Scene: Immortality

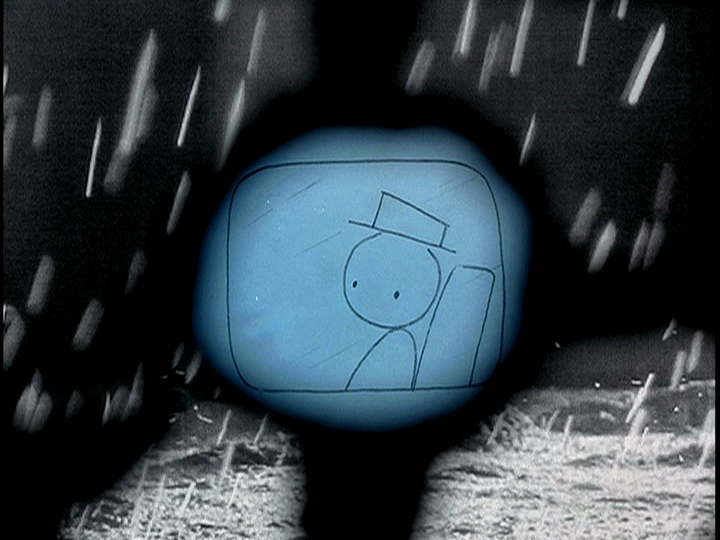

Bill, the protagonist of Don Hertzfeldt’s animated masterpiece It’s Such a Beautiful Day (2012), is the picture of ordinariness. With only his simple rectangle and line hat to distinguish him, he is every man.

The sweeping classical music on the soundtrack as we are plunged into Bill’s existence briefly tricks us into thinking that Bill's life might be an extraordinary one. The film shares some selections with The Tree of Life, released the year before. But where Terrence Malick matched that music to images of equal grandeur, like the creation of the universe and butterflies landing on Jessica Chastain, Hertzfeldt goes in the opposite direction, using symphonies to elevate depictions of the most insignificant events conceivable. Bill’s life is as humdrum as his appearance...

Most of the incidents we witness wouldn’t earn the leap from short term memory to long term. Like when Bill decides to make toast and changes his mind, or when Bill recognizes an acquaintance on the street but neither can muster a comment. Hertzfeldt seems to be saying that the thing we think of as memory is just a highlights reel. This stuff, the day to day nothing that we forget as it’s happening, that is the bulk of life. And it’s washing away Bill’s sanity on a rising tide of tedium.

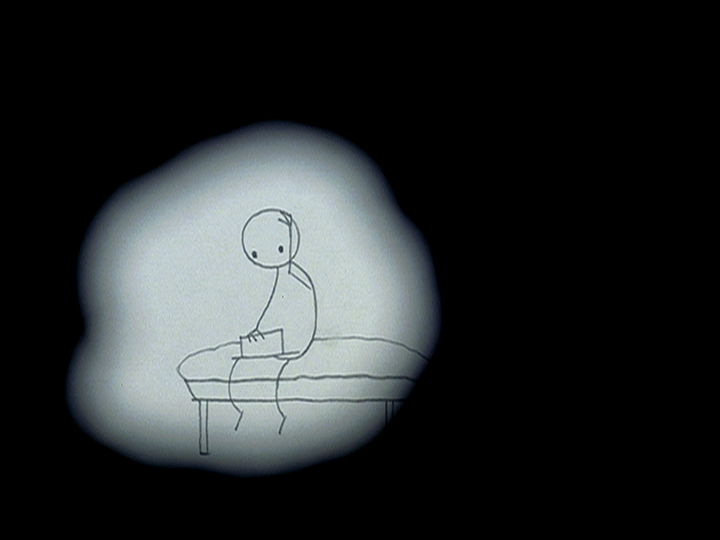

Early in the film, Bill receives an ominous if vague diagnosis that seems to indicate rapid physical and mental deterioration. In a moment of astonishing animation, Bill sits on his hospital bed and absorbs this information, removing his hat and rubbing his hand over his head. It’s the kind of acting that would win accolades were it not accomplished with a pencil. After this seeming death sentence the minutiae of everyday details begin to amplify and overwhelm Bill’s senses. Hertzfeldt cranks up the style until mundane details reach hallucinatory levels. Everything is simultaneously beautiful and horrible. The film is so fluid, occasionally crossing into complete abstraction, that it's tough to separate cause and effect. Is Bill’s closeness to death heightening his awareness of the details he was ignoring? Or is the grinding monotony of life causing him to become unglued?

It’s Such a Beautiful Day was originally released over the course of six years as three separate short films, each around twenty minutes, before being sewn together into a single feature. It sounds like it should be an awkward fit but it's enormously effective. The three segment structure mirrors the refractions of Bill’s twisting kaleidoscope of existential anxiety. The first two segments bringing him to the brink of transcendence with the last unexpectedly crashing through.

At the end of the first segment, Bill appears to be at death's door only to abruptly pull back in a way that manages to feel more like a let down than a miracle. He ends this segment ready to re-enter his daily routine, sitting on a bus staring at rain puddles in a shot I find intensely moving. In the second segment the film pulls back to place Bill’s predicament in the context of the whole human race, tracing his bloodline in wonderfully bizarre detail back to his ancestors who all suffered similar mental illness (a forbearer of Bill’s once “strangled a rock in a fit of religious excitement”) As Bill appears to arrive, finally, at his end, the last segment builds to a thrilling crescendo only to veer suddenly at the last moment and grant a reprieve.

The film, on a whim, grants Bill not just a temporary pardon from an early death but a release from mortality for good and all. Bill will not just survive this illness, the narrator informs us, he will never die. And live on he does, doing what we would all hope to do without a time limit. He learns everything and goes everywhere. He lives on to meet the alien race that next inhabits the planet. The film closes on an eternal Bill, floating through space, passively watching as the stars blink out their lights one at a time.

It's a sublimely rendered scene but it also makes a mockery of humanity's foolish desire for more time. Without the finality of death Bill has lost his humanity, and an infinity of wonders has become less meaningful than the procession of trivial details that began the film. Why pine for immortality when the vast majority of the life you do have is slipping by unnoticed? Who needs to go searching for awe in eternity when there is wonder enough in watching the lights of traffic at night as you fall asleep in the backseat of a car?

Previously on The New Classics