Michael Cusumano here to mark the 10th anniversary of one of the great political satires.

Scene: The Meditation Room

The political operators of Armando Iannucci’s In the Loop live in a world where issues don’t matter and the halls of power are filled with bureaucrats who would gleefully sell out their principles were they not held back by their own incompetence. In this universe, those sad few officials who do manage to take a moral stand are not merely defeated but negated entirely, their feeble protests turned into absurd jokes and swept away in a sea of media noise.

I should add that In the Loop is one of the funniest movies of the 21st Century, but then it would have to be to get away with painting a picture so grim...

Across this cynical landscape, wielding profanity like Leatherface wields a chainsaw, strides Malcolm Tucker, one of the great comic creations, played in a God-level performance by Peter Capaldi. Tucker was once described on The Thick of It, the BBC show that spawned the character, as having the “political instincts and physical bearing of a velociraptor”. It doesn’t feel like hyperbole.

Tucker is a political operative who spends the film pushing for the war, but we sense he could switch on a dime and be equally vociferous against it. The substance doesn’t matter. There are political victories and his ability to obtain them. Characters react to his arrival like someone tossed a live grenade in their laps.

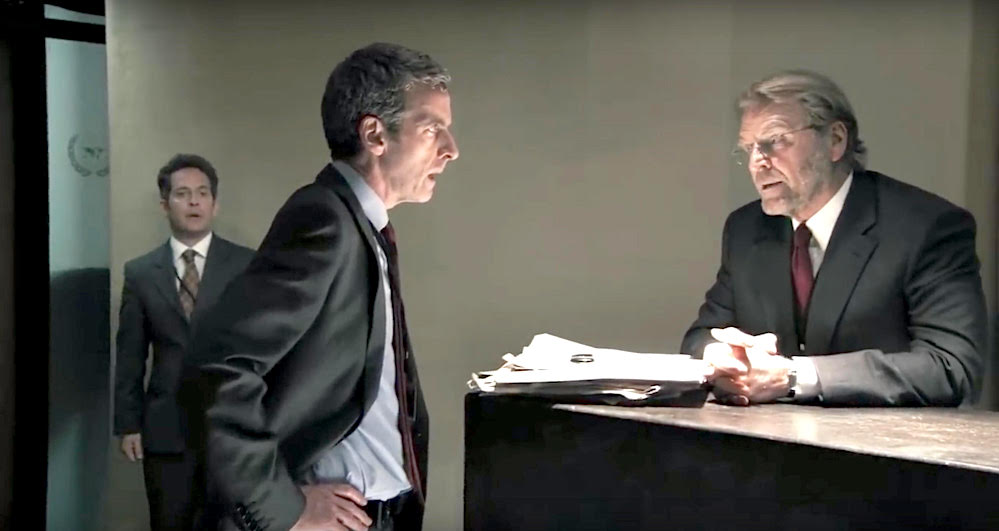

There is a moment that hints at deeper layers to Malcolm Tucker during the film’s climax at the United Nations. At a clandestine meeting in the Meditation Room, Tucker is forced to admit that he failed in his attempts to produce the “smoking intel” that would guarantee support for a war that strongly resembles, but isn’t exactly, the Iraq invasion of 2003. The man who until now has only dispensed eviscerations finds himself on the receiving end of a savage dressing down from David Rasche’s Rumsfeld-esque Assistant Secretary of Defense. It’s telling that when Rasche’s character really wants to wound Tucker he suggests that he would be better suited to a life of manual labor, which is to say a real person who feels the effects of political decisions instead of creating them.

For the first and only time Tucker appears vulnerable. He doles out a few baroque threats of bodily harm to the hapless aide who accidentally witnessed the scene, but they ring hollow. The camera lingers on a tight close up of Tucker alone in the room for a long moment. The political shark who will die if he stops bending the world to his will, stands silent and still and exhausted. This rare pause invites the viewer to ask what is going on under the surface. What can possibly motivate this relentless man? Could he possibly find some deeply buried principles in this low moment?

No. Of course not, the film immediately answers. Tucker emerges a moment later as the same political Terminator, only perhaps a newly upgraded model. He no longer just spins the truth, he fabricates it whole cloth, editing an anti-war study into pro-war fiction that seals the vote in favor of invasion.

All of Iannucci’s satires, from In the Loop to HBO’s Veep to last year’s pitch-black Death of Stalin, are fought on the battlefield of language. The most fearsome warriors like Tucker have the knack for verbal agility, while on the opposite end of the spectrum are poor saps like Cabinet Minister Simon Foster, played by Tom Hollander as a man whose is such a trembling blob of equivocation his public statements make him a hero to both sides of the war debate, at one point spawning a pro-war bumper sticker while groping for an innocuous anti-war soundbite. (“Climb the mountain of conflict? You sounded like a fucking Nazi Julie Andrews!”) Iannucci’s trademark colorful vulgarity isn’t there merely to make a glib point like “politics is a dirty business” or “spin is out of control”. It’s the deeper, darker idea that language is everything because objective reality no longer exists. The person who makes it up best wins.

When In the Loop was released immediately following the Bush administration I thought it was the definitive satire of the era. Re-watching it a decade later it feels timeless. The screenplay features a news media eager to treat fluff scandals with equal importance to a war, an ineffectual anti-war movement that gets clobbered because it’s busy trying to win the argument on merit while the hawks simply manufacture the “facts” they need, and throughout the English language is repeatedly dragged out into the public square and tortured.

I mean, I wish I could say it felt dated.