For the past few weeks, I've been exploring the greatness of costume design in the realm of horror cinema. None of the movies we discussed, not even those somewhat embraced in the awards circuit, got many golden laurels for their feats of costuming. That's, unfortunately, what usually happens to cinematic excellence that happens to manifest outside the boundaries of prestige drama. However, there are always a few exceptions that prove the rule. Such is the case of Francis Ford Coppola's 1992 adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula. The picture won three Academy Awards, including the prize for Best Costume Design.

The creations of the late Eiko Ishioka are some of the weirdest and most spellbinding costumes ever made for cinema and, as far as I'm concerned, she's the greatest recipient of my favorite Oscar. Michael has recently explored his first foray into the dark marvels of Dracula, and Jason has previously explored Eiko's Oscar win. Nonetheless, I couldn't let Halloween go by without revisiting this most wondrous of big-screen wardrobes. Join me on this deep dive into the nightmarish fantasy of Eiko Ishioka's Dracula…

To understand how all this sartorial splendor came to be, one needs to investigate the collaboration of Coppola and Ishioka, how the director came to work with the designer, and their symbiotic methods of filmmaking. Way before the Japanese artist had ever tried her hand at dramatic costuming, she was an accomplished designer whose advertising campaigns made her a big name in Japan. Back in 1979, Eiko Ishioka was in charge of creating a series of illustrated posters for Coppola's Apocalypse Now, marking the first time the two ever crossed paths.

Throughout the 80s, their creative union would further interlace and fortify. First, she was one of the production designers of Paul Schrader's Mishima, a flick produced by Coppola. Later, Ishioka would design a book about the making of Apocalypse Now and also worked with the director on an episode of the Faerie Tale Theatre. When it came time for Coppola to imagine his version of Bram Stoker's classic tale of blood-sucking noblemen from the East, the director asked Ishioka to create the picture's costumes. One may think that the present version of Coppola's Dracula is strongly defined by its clothing, but this was even more acute in the filmmaker's initial conception of the movie.

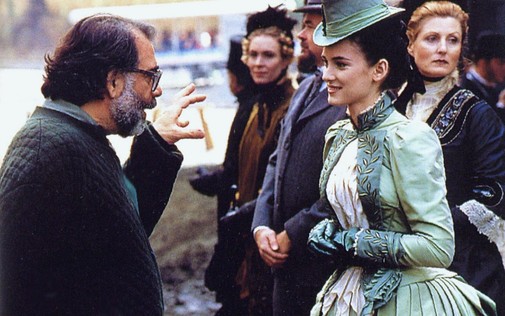

Coppola had a fantastic idea of making the costumes act as sets, twisting the space into such minimalist abstraction that it was the clothes that dominated the image. Studio heads and producers weren't interested in these directorial follies and, in the end, Ishioka's costumes had to coexist with more traditional scenery. Still, it's her designs that control the film's visual language, how the actors move, how the story unfolds. Such artistic liberty is unusual for a costumer, but Coppola trusted Ishioka wholeheartedly.

For instance, normally, a costume designer bends their creations to the logistical demands of the shoot. In Dracula, cinema itself bends for Eiko's creations. The plastic muscle armor that Gary Oldman wears in the picture's prologue, for example, was a holy terror, constantly falling apart and constricting the performance. As for that iconic wedding gown of Lucy Westerna, Sadie Frost was unable to climb into her coffin, forcing Coppola to devise a rewinding shot for the vampire maiden's return to her death bed. These problems metastasized into unexpected blessings, the stilted motion of the actors underlining the grotesque wrongness of the story, the silky opulence painting horror in shades of old gold, ghostly white, and sanguine red.

All this avant-garde experimentation may shape Bram Stoker's Dracula, but Ishioka's designs aren't pure spectacle devoid of deep meaning. Like the genius artist she was, Eiko invoked the epicurean pleasures of looking at lizard-like sculptures of lace and bejeweled robes while also telling a story through her designs. With that in mind, let's look at Dracula's narrative, its characters, and how the costumes illustrate them.

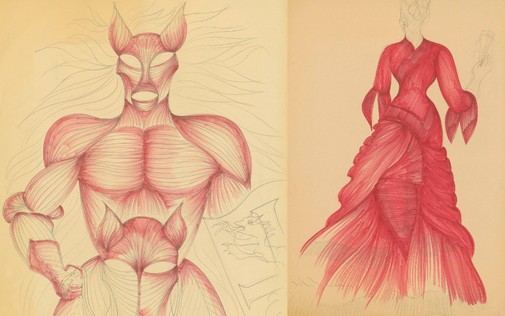

As previously mentioned, Dracula starts with a prologue, a shadow play about the origins of the vampire in the love story of Vlad Dracula and his dear Elisabeta. For this first moment, Vlad's armor is a nightmare of solidified musculature, sinew externalized into a bloody sculpture. He's a flayed man whose insides have turned to an armature, a mix of wolf and human anatomy. In contrast, his suicidal bride is all gold and green, flowering ferns enshrining her body in Slavic symbolism of fertility and sex, lust, and romance. Violence and passion are thus coupled twins in Coppola and Ishioka's movie. When death separates them, all the forces of hell rise to right this wrong.

After these Medieval dreams, the story jumps to 1890s London, where Mina Murray awaits news from her fiancée, Jonathan Harker. He's gone to Eastern Europe to finish the business dealings started by his colleague, Renfield, who's gone mad. Mina is the reincarnation of Elisabeta, the fern-like designs of her costumes and minty color palette making her the modern echo of a past tragedy. However, there's little of the Slavic princess' romance in Mina's figure, so bound is she by the constraints of Victorian propriety. Her bustle gowns are her shackles, cages that barely contain her desires and try covering them with a mask of teacherly sternness.

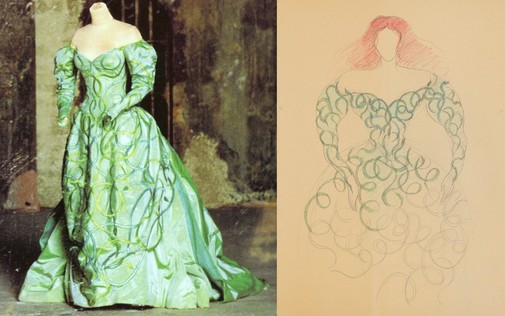

Eiko's costumes have little to do with real History, though they recall the plasticity of the period's art forms. Mina's best friend, the aforementioned Lucy Westerna, may not look like an 1890s aristocrat, but her appearance is that of a Pre-Raphaelite painting come to life. She parades herself in off-the-shoulder pieces of draped sheer fabric, a siren unashamed of her sexuality or her innocence. At a party, she even dresses in snakes, Eve's temptation manifest in embroidery. Such a bohemian flower is bound to be trampled on, whether by the heavy foot of Victorian repression or the abuse of the vampiric count.

Speaking of which, while Mina and Lucy galivant through their English manors and London streets, Jonathan meets the titular monster in the Carpathian Mountains. Eiko, who'd never seen a vampire flick before working for Coppola, imagined Dracula as a demon with many faces, endlessly transforming into new fascinating shapes. Forever changing, forever mutable, he's East meets West, as willfully mysterious as he is enticing. Neither man nor woman, beast or person, old or young, Gary Oldman enters the scene dressed as a giant slash of blood.

Well, before we ever see the count proper, Oldman plays the armadillo-like coachman that takes Jonathan to Dracula's castle. When the English gentleman arrives at the count's abode, he's introduced to the scary scarlet shadow of a Kabuki vampire, part Chinese emperor in silky robes, part Satanic priest in draconic heraldry. While that may be the most famous incarnation of Eiko's Dracula, it's far from being the only one. When Dracula travels to London in his pursuit of Mina, his haggard old age morphs into romantic youth, red vestments giving way to a spectral gray morning suit, perfect for seducing and devouring.

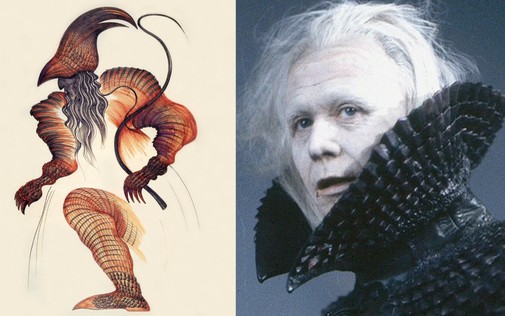

Like a magical infection, Dracula spreads his diseased influence to all those who meet him. Lucy, victimized by his bite, discombobulates in paroxysms of transparent organza, orange wings flying in the night sky, and wanton nakedness writhing in bed. As for Mina, the Victorian cage starts to crumble, her forbidden desires taking precedence over reason. The red bustle gown Winona Ryder wears when Mina has dinner with Dracula is an explosion of lust, passion solidified by tumescent silk. This is a vision of romance looked at through a cloud of absinthe induced inebriation, or perhaps LSD laced mythology. Whatever it is, it's glorious.

As Dracula neglects his victims and Mina escapes to the continent, Lucy succumbs to her blood-sucking malady. When she dies, her three suitors bury her in her wedding gown, a Victorian custom made into Grand Guignol fantasia by Eiko. The designer took inspiration from Australian reptiles with frilled necks and the 17th-century portraits of Michael Conrad Hirt, coming up with the most iconic wedding gown ever captured in celluloid. Pardon my hyperbole, but this is probably my favorite movie costume of all-time, a serpentine curse of lacy ruffs whose beastly inhumaneness terrifies and enthralls in equal measure.

As the story draws to an end, Michael Ballhaus's cinematography grows darker, the spectacular costumes harder to see. Perhaps to compensate for the gloomy bleakness of the lensing, Ishioka dressed Mina and Dracula in costumes that look like they're lit from within for their final scenes. She dons a houppelande-esque gown of velvet lined in silk whose radioactive green shines, a beacon of poisoned rebirth. Dracula, in an ode to his romantic reinvention, ends his existence enrobed in a facsimile of that most love-mad painting, Klimt's The Kiss. The green of silk and the red of blood meet again at the end, golden death emerging as the miracle child of their union. Real death, finite, unlike the vampire's half-life.

All this and there are still mountains of other fascinating costumes we could examine. Tom Waits' Renfield haunts with his disproportionate strait-jacket, hands adorned with mechanical shenanigans that make his extremities look like the metallic brethren of the insects he consumes. Then, there are the Brides of Dracula, ancient ghosts of Greek splendor adorned with Byzantine jewelry, the beads and pearls of their headdress looking like teeth exploded out of a shiny skull. We also have bat-like nuns, a Texan baron's warm fashions, Van Helsing's cartridge pleated cloak, and so much more.

Thanks to Eiko Ishioka's genius and Francis Ford Coppola's imagination, Bram Stoker's Dracula is a visual feast made to be revisited forevermore, each re-watch bound to reveal new marvels hidden within its busy frames. No words of mine can ever summarize the grandness of this miracle of horror costuming, so maddening is its perfection. Kudos to AMPAS for recognizing this cinematic tour-de-force.

More Horror Costuming:

- Us (2019)

- Suspiria (2018)

- Stoker (2013)

- The Skin I Live In (2011)