of road movie tropes. Worse, though, was Higher Learning, which in 1995 already played like a sixties PSA against marijuana use. Each campus stereotype gets an airing, staged so that Rush Limbaugh could stop the movie on air and denounce the perfidy of PC culture. Teachable Moments for everyone!

Regina King and Janet Jackson in "Poetic Justice"

Regina King and Janet Jackson in "Poetic Justice"

Before turning to Shaft (2000), 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003), and other work-for-hire (some of it not bad; Shaft deserves a second look), I would submit Rosewood (1997) as his most fully realized picture: Boyz n the Hood re-conceived during the Harding administration at the height of the Ku Klux Klan revival, with the whites leading the ambush against what Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in his new Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow, called the New Negro’s self-sufficiency, “capable of his own upkeep and uplift.” Also: a film about white violence without uplift; racism isn’t a “problem” to be overcome, it forms part of a continuum.

Baby Boy (2001), his last film from his own script, returned to contemporary black life with a raucousness that belied its occasional moralizing. And what a cast! A young Taraji P. Henson killing it. Tyrese and Snoop Dogg doing their own Laurel and Hardy thing.

Taraji P Henson in "Baby Boy"

Taraji P Henson in "Baby Boy"

After the huge, anonymous success of 2 Fast 2 Furious, Singleton kept going — he had no choice. Something called Four Brothers (2005) starring Mark Wahlberg, Tyrese again, and Andre Benjamin came out with his name attached; I haven’t watched it, several friends have recommended it. Remember Taylor Lautner? Singleton directed something with the Twilight star on whose poster Lautner looks properly terrified, as if watching the crumbling arc of a career.

Only hacks would say Singleton’s career amounted to unfulfilled promise, not when every film before 2 Fast bears his peculiar brand of hysteria and quietness. It would also be a claim suffused with racism — who says he wasn’t in control of his destiny? Poitier got the same accusations. Examining Singleton’s work will reveal no incontestable masterpiece; its breadth of interests, his I’ll-try-anything-once approach may have disappointed critics who praised the youngest, blackest nominee in Oscar history. An artist in a medium that rewards the loyal journeyman, often by awarding him a Best Director prize, Singleton acted as if a journeyman approach was inseparable from his artistry. For a while Singleton was uneven on his own terms — those are the only terms, to misquote the young feller whom Singleton displaced in the stats, anybody ever knows.

Alfred Soto is an instructor of journalism, a media adviser at Florida International University, and freelance editor for SPIN Magazine. He was features editor of Stylus Magazine. His work has appeared in Billboard, The Village Voice, The Miami Herald, NPR, Rolling Stone, Slate, and Pitchfork. Much of his film, art, and political writing is found at Humanizing the Vacuum. He has been a member of the Florida Film Critics Circle since 2015. He lives in Miami. Follow him on Twitter.

Alfred Soto is an instructor of journalism, a media adviser at Florida International University, and freelance editor for SPIN Magazine. He was features editor of Stylus Magazine. His work has appeared in Billboard, The Village Voice, The Miami Herald, NPR, Rolling Stone, Slate, and Pitchfork. Much of his film, art, and political writing is found at Humanizing the Vacuum. He has been a member of the Florida Film Critics Circle since 2015. He lives in Miami. Follow him on Twitter.