By Glenn Dunks

Because not everybody can be in Toronto or Venice, there are still plenty of great movies to watch!

American Factory is a film that hovers over the precipice of tragedy for its entire runtime. Its subjects exist in a state of perpetual uncertainty, never sure about whether they have a future or if the rug is going to be pulled out from under them yet - again. They are all workers from the Moraine Assembly Plant, once owned by General Motors, in Dayton, Ohio, that closed down during the recession, but which has since been purchased by Chinese company Fuyao to begin operation producing glass for (cars that America no longer seems to make).

American Factory is a film that hovers over the precipice of tragedy for its entire runtime. Its subjects exist in a state of perpetual uncertainty, never sure about whether they have a future or if the rug is going to be pulled out from under them yet - again. They are all workers from the Moraine Assembly Plant, once owned by General Motors, in Dayton, Ohio, that closed down during the recession, but which has since been purchased by Chinese company Fuyao to begin operation producing glass for (cars that America no longer seems to make).

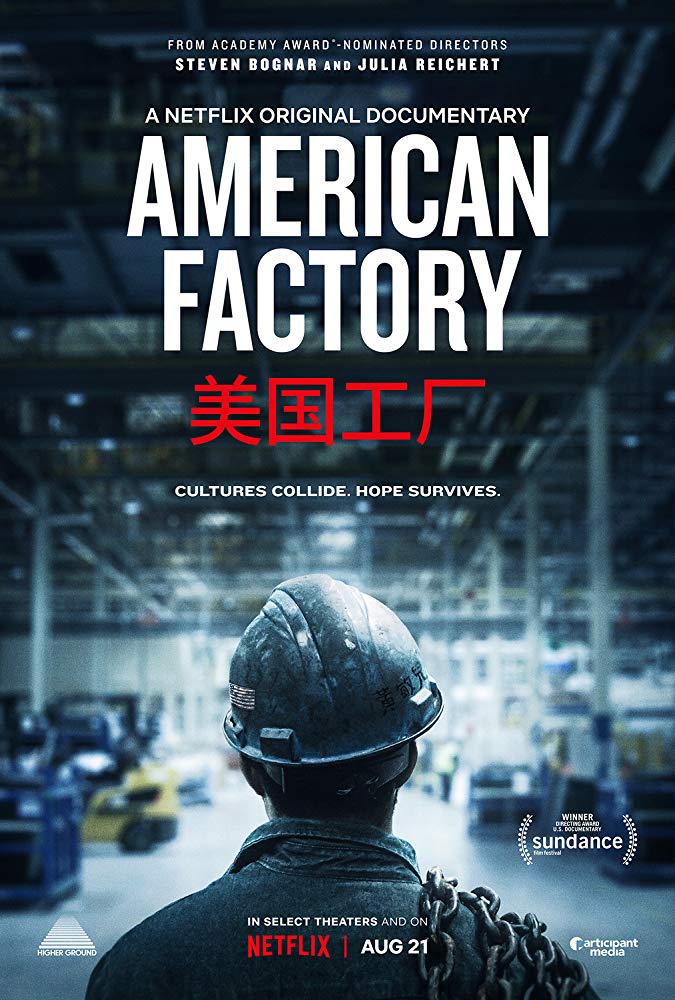

Directors Steve Bognar and Julie Reichert return to the location of their Oscar-nominated short documentary The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant. That film, which charted the factory’s production of its final automobile, filmed its subjects predominantly from inside cars as they arrive at work or in bars as they mulled over their futures. American Factory, then, is a major step up from a production stand-point, but offers just as humane a portrait of people struggling to find their place in a changing world. A world that is rapidly moving away from the old ideas of the “American Dream”.

Bognar and Reichert are Dayton locals and have been directing and producers partners since 2006’s Emmy-winning A Lion in the House (Reichert has been Oscar-nominated twice more in 1978 and 1984). That insider sense is imperative to the success of American Factory, which is a truly special film. A challenging re-evaluation of American ideals and, if you choose to look at it that way, an interesting take on the Trumpian concept of “Make American Great Again”. It’s a movie that appears desperate to be a feelgood tale of hard-working Americans being rejuvenated by the promise of a new day with plentiful work and a future that they can count on, but which consistently comes face to face with the realities of the global, capitalist economy.

Initially heralded as the saviour of Dayton – some 2000 jobs are promised, although the plant once provided work for 6000 at its peak during America’s boomer period – Fuyao’s expansion into America is greeted by a mixture of relief, scepticism, happiness and dissatisfied. The filmmakers gained remarkable access to Fuyao’s chairman Cao Dewang and the audience is granted a rare front-row seat to the potential future of the global workforce whose expansion into America is threatened by a workforce inexperienced in both glass-making and Chinese work ethic, the language barrier between the American employees and the Chinese workers they have shipped to America to teach the Ohioans, and most importantly by a rising tide of unionisation among their new American workers who grow increasingly cognizant of the lower wages and tougher working conditions.

It is this latter section that is American Factory’s most dramatic. In the shadow of Barbara Koppel’s Harlan County, USA and the Sally Field vehicle Norma Rae, American Factory’s most potent strand shows workers like Jill Lamantia, a forklift driver who is driven deeper into the efforts for workers to unionise. This is despite Cao Dewang’s insistence that bringing the union into the plant will result in pulling out of America altogether and once again leaving the people of Dayton, Ohio, without a significant source of employment. The film left me genuinely curious about what a modern labor force looks like when two cultures are so awkwardly smashed together. I don’t know if this factory is the best example of that, but it’s something that many more will no doubt soon be forced to confront.

Despite having Barack and Michelle Obama listed as producers (after the fact, mind you), American Factory is decidely apolitical. Illusions are made to the current President in a visit by a Democratic politician urging the workers to unionise, but the political leanings of its subjects are left unexamined. Likewise, their feelings about working for a Chinese company – although many testify to the fondness they feel for their international colleagues. If anything, the film is perhaps too naïve towards the situations that got the people of Ohio into this mess in the first place (Closing of a GM Plant also chose to focus on the plant and its people instead of the financial crisis brought on by the sort of people who are currently in high profile Washington D.C. positions and/or enjoying the high-life).

Despite reaching its own sort of narrative climax, American Factory ends once again on a note of uncertainty. History isn’t necessarily repeating itself in Dayton, but probably will inevitably reach the same end point that we saw in The Last Truck of people who have devoted their lives to factory work being left out in the (figurative and literal) cold. It sides with the workers (both American and Chinese), while acknowledging the world within which they operate. And even though it stays relatively safe politically, it finds a very specific kind of compassion. Tragedy may be on the horizon, but so too may something better.

Release: Streaming globally on Netflix.

Oscar chances: Oh, definitely. In fact, I would personally suggest the race is between this and One Child Nation. This actually probably has the edge due to the Netflix factor (they have one a short and a feature documentary prize) and the Obamas give it a great hook. Just the name alone will mean people watch it and the doc branch may want to steer people towards recognizing three-time nominee Reichert.