By Glenn Dunks

For a film about teenagers living rough, squatting in dilapidated and abandoned hotels or homeless on the streets, there is a remarkable amount of poetic beauty in Streetwise. The work of director Martin Bell (American Heart) was born out of a Life exposé called “Streets of the Lost” by his photographer wife (also noted as a film still photographer) Mary Ellen Mark and journalist Cheryl McCall and it is the latter pair’s continued relationship with the runaway teenagers who populate its intimate yet sprawling narrative that was so essential to Bell being given the remarkable access that Streetwise offers.

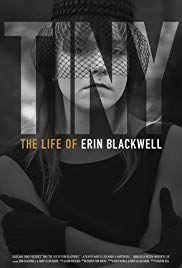

Originally released in 1984 and now restored for its 35th anniversary, Bell’s documentary was nominated for an Academy Award. And it probably would have won, too, had it not been for The Times of Harvey Milk. So not quite as egregious of a loss as I had assumed as I sat stunned through the end credits of the 35th anniversary restoration. Re-released in tandem with a belated sequel, Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell that is also directed by Bell, the power of Streetwise remains with its all too relevant story of teenagers on the streets of Seattle known at the time as the most liveable city in the world...

The most notable of a spate of similarly-themed films released at the time – Leigh Tilson and Rob Scott’s Street Kids in 1983, Peg Campbell’s short of the same name in ’85 – Bell’s film observes the scavengers, prostitutes and drug dealers both up close and from a distance as they get in the cars of clients. Through the camera, Bell captures the juxtaposition between the beautiful Seattle and the grimy street life that his subjects live every day. They put on a brave face, finding community in the absence of family, but through their conversations a predictable story emerges to explain how they all ended up where they did.

After the jagged beauty of Streetwise, I was initially taken aback by Tiny, which picks up the story of its predecessor’s most memorable face, Erin Blackwell, now in her 40s with ten kids and living in a house in the Seattle suburb of Kirkland. Her slender teenage frame now ravaged by a life of various addictions and methadone, not to mention the hopes and dreams for herself and her children that will never come to pass. I was at first disappointed that Tiny had lost the textural aesthetic of Streetwise, its rich colours and photographic compositions replaced by harsh digital photography (it was filmed six years ago, which goes some way to explaining that). I was worried that this sequel – perhaps more accurately described as a companion piece –was going to suffer in comparison to its predecessor’s mammoth reputation.

What surprised me then about Tiny was not just how different it is structurally and aesthetically, but in fact how deeply I found the movie affecting me. So overcome by the weight of continuing Erin Blackwell’s story on the heels of watching Streetwise was I that I became overwhelmed by sadness. I in fact had to turn it off some 45 minutes in and put on old laugh-track sitcoms just to remove myself from its gnawing presence, returning to it the next night. It shook me in a way that surprised me.

Erin (“Tiny” was her nickname) is open about her past with the children that are old enough to understand it as well as with a man, Will, a father to five of Erin’s children and a father figure to the rest. His appearance in her life signalled something of a turn for the better, but which Erin suspects can only leads to more heartache and pain. She offers her children a home, which is more than her own mother was able to do (having appeared in Streetwise, she returns here although not entirely aware of the damage her neglect caused three decades ago), but the cycles of oppression and abuse rear their heads and even as Erin tries to do her best, holding on to those cherished dreams, it is clear that there are just some things that will remain with her to the grave.

Clips from Streetwise, including previously unseen outtakes, dot the narrative of Tiny. We see the then 14-year-old Erin get her hair done into that memorable Joan Jett rocker chick ‘do, and we see her more personal interactions with the Streetwise crew that we weren’t privy to in the earlier film due to its sprawling cast of subjects. Also featured is footage from the early 2000s from what I assume is another previously made yet unreleased sequel that also followed Erin after her time on the streets.

As a work of cinema, of light and sound and all that we associate with that, Tiny does pale in comparison. It's a rougher film, scrappier even. But when placed side by side, is creates a damning portrait of the American class struggle. One crippled by pain, both physical and emotional, that is haunted by the lost potential of millions who, like Erin, never really had a chance.

Release: The pair are playing the Metrograph. Janus Films will hopefully release them on home entertainment soon. Is it too much to ask that a Streetwise get the Criterion treatment? It deserves it and, let’s be honest, is far better than a lot of movies on that label.