by Mark Brinkerhoff

by Mark Brinkerhoff

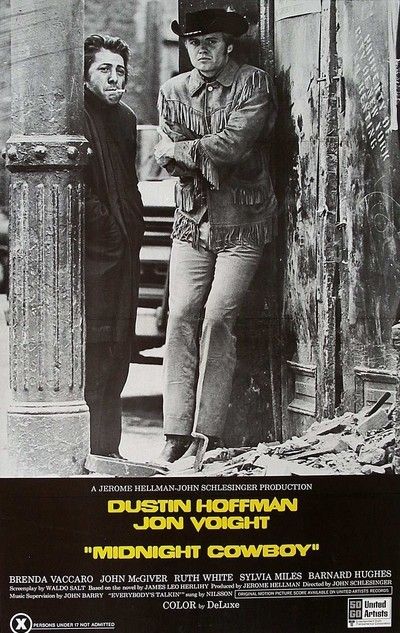

Gay pride month is nearly upon us, so what better time to revisit Midnight Cowboy, the first LGBT-related Best Picture Oscar winner, which arrived in theaters 50 years ago this week. It remains, incidentally, the only X-rated film (for “homosexual frame of reference" and its "possible influence upon youngsters”) ever to win the Academy’s top award.

Centering on Joe Buck, a wannabe hustler from Texas who finds himself entirely out of his depth in the big city (New York, that is), Midnight Cowboy succeeds poignantly, in the words of its director, as an “exploration of loneliness.” It also doubles as — and doubles down on — disastrous toxic masculinity: how men often are conditioned to (mis)treat others, not to mention themselves, as disposable, degradable objects of disaffection.

In this ambling story, callousness reigns supreme, with humanity increasingly lost in the constant shuffle, on the streets of Manhattan...

It can be a brutal sit, but also one worth applauding for how rarely we get to see how the prison of one’s own psyche/psychological trauma can feel, interminably, like a life sentence; so much so that physical death may be welcomed as a bittersweet form of salvation. (We’ll get to that later.)

This immortal line (pictured above), purportedly ad-libbed by Dustin Hoffman as the squirrely Enrico Salvatore “Ratso” Rizzo, occurs early on in the film, once Joe (soulfully played by then-newbie Jon Voight) has aligned himself with the two-bit crook/cripple. It may as well function as the clarion call of Midnight Cowboy, the fight to be seen by our modern-day urban society that long since has given up the pretense of really caring about fellow man’s well-being in any meaningful way.

The film’s metaphorical shots are seemingly endless. When Joe stumbles upon a besuited man splayed out on the sidewalk in front of Tiffany’s, it invites myriad, alarming questions. Did he drop dead of a heart attack? Did he merely pass out? Did he jump out of the building above?! And why is no one, pedestrians just leisurely walking by, stopping to help or check on him? It’s a bracing scene and Joe, the cowboy-channeling, aspiring prostitute, clearly has yet to realize, at this juncture, that keeling over on or getting hit while crossing the street are the least of his worries. The odds of “success” already are stacked woefully, mercilessly, against him.

Has any out-of-the-gate movie star had as lanky, hunky, yet lugubrious and oddly discomfiting a physical appearance as Voigt? Beyond his sheer outsized facial features (famously inherited—and super-sized—by his superstar daughter), Voigt brings a potent physicality, at times strutting and lumbering across the frame. What it must have been like, in 1969, to see that kind of face, that screen presence, for the very first time. He’s bracing, and perfectly cast, as is Hoffman in his scene-stealing, borderline supporting role. Ratso is seemingly the trickier part, one that demands a go-big-or-go-home approach which Hoffman certainly delivers. In sharp contrast to both his star-making debut in The Graduate, and the more internalized, subdued choices of his co-star, Hoffman gets to chew scenery while gradually settling in to the interiority of a character that screams character! from the word go. I find myself less put off and more enthralled by the performance on each rewatch.

Peppered with hey-it’s-that-guy debut performances (M. Emmet Walsh, a stealthily hot Bob Balaban), Midnight Cowboy covers a lot of ground for its time—and not just on account of all of the aimless walking Joe does throughout the city. There is scene after scene of both the dregs of and high society, a fantasia of drug-fueled orgies and lame attempts at hustling world-weary or hapless people with nothing to give and nothing to lose.

It’s easy to forget (if one remembers at all) what a truly scary, scary place New York City had become (well, certain parts at least) by the mid- to late ‘60s. Sure, ‘70s- and early ‘80s-era New York gets a fair amount of treatment in shows like The Deuce, but the by-gone seedy, dangerous Times Square depicted here is only half of it. Midnight Cowboy, like The Panic in Needle Park two years later, takes us down (or up) to the less-trafficked but more hellish neighborhoods and burned-out, derelict buildings where squatters like Joe and Ratso sought shelter.

Switching gears, let’s acknowledge its actresses actressing wonderfully in memorable, narrative-shaping ways. Sylvia Miles appears briefly as a street-wise, would-be client of Joe’s (scoring an Oscar nomination, no less), while a glam Brenda Vaccaro seduces Joe into the aforementioned orgy, representing a halcyon figure with the kind of hedonistic, luxe life that Joe foolishly assumed would be made easily available to him on arrival. How wrong he was.

It perhaps can’t be overstated how much of this masterpiece is attributable to director John Schlesinger. Having demonstrated avant-garde taste and an inclination toward provocative, challenging material with the preceding Billy Liar, Darling (one of my all-time favorite films), and Far from the Maddening Crowd—all starring Julie Christie, who became an Oscar-winning star as a result—Schlesinger’s later filmography sputtered unfortunately into rote thrillers (Eye for an Eye, Pacific Heights) and outright disasters (The Next Best Thing). But—but!—there’s no denying his steady hand with and sensitive direction of Midnight Cowboy, with its quite radical narrative that easily could’ve gone off the rails (again, and again, and again). Good source material, which James Leo Herlihy’s 1965 novel most certainly is, can only get a movie adaptation so far, and Midnight Cowboy benefits significantly from Waldo Salt’s not-entirely-faithful-to-the-book screenplay.

In all, Midnight Cowboy received seven Oscar nomination, winning three for screenplay, directing and the picture—a groundbreaking win a year after the only G-rated film (Oliver!) won Best Picture. (The late ‘60s were a wild time even at the Oscars.) Curiously missing from its nomination count, however, is John Barry’s incredible score, namely the evocative main theme featuring Toots Thielemans on harmonica—does anyone know if it was somehow ineligible?!—as well as Harry Nilsson’s classic song, Everybody’s Talkin’.

Whether hobbling over bridges, limping in underground tunnels, wandering through cemeteries, or, in a desperate, last-ditch effort seeking a “better life,” Joe and Ratso remain joined at the hip, till death do they part. And, for the pneumonic Ratso, death comes quietly, calmly, on a bus bound for the envisioned fantasy land of sunny Florida, his and Joe’s (ill)fates tested and (mis)fortunes spent. For neither a happy ending, only (for one) an ending; maybe (for the other) a tiny sliver of hope that, this time, things might be different.

Midnight Cowboy is streaming now on Amazon Prime.