by Daniel Walber

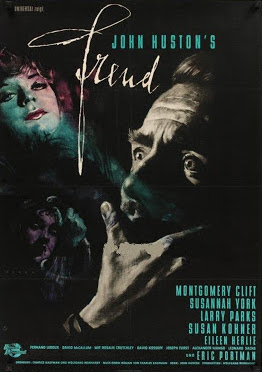

Freud: The Secret Passion (1962) is an odd movie to categorize. It has the moody pessimism of the late ‘60s and the earnest hero-worship of a biopic from the ‘40s. It’s Montgomery Clift’s second-to-last film, but it doesn’t have the “end of an era” energy of its immediate predecessors, The Misfits and Judgment at Nuremberg. In terms of Oscar history, it feels perhaps most significant as Jerry Goldsmith’s first nominated score. And practically no one has seen it.

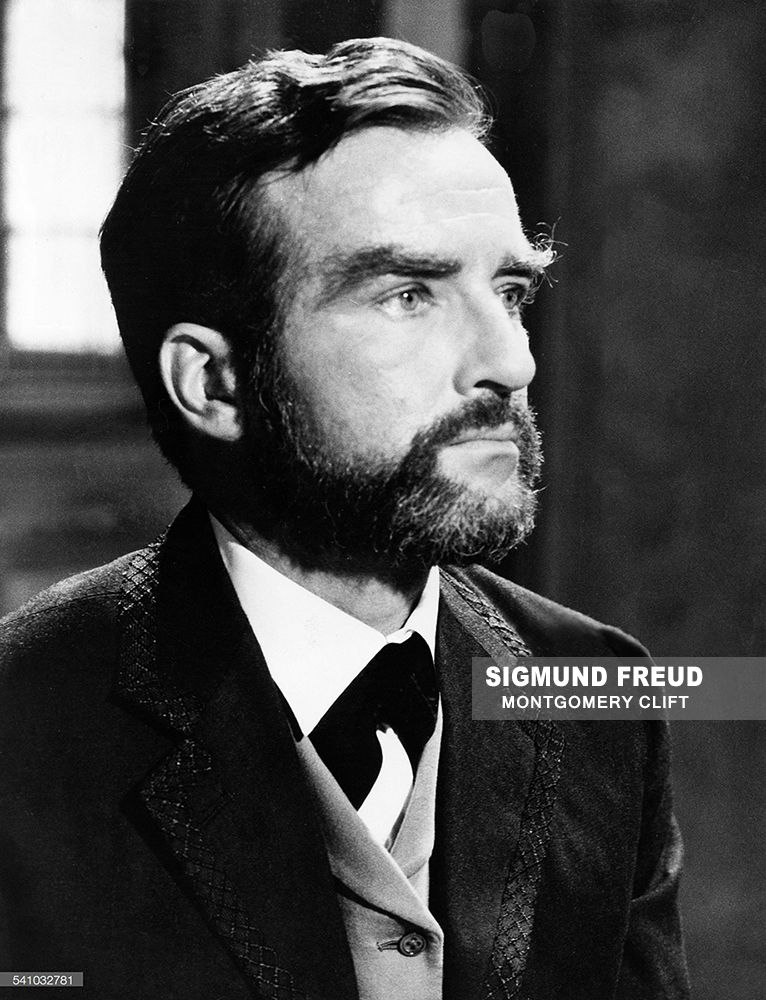

But I’m here to tell you that’s a shame, because Clift was perfect for Freud. I’ve realized this over the course of the past couple of weeks, reading everyone else’s fabulous Monty @ 100 coverage. Freud is, in a sense, the ultimate fusion of two essential parts of Clift’s star persona: the heartthrob and the priest...

Nathaniel talked about this quite a bit in his piece on Red River. Clift was the first of a new wave of male stars, bringing a softer and more fragile masculinity to the screen. This quietly transgressive beauty won him both adoring fans and pigheaded enemies. And so, perhaps as an inevitable corrective, Clift also winds up in the presumed-sexless roles of priest and psychiatrist in I Confess and Suddenly, Last Summer. The tension between his soft sexuality and its rigid opposite makes him the perfect Freud.

It also helps that the movie isn’t really a biography. Freud focuses on just a few years of the doctor’s early career, beginning in 1885. It was adapted from a script by Jean-Paul Sartre, who reportedly quit the project after director John Huston refused to make an 8-hour movie.

The opening narration compares Freud to Copernicus and Darwin, men whose theories remade the world. Yet the film that follows is much less bombastic. Clift plays Freud as curious rather than confident, utterly convinced that the governing explanations are wrong but still searching for an alternative.

He observes, mostly, waiting for something or someone to trigger a revelation. Huston keeps Clift close to the patients, denying any clinical distance and approaching the compositions of Ingmar Bergman.

Freud often feels like a horror film. Part of that is Goldsmith’s score, pushing beyond comfortable tonality. Part of it is the use of darkness and shadow, in both the dream sequences and the over decorated drawing rooms of the Vienna bourgeoisie. But the driving force of anxiety and fear is Clift’s eyes. It is as if Freud perceives his own work as a haunted house, a shock around every corner. His patients haunt him like ghosts.

Freud’s colleagues see “hysteria” and other unexplained phenomena as merely an inconvenience, one caused by the lies of impertinent patients. Freud knows that they’re wrong, the truth continues to elude him. The human mind is “a region almost as black as hell itself,” as the voiceover narration puts it, into which he must tread.

The thing is, he can’t just shine a light into the subconscious by peering at his patients. He also has to turn inward. The more he learns about trauma and its effects, the more he recognizes his suspicions in himself. His own dream sequences become just as important as those of his patients, if not more so.

Every fright inspires him to push further. His eyes open wider and wider, as if dread itself were the engine behind his brilliance. He is terrified that he might, himself, be Oedipus as well. But he is even more afraid of not uncovering an answer. His work is a haunted mirror, from which he cannot turn away.

Eventually he arrives at the revelation that there is sexuality in childhood. “The innocent is born into a world in which it cannot help but lose its innocence,” he explains. It is an assertion that will appall the entire psychiatric establishment, including his most trusted colleagues. But Clift plays it as if their objections barely register, appearing more bored than indignant. After trekking through hell without a map, why would he be afraid of a bunch of stuffed shirts? His fight for recognition seems almost immaterial compared to the actual work of psychiatric spelunking.

It is a revelation tailor-made for Clift, a partial resolution to years of embattled sexuality and contested stardom. The priest and the doctor have just as much sexuality as the heartthrob. They are, after all, the same man. They always have been.

The ending of Freud is almost shockingly bleak, given the hagiography with which it begins. Freud does not win. Nor does Huston hold out his eventual recognition as a happy ending. Knowing more about the world does not necessarily make it a better place to live. Freud’s ideas, like Darwin’s, have spawned their fair share of monsters.

But back to Clift. Has the psychology and sexuality of stardom changed since Freud? The dichotomy between the sexualized and the sexless movie star certainly hasn’t evaporated. If anything it’s become starker, particularly now that Disney seems to own everything. Could an actor like Clift be nearly as famous today? I’m not so sure.

Next: Clift's final film, The Defector (1966)