"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber. (Click on the images for magnified detail)

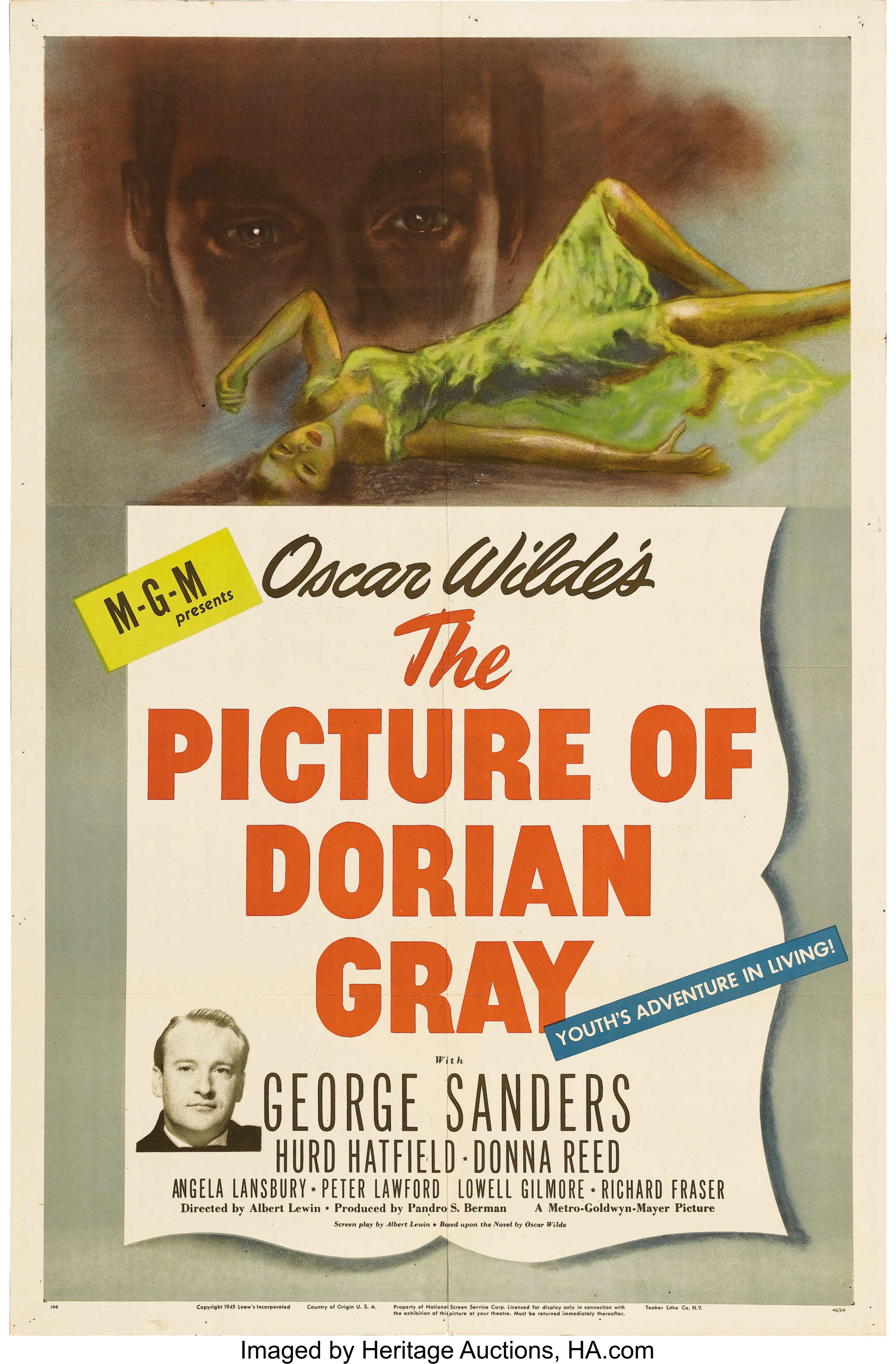

Watching The Picture of Dorian Gray as a horror film in this, its 75th anniversary year, is a bit of a puzzle. It’s almost unrecognizable within the genre, though director Albert Lewin does treat the revelation of the deformed painting itself as something of a jump scare. But the overall vibe is more akin to a period drama or a film noir than anything we would consider spooky today.

Watching The Picture of Dorian Gray as a horror film in this, its 75th anniversary year, is a bit of a puzzle. It’s almost unrecognizable within the genre, though director Albert Lewin does treat the revelation of the deformed painting itself as something of a jump scare. But the overall vibe is more akin to a period drama or a film noir than anything we would consider spooky today.

That is, until you think about it a little more closely.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is an atmospheric horror film about things that don’t necessarily scare us nearly as much anymore: arrogance, beauty and the simple fact of sexuality. In this way it does actually resemble the great horror films of its time, monster movies that make much out of giant laboratories and cavernous castles, unnerving the audience through the use of production design. Dorian Gray’s home is of a piece with Dracula’s castle and the Mummy’s tomb...

There seems to be an understanding, even, that the public’s fears will be triggered simply by exposure to the milieu of Oscar Wilde. And this is certainly an era in which visual suggestion was treated as a kind of psychological magic. Look no further than the other Oscar-nominated films of 1945, from the blunt renderings of trauma and Freudian complexes in Love Letters and Leave Her to Heaven to the flamboyant use of design cues and dreamscapes in Spellbound. The only leap made by The Picture of Dorian Gray is that its architectural language will spook its audience more than its characters.

We actually spend very little time in the palatial townhouse in the early parts of the film. Dorian (Hurd Hatfield) is mostly out and about, either with the caddish Lord Henry (George Sanders) or swooning at nightclub singer Sibyl Vane (Angela Lansbury). It’s not until after Dorian takes Henry’s advice and cruelly tests Sibyl’s morality, that we really settle into the classical opulence of his home. Sibyl’s shadow hovers over the crisp marble floor, floating between dignity and death.

With Sibyl gone, Dorian spends nearly all of his time at home. He wanders the halls and climbs the stairs mostly alone, not unlike Dracula. The ceilings are high and his secret room is way at the top, where he hides his legendary portrait (which I will not be putting in this column, because it’s one of the few details of a film from the 1940s that I think shouldn’t be spoiled).

The style is a bit neoclassical, a bit Egyptian revival, and much brighter than the dank abodes of the Universal monsters. But it induces a different sort of anxiety. A gay anxiety. There’s classical sculpture everywhere, divinely muscular youths and fantastical animals. There’s even a little pond in the back, sporting a decorative column with a very unhappy bust at the top - a herm that won’t get censored.

And then there’s the Orientalist use of Egyptian art, most notably the cat sculpture that winds up in Dorian’s portrait. It’s another way of telegraphing Wilde’s transgressive sexuality, and to participate in a centuries-long use of the generic “East” to represent mystery and the unknown.

But it’s not just the cats. Dorian throws a party, inviting people over to watch an Indian dance performance. The use of design crosses over into spectacle, representing the Victorian fascination with viewing and objectifying colonized cultures, and then associating them with transgressive behavior more broadly. What is interesting is that this representation doesn’t seem particularly critical, despite the film being made decades after Wilde’s death. It is simultaneously a tribute to Wilde and a willing participant in the Victorian moral panic that destroyed him.

I think there might be a temptation to look back on The Picture of Dorian Gray only as a gorgeous, bizarre adaptation of a novel that remains beloved today. Which is fair! But it’s also a relic of a time that was much less kind to Wilde and what he represented. It’s a horror movie in which the monster is both cruelty and transgressive sexuality, even if it only suggests the latter. Hatfield certainly thought so. He credited this film with prematurely ending his career as a leading man, tainting him with its “decadence, hints of bisexuality and so on.”

Of course, it’s hardly as if The Picture of Dorian Gray was the last film to use vague notions of transgressive sexuality as a scare tactic. It’s an early example of a deep tradition, one which developed alongside shifting horror techniques. And perhaps it raises another question: which horror films of today will lose their potency in the future, as the fears the play on slowly dissipate?