By Glenn Dunks

There is a moment towards the start of The Edge of Democracy where director Petra Costa suggests that she thought both she and the political democracy of her homeland, Brazil, “would be standing on solid ground” now that both are in their 30s. It’s a noble idea not to mention a bit cute and certainly a little naïve because anybody with the benefit of hindsight knows that one’s youthful ideals often rarely bear such fruit.

There is a moment towards the start of The Edge of Democracy where director Petra Costa suggests that she thought both she and the political democracy of her homeland, Brazil, “would be standing on solid ground” now that both are in their 30s. It’s a noble idea not to mention a bit cute and certainly a little naïve because anybody with the benefit of hindsight knows that one’s youthful ideals often rarely bear such fruit.

It’s also an appropriate introduction to this, her third feature. That blending of the two narratives is just one small part in how Costa, whose 2012 earlier feature Elena was an even more intimate debut, makes her homeland’s troubling descent into authoritarianism all the more painful. It’s personal. For her and the audience of her gripping and devastatingly relevant documentary.

The Edge of Democracy is easily one of the great works of documentary this year. It is a riveting experience; an impeccably edited navigation of Brazil’s volatile relationship with democracy in the shadow of a deadly military regime that Costa’s own parents fought against in exile and which ended not long after she was born. An urgently essential work that is sadly too late of a warning shot for some, and perhaps just in time for others. It’s a film seething with anger and sadness – or is that hopelessness? – that nonetheless pulsates with blistering cinematic power.

But for as many head-spinning facts as the film flings at its audience about former President Lula and the then-President Rousseff and the many allegiances, backroom handshakes and shady business deals that is common for Brazilian politics no matter the party, Costa herself is never completely blind to the ambiguities of these turbulent years. Yes, it appears quite clearly that the right-wing factions of Brazilian politics (not so coincidentally all older, white men) are conjuring fear in their society in order to poison voters against the progressive leaning Worker’s Party to protect their wealth and disguise their own corrupt immorality. But, as Costa notes, there are inconsistencies that don’t completely absolve Lula and Rousseff.

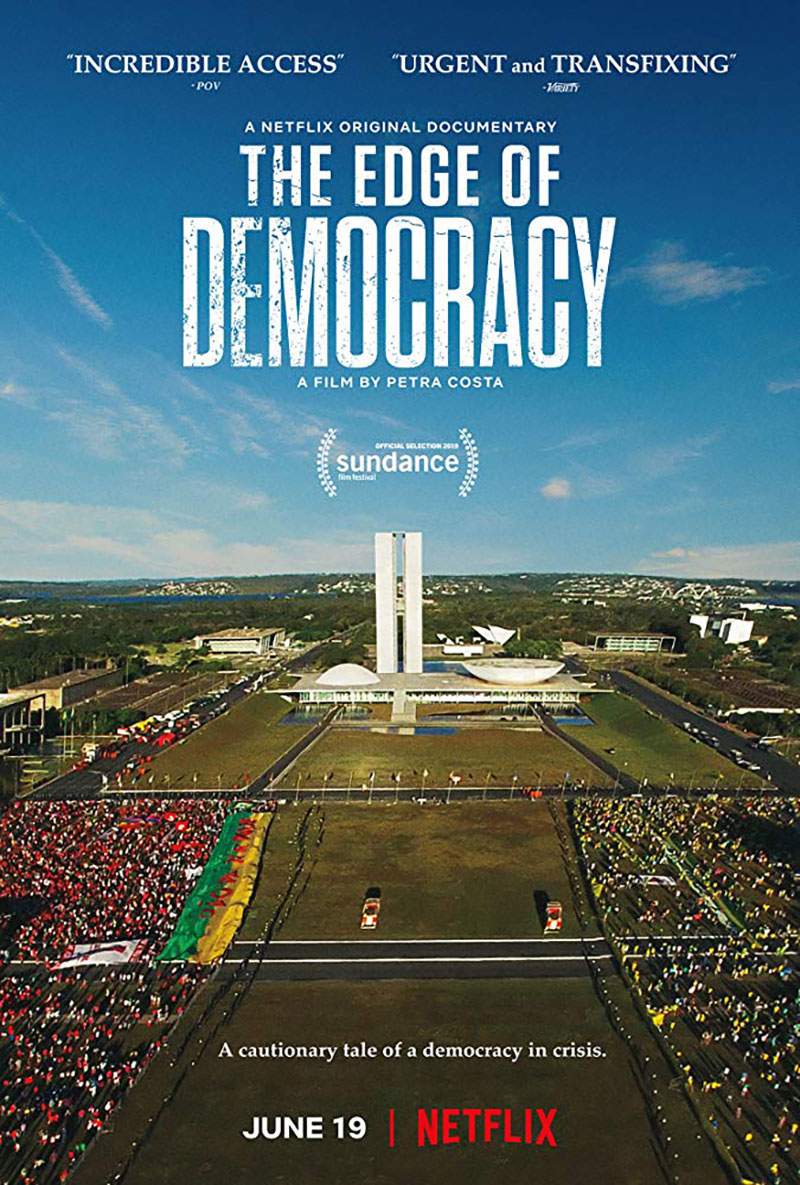

The Edge of Democracy is a story of several decades told with alarming immediacy. No less than 15 editors are credited, which seems crazy but also makes total sense considering the digest of archival footage and more contemporary protests and political clashes that makes the two-hour runtime feel positively brief. These moments buzz with the same sort of chaotic electricity that fused throughout the likes of Jehane Noujaim’s The Square or Evgeny Afineevsky’s Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom (coincidentally both Oscar nominees). Their work is heighted by the music of four composers and João Atala’s graceful cinematography, particularly across recurring sequences that silently slink throughout the Presidential palace as well as masterful use of drone photography that acts as a metaphor for the rich and powerful, hovering above the citizens they supposedly work for, god-like and yet all too willing to sell them short.

It is a film of some delicious visual ironies too. A lengthy sequence – well, it feels lengthy compared to the frenetic protest sequences and political thriller pace of the rest of it – in which a man attempts to write the words of the Brazilian flag “Ordem e Progresso” (Order and Progress) only highlights the distinct lack of those two very things among the narrative, while another involving a literal wall set up to divide people on opposing sides during the Impeachment vote feels remarkably pointed both thematically and in how shabbily it is assembled. So while Democracy may lack the structural quirks and stylistic leaps that some expect in more contemporary documentaries, it never skimps on its own aesthetic choices.

Costa ends the movie with a question about starting anew and yet for both her country and many others, one has to wonder how many times this can be achieved before we realise it is humanity’s nature to go against our better interests and blindly follow the capitalistic, patriarchal systems that routinely cause such societal breakdowns. If people haven’t figured it out by now, then when will they ever? The parallels particularly to American and Russian politics are of course right on through the end credits that inform us the lawyer and judge who helped bring down Lula was then given his own role in the new government of his conservative rival. Same script, different cast.

There is another quote that sticks out, but this one isn't by Costa, but by Warren Buffet. And it's one that sums up the film, and seemingly the whole world right now, perfectly. "There's class warfare, all right, but it's my class, the rich class, that is making the war. And we're winning."

Release: Streaming on Netflix worldwide.

Oscar chances: It's not just a solid contender for the nomination, but it's a frontrunner for the win.