With the films of Steve McQueen's anthology, Small Axe, earning critical raves as they traverse through the festival circuit, it's a good time to remember some of his previous projects. While 12 Years a Slave was a great success that conquered acclaim and many awards, the rest of the director's filmography has been more polarizing and arguably underrated. It feels wrong, for instance, that his recurring muse, Michael Fassbender, got the first of two Oscar nominations for his least impressive contribution to McQueen's oeuvre. He was much more deserving two years before that best Picture winner, in 2011's Shame...

Shame is a character study about tormented souls, people that aren't bad though they come from bad places. The hero of this woeful tale is Brandon Sullivan, a mid-level executive living in Manhattan whose entire existence is defined by a constant pursuit of sexual gratification. He's an addict, and orgasms are like shots of dope, nothing more. Brandon's past the point where pleasure could overwhelm him or produce euphoria. All that's left is the abatement of pain, the reprieve from the insatiable hunger that threatens to consume him whole, from the inside out.

The sex may come in great quantities, but it's never fulfilling, never enough. Day-to-day existence is hazy, a waking dream of a half-lived life. Brandon floats through the world, insouciant and immaterial, like steam vomited from the underground into the cold Manhattan streets. The desolation of the city at night is Brandon's home, the savannah that he prowls in search of new prey, but it's also the noose that tightens around his neck. One feels he'd welcome the suffocation if only to feel something, anything. Fittingly, the audience of Shame is also made to feel the kiss of asphyxiation, the sorrowful mood smothering.

McQueen's story of addiction and self-hatred is a punishing watch, even if masterfully crafted. Upon its release, there was much controversy about the plentiful nudity and sex scenes, but, like most films with graphic carnality, Shame is profoundly unerotic. It's almost rancid in its avoidance of titillation, making sex look as ugly and unappealing as it's ever looked on screen. The result is a rather sex-negative picture, even if Brandon is such a specific case that drawing generalizations from his pathology feels uniquely wrong.

It's crucial to understand how McQueen's camera captures and molds the performance of Michael Fassbender as Brandon. The nakedness of the actor, for instance, is shot and performed with such casual disaffection, it becomes disturbing. McQueen's compositions, when paired with the minimalistic apartment set, create a sense of clinical observation that rubs off against the sexual body in uncomfortable ways. The framing also doubles down on the punishing alienation that Brandon suffers. He's often pushed to the corners of the image, crushed by large swaths of empty space, unable to be at the center of his own story.

The film thus hinges on Fassbender's shifting expressions and meaningful postures, his silences, and pointed looks. Shame's not so much a showcase as the vivisection of the man in front of the camera. Fassbender's work is the kind of performance that can only exist when there's a lot of trust between actor and director, a willingness to let a character emerge from the symbiosis between performance and form. The early montage, which intersects a sexually-charged subway trip with Brandon's mind-numbing routine, immediately defines the essence of the man and why he's as repulsive as he's scary, both worthy of our pity and our disgust.

In the underground train, Fassbender's face goes from stone-cold provocation to something more carnivorous, dangerous. A sculpture of stern horniness mutates into a shark sniffing blood, a powerful animal chasing its prey through the crowd. It's all in Fassbender's growingly eager eyes and the way the camera movement reflects the energy building up inside the addict looking for a fix. There's also the matter of repeated gesture, of mundanity that's built from a vicious cycle of need.

Brandon's life is designed by patterns of behavior, waves of an addict's desire that crash over him. Any attempt to contradict the tide is useless, as Brandon's body starts betraying his will. First, his tongue slips into words of foul truth. Then it's his genitals that fail to perform. There's no expositive dialogue informing us of this. All the internal savagery of bruised feeling and untreated mental malady blossoms from Fassbender and the camera, two partners dancing in tandem.

Well, it blossoms from that dance as well as the secondary choreographies the actor performs with his scene partners. Despite having a small cast, Shame has one miraculously perfect ensemble. First up, we have James Badge Dale as Brandon's smarmy superior, a figure of cocky machismo that represents the kind of man our protagonist pretends to be. Along with his bespoke suits and tight white t-shirts, Brandon wears a convincing mask of cocky masculinity molded after people like his co-worker. Of course, when compared to Dale's real-deal cockiness, Fassbender's "normal person" façade has cracks that become ever more evident as the film progresses.

The fissures manifest in Brandon's febrile fragility, he who looks as if he's half a step from a panic attack at any given moment. It's in the tension of the body and the non-committal nature of his facial expressions, a faulty machine working on autopilot. In that sense, there's a fascinating challenge to Fassbender's work in Shame. He must play games of seduction and other actions associated with on-screen passion and male confidence but do it with no feeling, just an overwhelming emptiness. By performing it so impeccably, he illuminates Brandon's weakness and how much the man wants to hide that weakness.

If the interactions with James Badge Dale make these dynamics noticeable through direct comparison, his scenes with Nicole Beharie's Marianne illuminate Brandon's inner storm by assuaging it for some precious, fleeting, moments. Fassbender and Beharie have great chemistry, and McQueen makes it all the more evident by staging their date in two long takes. Brandon's mechanic rhythms are disrupted, his hollow charm and gaunt smiles gaining a spark of genuine excitement. He likes Marianne, and she likes him, his nervous awkwardness and odd charm. Walking her to the subway, Brandon allows himself to be weird, he barks and keeps stealing looks at her when she's not paying attention, bursting with an adolescent-like giddiness.

The scene's such a lovely breath of fresh air that we know, from the start, it's all going to end badly. Brandon is always running, running away from himself, from his feelings, from the reality of what he is and what he has become. When someone like Marianne makes him stop running, entices him to be at peace, his tentative control comes tumbling down. Suddenly, this man defined by sex can't get it up, his feelings clogging his virility. Throughout his laborious routine of constant fucking, he might be ashamed of himself, but the shame also turns him on. When there's no reason to be ashamed of sex, he's plunged into another kind of shame, one that's impotent.

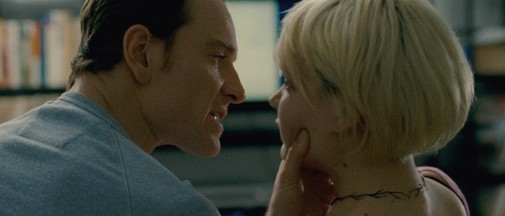

And then there's Carey Mulligan's Sissy. As Brandon's wreck of a sister, Mulligan's an explosion while Fassbender's an implosion. She's also an ugly reflection of the man's true self. The siblings are more similar than they look at first. Superficially, they're near antonyms, but a closer look finds synonymous spirits caught in spirals of self-destruction. Whatever they've lived through in the past has connected them and trapped them, forever bound by the scar tissue of shared trauma. The actors sell the abrasive dynamic of warring siblings while also showing the power they have over each other. For all his bravado and outward aggression, Brandon's afraid of Sissy.

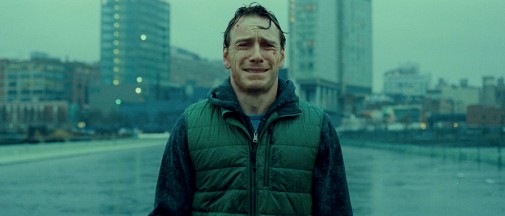

Notice, for example, how he cries while listening to her narcotized version of New York, New York. She's the only one that can affect him so deeply. Later on, during a heated argument, a pause after Sissy says the word sex and suggests she knows how dysfunctional Brandon is, functions like the pin needle that pierces the balloon of his perilous mental stability. After that, he unravels and, like the film's score, Fassbender's performance turns into a crescendo of naked despair. It all builds up to the moment when Brandon allows himself the privilege to feel all the pain he has inside. When he does, it's both glorious and heinous, a supernova of incandescent hurt. It's overwhelming to see, almost stinging.

Awards-wise, Fassbender's tour de force earned him quite a lot of honors. The actor was nominated at the Globes, BAFTAs, Critics Choice Awards, and a great number of critical prizes. He won the Volpi Cup from the Venice Film Festival, as well as the British Independent Film Award, even though he was competing against one of the actors that would eventually score an Oscar nomination instead of him – Gary Oldman in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. The other members of AMPAS' golden quintet were Jean Dujardin in The Artist, Brad Pitt in Moneyball, Demián Bichir in A Better Life, and George Clooney in The Descendants. Fassbender outperforms them all as far as I'm concerned.

Shame is available to stream on HBO Max.