Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher are back on Oscar's radar. Sorkin's sophomore directorial effort, Trial of the Chicago 7, is set to premiere on Netflix later this week while Fincher's movie about the making of Citizen Kane, Mank, is scheduled for a December release, also on Netflix. Looking back at the last time both these men were in the awards conversation brings us to 2010 when The Social Network was the critics' favorite going into Oscar night. The drama about the creation of Facebook was the David that fought against the Goliath of Weinstein's The Kings Speech. Unlike the biblical tale, however, the giant won this battle.

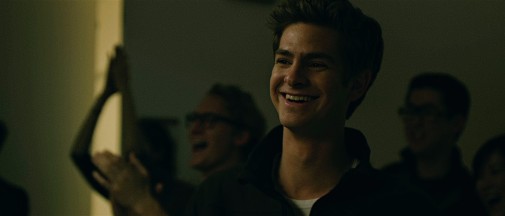

The signs of trouble and pending defeat were obvious for most pundits. After all, despite the film getting eight nominations, one of its stand-out performers and expected honorees failed to make the cut. Andrew Garfield had earned great support from the precursors and reviews to match, making his absence from the Best Supporting Actor lineup a shocking snub…

The Social Network is one of those mechanically perfect films in which every ingenious element works like clockwork or perhaps the insides of a gun that never misfires. One can argue about its morality and the ideological complexity of its arguments, but there's a precision to the construction that's as undeniable as the rising sun. Clothed in a robe of electronic melancholy courtesy of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, this historical piece looks at the start of Facebook, though its perspective on the story is far from a glamourizing creation myth.

American cinema is full of inspirational "true" stories about self-made men, morality plays infused with a capitalistic devotion to those who succeed and become rich, shaping the world in their image. Sorkin's screenplay starts peeling the varnish off the mythos, but it's Fincher's assured direction that seals the deal. Mark Zuckerberg may be portrayed as a genius, but he's also a verminous traitor, ready to sell out his best friend in name of capital and prestige, a petty man, a disgusting chauvinist and social climber with no concern for ethics in whatever shape or form.

Jesse Eisenberg's Oscar-nominated performance underlines this undercurrent of malice, often sulking in the background and managing to deliver pages upon pages of rapid-fire dialogue without ever moving his upper facial muscles. It's a purposefully robotic performance that's further alienized by Jeff Cronenweth's cinematography. Notice how his eyes are regularly obscured by shadow, no catchlight reflecting in their dark pools. It's a fairly common trick to build an unconscious barrier between the audience and the character, but just because it's common doesn't mean it's any less effective.

I mention all this about Mark Zuckerberg's portrayal because, in essence, more than playing the real person that is Eduardo Saverin, Andrew Garfield's embodying a performative counterpoint to his costar. While The Social Network structures itself around two lawsuits against Zuckerberg, Saverin's, and another made by the Winklevoss twins and Divya Narendra, it's Eduardo's betrayal at the hands of Mark that shapes the tonal and emotional arcs of the movie. Rooney Mara's briefly seen Erica Albright fulfills a similar function, though her acerbic abrasiveness is closer to mirroring Eisenberg rather than complement him with canny contrast.

While Eisenberg's Mark is a monument of stillness, Garfield spends the movie in flurries of nervous movement. Even the simple act of holding a beer bottle can become a mini-performance of fidgety business. That's not to say he's imprecise or sloppy. Such things are next to impossible when one is dealing with a director like Fincher who'll do a hundred takes until he gets what he wants. Rather, it's purposeful disquiet, a needling reminder that there is a world happening at the margins of Mark's perception.

Look out for Garfield's silent reactions and aborted movements throughout the film and you'll find a painful painting of unreciprocated devotion. In any given scene, Eduardo's the only person who reacts according to the dramatic weight of whatever is happening, be it a lawsuit or a social faux-pas that Mark committed without realizing. Everyone else seems incapable of self-awareness, much less self-critique. He's a destabilizing presence, a single drop of sincerity in a sea of arrogant posturing. No wonder that Garfield, with his big Bambi eyes and cracking voice, often comes off like a lamb being readied for the slaughter.

Despite this, don't suppose that Garfield's performance is a procession of nervous ticks and martyred poses in the style of late-career Montgomery Clift. For one, he's delightfully silly and adept at mining Sorkin's garrulous character writing for droll humor. Whether dancing awkwardly to the Caribbean tunes of a miserly Harvard party or scoffing at the pretentiousness of Justin Timberlake's Sean Parker, Garfield finds space for levity in a narrative whose endpoint is a broken spirit and ruined friendship. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Garfield also delineates the steely resentment that as calcified his heart in the "present-day" scenes.

Again, he complements Eisenberg through contradiction. Mark slouches in his chair, a sullen kid who'd rather be alone in his room than discussing important matters inside cold conference rooms. Garfield's Eduardo, however, remains ramrod straight through the scenes, rarely looking or talking directly to Mark unless he wants to punctuate a particularly withering remark. Garfield ages himself without the aid of any cosmetic effect, simply by draining his character of softness and externalized affection.

You sometimes see a glimmer of the youthful petulance, like when the story of the chicken is brought up. Suddenly, he looks his age, if only for a fleeting moment. However, for the most part, the old Eduardo is dead and The Social Network is the forensic investigation by which we, the audience, get to discover how the fatal blow was handed. As the two facets of the performance and its chronology converge, tension grows within the actors' performances and the fabric of the film's dramaturgy. Garfield's final scene is the release of that tension, the moment when the twisted rope gives out and explodes in a firework of busted threads.

We see many signs that Eduardo suspects Mark's essential ruthlessness, but even he is shocked by the ultimate betrayal that's unmasked in Garfield's final scene. The actor who, up until then, had been a bottomless reservoir of vulnerability in this earlier storyline, finally gives in to the mean pettiness that every other character has been indulging in. This is a film where violence usually manifests in witty retorts and backroom dealings, making Eduardo's smashing of Mark's laptop and booming shouts a seismic violation of the norm. He's become like the other monsters, but his anger is righteous and rightful.

It's startling too and Garfield only makes the moment into an even bigger deal as he vomits Sorkin's dialogue with the kind of venom one might have thought beyond Eduardo's repertoire. The actor plays it as a drowning man hellbent on causing as much hurt as he can while his lungs give up the ghost. His fury burns our eyes, and his pain breaks the heart, feckless aggression pouring out of his tense body as lava comes out of an erupting volcano. It's almost primordial in its magnificence, a titan screaming his death rattle for the world to hear while "Hand Covers Bruise" rings in the background, a requiem for a dead man. If that's not an Oscar clip scene, I don't know what is.

Considering the movie's buzz, it's strange that Garfield wasn't able to score a nomination at the Oscars. Internal competition may be partially to blame. Armie Hammer and Justin Timberlake also managed to get good reviews and their fair share of buzz. In the end, Garfield got nominated for the Globe, the BAFTA, and the Critics Choice Award, as well as a veritable mountain of regional critics' awards. As for the Academy, the chosen five were Christian Bale in The Fighter, John Hawkes in Winter's Bone, Jeremy Renner in The Town, Mark Ruffalo in The Kids Are All Right, and Geoffrey Rush in The King's Speech.

As we all know, Bale won and, of those five, Hawkes was the biggest surprise come nomination morning. One thing to point out about this lineup is that three of the men nominated could be argued to be leads instead of supporting players. I'm not saying I consider them as such, but it does underline the big problem of category fraud which makes it harder for truly supporting roles to be recognized. Garfield's part in The Social Network is big, but his narrative prominence and screen time are inferior to those of someone like Rush or Bale. Would you have nominated Garfield in 2010?

The Social Network is available to stream on Netflix. You can also rent it from several services like Amazon, Apple iTunes, and Youtube.