Michael Cusumano here to thank you for making this post part of your own personal Mike Mills film today. I'm honored.

image via "books in movies"

image via "books in movies"

To watch a Mike Mills movie is to continually ask, “Why don’t more people make movies with this much freedom?”

His films deploy everything from news clips to rotating narrators to archival footage from a century ago. The screenplay will jump backwards in time, skimming through the characters’ biographies, or forwards to glimpse the details of their death. The focus can zoom in to the most granular details or out to encompass the entire cosmos. I doubt he will ever make a film that doesn’t include a shot of the stars. At least I hope he doesn’t...

His films don’t march in a straight line in the standard fashion. They circle the moment, letting it breathe and unfold at its own pace, moving on only after hitting on a moment of truth. It’s an endlessly compelling way to move through a story.

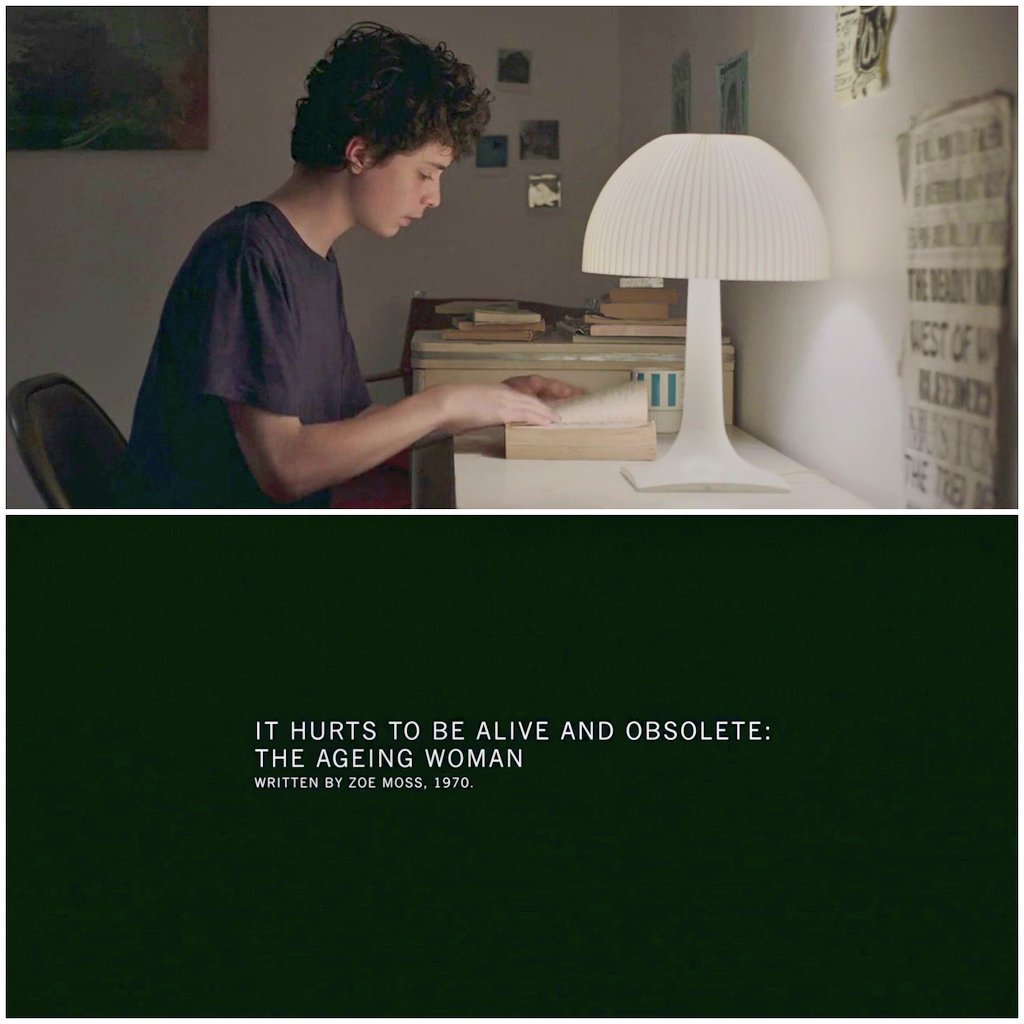

In 2016’s magnificent 20th Century Women, one of Mill’s most effective tricks is to delve into whatever literature the characters are reading. Not just a shot of the covers but big chunks of the text, read in voiceover by the characters. "Forever" by Judy Blume, "The Road Less Traveled" by M. Scott Peck, and in perhaps the most memorable moment in a film full of memorable moments, the essay “It Hurts to Be Alive and Obsolete: The Aging Woman” by Zoe Moss:

…Don’t pretend for a minute, as you look at me that I’m not as alive as you are, and I do not suffer from the category of which you are forcing me…

Fourteen-year-old Jamie (Lucas James Zumann) received this and a pile of other feminist literature from Greta Gerwig’s Abbie after she was instructed by Annette Bening’s Dorothea to take an active part in the raising of her son. Now Jamie sits on her bed reading it to her and she looks truly uncomfortable with what she has unleashed.

Earlier in the film Dorothea encourages her son to be present for Abbie as she deals with the fallout from her cervical cancer, an attempt to teach him a version of the “attention = love” lesson from Gerwig’s own Lady Bird. As he directs that same attention back at his mother we in the audience are primed to believe, as Jamie clearly does, that the reading will be greeted as an insightful description of her. The film implies as much by pairing the essay with a montage of her middle-aged existence. So we are as caught off guard when Jamie is met not with a pat on the head for being a good little feminist, but with hostility instead.

The screenplay says that Dorothea becomes angry, but Bening makes the wonderful choice to play it all with an indulgent smile. “You think you know me better cause you read that?” she challenges. He retreats. “I don’t need to read a book to know about me.” she fires at him before Jamie flees the scene altogether.

Bening’s reaction is fascinating in its complexity. On one level she is offended by her son’s presumptuousness. Jamie is seized by the excitement of grasping difficult adult concepts for the first time, but youthful enthusiasm doesn’t excuse the glib assumption that he has his mom figured out after one night with an anthology of feminist essays. While the writing surely has some sting of recognition, we’ve already seen that Dorothea is too multifaceted to be so easily encapsulated.

And yet, while her son’s behavior rankles, Dorothea’s reaction isn’t entirely pure either. By this point in the film her attempts to relate to the youth of 1979 have left her feeling alienated both from her boy and the culture. Now she finds her son sitting on the edge of her bed holding a copy of “The Politics of Orgasm”. No surprise that she reacts defensively.

On yet another level, the scene could be read as a Mills writing a rebuke of his own film, a reminder directed at his own on-screen stand-in that as lovingly rendered as Dorothea may be, she is still Mills’ version of his parent, filtered through his memories.

That Bening captures all this and a dozen more layers in a few seconds of listening is miraculous screen acting.

"The New Classics"

a series reflecting on great scenes, films, and performances of the 21st century

- Y Tu Mama Tambien (2001)

- Sexy Beast (2001)

- Collateral (2004)

- Eastern Promises (2007)

- Michael Clayton (2007)

- Happy-Go-Lucky (2008)

- A Separation (2011)

- Blue Ruin (2013)