In this new series, members of Team Film Experience watch and share their reactions to classic films they’ve never seen.

by Lynn Lee

The 1970s may have been a great era for cinema, but they were a pretty lousy time for faith in the great American experiment. Between the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers, the Church Committee reports, and of course Watergate, there were seemingly endless reasons to suspect the U.S. government and other institutions meant to serve and protect the public were instead covering up all manner of malfeasance—and that they might be watching you if they thought you were a threat. This generalized paranoia found fertile ground in Hollywood, leading to a spate of conspiracy thrillers of varying quality and goofiness.

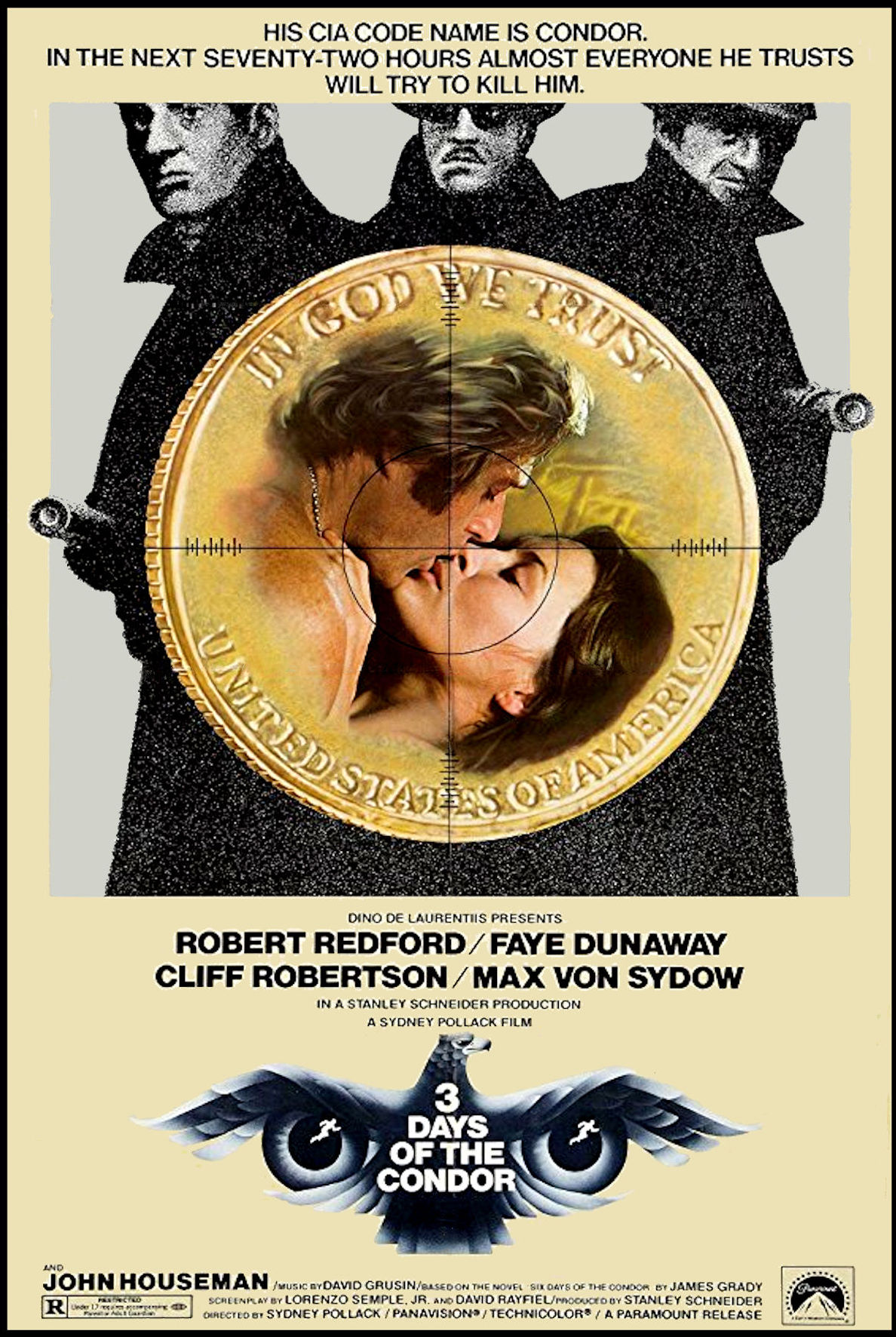

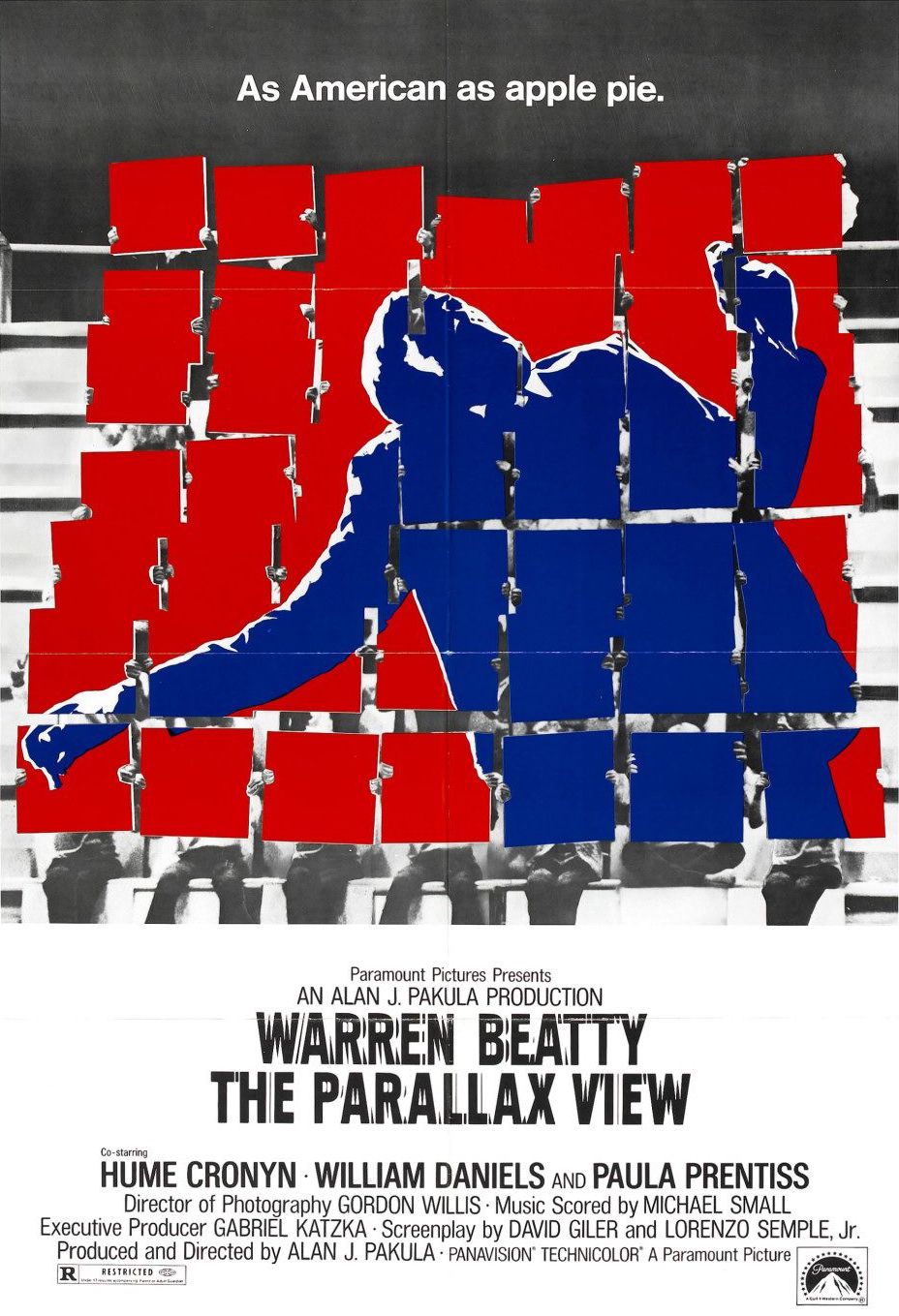

Until last month, the only one of these films I’d seen was All the President’s Men (unless you count Chinatown and Network, which I’d argue you could). But something about the social and political tensions of today made these movies seem especially current again. So it seemed like a good occasion to watch two of the most famous examples of the genre: Three Days of the Condor (1975) and The Parallax View (1974)...

Seeing them back-to-back was both clarifying and fascinating, and not just because of the “holy ’70s” stylings. Besides finally firmly establishing in my mind that Condor was the one directed by Sydney Pollack with Robert Redford and Parallax the one directed by Alan Pakula with Warren Beatty, it also revealed how indebted they were to earlier films (Hitchcock’s “innocent man on the run” thrillers in particular; also The Manchurian Candidate for Parallax) and how much they influenced later ones, from Arlington Road to Captain America: Winter Soldier. In that sense, they’re at once products of their time and of all times. Yet despite their thematic similarities, I was equally struck by their differences in construction and approach.

[Warning: SPOILERS]

THE HERO

Condor: Redford stars as Joe Turner, a CIA analyst in NYC tasked with scouring books of all kinds for plots or codes that might coincide with actual CIA operations. He comes back to the office one day from a lunch run to find all his co-workers have been slaughtered. For a bookworm, Joe demonstrates impressive field agent skills – running, evading, fighting and outwitting his adversaries as he searches frantically for the truth. He’s also rough on women (see below), but ultimately emerges as a beacon of truth in an increasingly cloudy and tarnished moral universe. And because it’s Redford (then only 39, and bearing a startling resemblance to Brad Pitt), you root for him to continue surviving against all odds.

Parallax: Beatty plays Joe Frady, a second-string Seattle journalist who witnesses a political assassination that he only begins investigating when he discovers that all of the other witnesses appear to be getting offed. Like Turner, Frady proves quick on his feet and unexpectedly adept at getting out of tight spots; unlike Turner, who always seems to stay one step ahead of the big bad, Frady always seems one step behind. Indeed, as the movie goes on, I was left wondering whether the big bad was just stringing him along for their own purposes. Turns out they were.

THE GIRL

Condor: Joe Turner’s Chinese American co-worker and apparent love interest (Tina Chen) makes a striking but short first impression as she’s taken out with the rest of their colleagues. So the main female role goes to Faye Dunaway, who makes the most of a pretty problematic role: an unwitting stranger whom Joe Turner basically terrorizes and imprisons so he can use her place as a safe house. Conveniently (he does, after all, look like Robert Redford), she ends up falling for him and helping him of her own accord. But not before getting some good zingers in about their uneven power dynamic (“Have I raped you?” “The night is young.”).

Parallax: Paula Prentiss gets only a couple of scenes near the beginning as Joe Frady’s ex, a fellow journalist who first alerts him to the fact that someone may be coming after them. Although she exits the movie almost immediately thereafter, it’s arguably guilt over not taking her Cassandra-like warnings seriously that drives Frady to investigate. Our last glimpses of her are haunting – through an opaque glass door, and then on a morgue slab. It’s an open question whether this is a better or worse use of a female character than Dunaway’s in Condor; I’m giving the slight advantage to Dunaway, but really neither movie does itself any favors in the female character department.

THE ADVERSARY

Condor: It becomes apparent early on the rot is somewhere within the CIA; the only question is how deep and how high up does it go? We’re kept guessing till fairly late in the movie, even as we see periodic glimpses of urgent confabs at CIA headquarters, yet the truth ends up feeling surprisingly small and anti-climactic—a feeble excuse for such horrific crimes. While the CIA may come across as an organization that doesn’t quite seem to have its shit together, it does have a formidable ace in the form of its hired assassin Joubert. Max von Sydow owns this role, shifting seamlessly from wordless menace to unexpectedly urbane, slightly world-weary charm when he does finally get to speak at length. Fittingly, however, the last spoken words in the movie come from an agency mid-level (Cliff Robertson) who’s not unsympathetic to Joe but also unwilling to call out the corruption in their ranks.

Parallax: Frady’s investigation leads to the Parallax Corporation, which appears to be in the business of arranging assassinations, though it’s never explained what their cover business is, who (if anyone) is hiring them, or how they select their targets. The film also suggests the government, represented by a congressional committee appointed to investigate the assassination, is complicit in covering up Parallax’s actions. This makes Parallax at once a creepier villain than the CIA, but also a more amorphous one that seems based not so much in reality as in our most Kafka-esque nightmares. That quality is most memorably embodied in a hypnotic “test” scene in which Frady is bombarded with a six-minute sequence of images and words that are repeated in different and increasingly disturbing configurations, bringing to mind the brainwashing scenes in The Manchurian Candidate and A Clockwork Orange. The filming and use of shadows in that scene, along with the long shots of their building exterior (the former L.A. Superior courthouse, I believe) with its mirrored glass surface and undulating outdoor plaza, make the whole enterprise feel like something out of a David Lynch movie.

THE CONSPIRACY: HOW PARANOID DOES IT MAKE YOU?

THE CONSPIRACY: HOW PARANOID DOES IT MAKE YOU?

Condor: Of the two films, Condor is the more tightly paced and cohesively plotted. While the motives behind both the crimes and the cover-up may seem improbable, they’re also comprehensible and just within the realm of moviegoer suspension of disbelief. Joe Turner’s last act of defiance may be futile, but there’s still a glimmer of hope that the truth he’s uncovered will be published and will protect him. It’s the same hope we hold on to in real life, faith in the courage of whistleblowers and the free press.

Parallax: Pakula’s film is by far the bleaker of the two, with its would-be whistleblower set up as the fall guy. It’s also far weirder and at times surreal, between the “brainwashing” sequence and other, tonally bizarre scenes in which Frady pursues his investigation—including a bar encounter in which he gets semi-propositioned with an off-color joke about breasts and provokes a no-holds-barred barroom brawl; an uneasy encounter with a lab scientist, his chimpanzee, and his even more ape-like human subject; and a rehearsal for a campaign rally, complete with an out-of-sync tuba player, that seems to be taking place in a giant school auditorium so cavernous it requires the candidate to be driven to the stage in a golf cart. None of these leads ultimately yield a coherent explanation of what’s going on, but that may just be the point: we were never meant to find out. The grim punchline arrives courtesy of that nameless, almost faceless congressional committee (again filmed in deep Lynchian shadow), repeating its canned findings that the assassin “acted entirely alone” and that the committee found “no evidence of any wider conspiracy…no evidence whatsoever.”

Which one did I find more effective? Three Days of the Condor is the better thriller, in that it actually identifies and exposes a concrete conspiracy. The Parallax View, by contrast, resists any such neat cabining, because it’s meant to unmoor any false assurance that the individual can ultimately get at the truth or prevail over this elusive, all-powerful entity that seems to be pulling all the strings. Put another way, I found Condor to be the more satisfying of the two, and Parallax the more unsettling. Both have their place in the conspiracy thriller world, but I suspect the imagery from Parallax will linger with me longer.

If you've seen either of these how unsettled / satisfied were you?