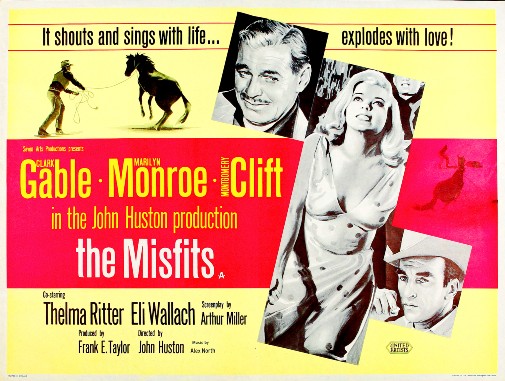

The late-career of Montgomery Clift was laden with tragedy, shaped by the doom that was happening both behind and in front of the camera. While nothing can compare to the cataclysm that was the shooting of Raintree County, The Misfits is another film of Clift that's haunted and haunting. The Angel of Death looms over the picture which unwittingly became the last screen appearances of Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe before their untimely ends. Clift would hold on for a few more years, surviving his co-stars.

However, as legend has it, the movie was showing on TV the night the actor died. His secretary, Lorenzo James, asked the actor if he wanted to watch it to which he answered: "Absolutely not!". Those were the last words he ever spoke to anyone, enshrining the movie in even more cursed memory. It's a pity these morbid curiosities define the legacy of The Misfits. In many regards, it's one of Clift's best and most fascinating pictures…

The Misfits was born of a script written by Marilyn Monroe's then-husband, playwriter Arthur Miller. Supposedly, the man who was then America's most respected dramaturge, composed the screenplay as a valentine for his wife. If indeed it was made with those intentions, it's one hell of a horrid valentine, a grotesque reflection of a marriage on the throes of ruin. Bear in mind that The Misfits is no heartfelt romance despite the kernel of dashed love playing a central role in its narrative.

If anything, the movie's a poem about suffering, death, and the pain that awaits everyone who still holds on to an optimistic worldview. Its happiest passages happen early on when Monroe's Roslyn is getting divorced in Reno. On the day when the matter is settled in court, she's accompanied by the vivacious Isabelle Steers, an older divorcee who's used to help young women in Roslyn's situation. In fact, the melancholic blonde bombshell is her 77th girl.

While out for celebratory drinks, the two women cross paths with a widowed mechanic, Eli Wallach's Guido, and his cowboy pall, a weathered Clark Gable playing Gay Langland. At first, the younger man has his eyes on Roslyn, going so far as to invite the group to his house in the Nevada desert. However, he's quick to give up on any amorous ambitions, seeing as Roslyn and Gay are instantly attracted to each other. For a little while, it seems like this hero of the Old West and fragile damsel will help each other out of their deep despondency. Such naïve hopes don't last long.

In one occasion, when Guido and Isabella return to the desert to visit the couple, Gay brings up the idea of rounding up wild mustangs to sell. Seeing as that endeavor's a three-men job, the group procures another pair of hands to add to their posse. He's Perce Howland, an old friend of Gay who's wasting his life competing in rodeos. Reckless and desperate, on the brink of overwhelming anguish and self-destruction, Perce joins the two other men and fits right in.

The next day, the hungover Gay and Guido, broken Perce and depressed Roslyn venture into the desert in search of the animals. What Monroe's doomed character doesn't know is that they're not after the horses for breeding or riding. They'll sell the horses to dogfood factories. She's horrified by this, by the harsh reality of old-time cowboys taking their wild-willed horses to the slaughterhouse, the majestic creatures turned to mincemeat and the heroes of the Old West made guides to the scaffold.

The western is one of the most knowingly romantic genres in American cinema, but The Misfits is as anti-romantic as they come, twisting the paradigms of film myth into something ugly and bruised, like a rotten fruit whose sweetness has turned acrid. Miller's writing, with all its emphatic symbolisms and well-articulated themes, is heavy-handed to a fault. Thankfully, the execution of this genre evisceration elevates The Misfits. John Huston's direction, in particular, is so dry and harsh it combats the florid bleakness of the text, a chisel that breaks away the common rock hiding a cinematic diamond.

Through his and DP Russel Metty's camera, the Nevada desert is transmuted into a barren landscape that looks as if it's never been kissed by human kindness or known the quality of mercy. Furthermore, Huston was a great director of actors. One would have to be to scrounge up a functioning human drama out of the nightmare that was The Misfits' shooting. Tirelessly documented by behind the scenes photoshoots, the making of this classic was a deep well of misery for all involved.

Huston might have been a gifted auteur, but he spent much time on the shoot drinking into unconsciousness during the day, spending the nights gambling. His actors followed the director's example with Monroe and Clift boozing their lives away and taking pills to make matters worse. As for Gable, the 59-year-old star clashed with his younger colleagues, unable to understand their "Method".

It was perhaps Gable's embittered stubbornness that drove him to insist on doing all his stunts, a taxing exercise that fustigated his sick heart. No wonder he expired less than two weeks after shooting wrapped. There's little evidence pointing towards Thelma Ritter's particular feelings during the shoot but it's probable that she too was miserable. How could she not? It was one of Hollywood history's most famous and most unhappy sets.

The gloom of cast and crew infects the screen, a pestilent disease that makes the hot desert look cold like a dead body already stiffened by rigor mortis. Seeing as The Misfits is a film essentially about suffering, all this off-screen agony was convenient. It lends a layer of caustic authenticity to the cinematic artifice of the project, drawing acidic truth from the madness of the cast member's off-screen lives. In many ways, the movie's as much about dissecting the western genre as it is an autopsy of its actors' stardom.

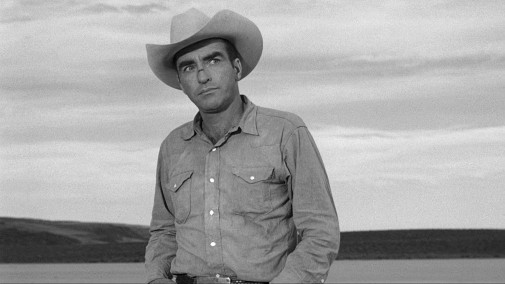

I'd love to wax rhapsodic about Monroe and Gable, both of whom offer audiences what's probably their best performances ever. Nonetheless, we're here to celebrate Clift and celebrate Clift we must. He might not be as extraordinary as his costars, but his supporting turn is quite impressive. The harsh shooting, the psychological games of John Huston, and all of the actor's well-known neurosis bring great weight to his screen presence as Perce Howland.

There's an aura of primordial sadness around Clift, so thick it's almost palpable. Even during the energetic preamble to the rodeo, he looks tired and as if he's on the brink of giving up on living all-together. What's Clift and what`s Perce is hard to parse out, but actor and character are so symbiotically connected one can't complain or say that this is a failure of characterization. The Misfits benefits from such confusion, from this lived-in fucked-up quality by which performer and role become one.

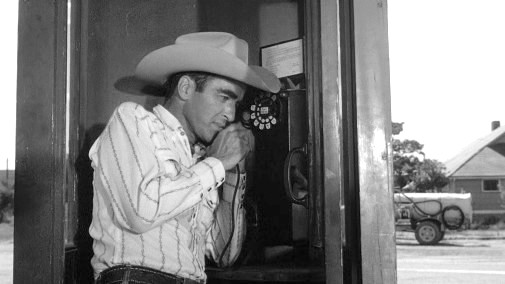

It would be easy to invest too much attention on Clift's appearance and visible exhaustion, but those aspects don't negate the meticulous acting he does throughout. Early on, there's a phone scene when Perce talks to his mother, that vibrates with need. A dialogue turns into a monologue, a confession, a canny self-mutilation of the soul that uses wavering voice and aborted motion as the tools of its horror.

Classifying what Clift does here as naturalism is too simplistic, for he transcends the natural. The mimesis of reality gives way to something more profound, where shattered psychology can find space to express all its sorrows and a look is never just a look, but a silent symphony of longing, of pleading for some joy that never comes. Abrasive and sickening, the performance is a glimmer of glory buried underneath mountains of misery, a ruined orgasm and a perfect fit for Clift at this point in his career. As this rodeo cowboy whose glory days are long gone, Monty is wickedly perfect.

It takes 47 minutes for Clift to enter this 2-hour movie, making for a decidedly supporting turn with not a lot of screen time. It's one of the few times the actor played second-fiddle to other, bigger stars, making for curiosity in his short, though rich, filmography. In 1961, Clift would feature in two projects, both of which would see him take on minor roles. This magnificent American tragedy was the first of the pair, while the second's a post-Holocaust courtroom drama which would earn him his fourth, and final, Oscar nomination. Of course, as you're well aware, that's a story for another time.

Tomorrow: Judgment at Nuremberg